Toby’s run-up to Brisbane 2032 Olympics starts at unloved Commonwealth Games stadium

The athletes love the old QEII stadium but opinion in Brisbane remains sharply divided over whether it’s the place to run the Olympic athletics in 2032.

Toby Stolberg has a dream. It’s to go for gold in the high jump at the 2032 Olympics – right here in the cavernous Queensland Sport and Athletics Centre arena where she trains on Brisbane’s southside to the thunder of peak-hour traffic.

The lanky teenager has already represented Australia at the under-20 world championships and will be in her prime by the time her hometown Games come around. Her eyes light up when she anticipates what it would be like to compete in them: “Amazing,” she tells The Weekend Australian. “Just amazing.”

Another generation of athletes – contemporaries of the 17-year-old’s grandparents – made this field of dreams their own at the 1982 Commonwealth Games when it went by the name of QEII stadium. As ANZ stadium, it hosted the grand final of a national rugby league competition in 1997; Madonna, U2 and the Matildas have performed at the ageing ground.

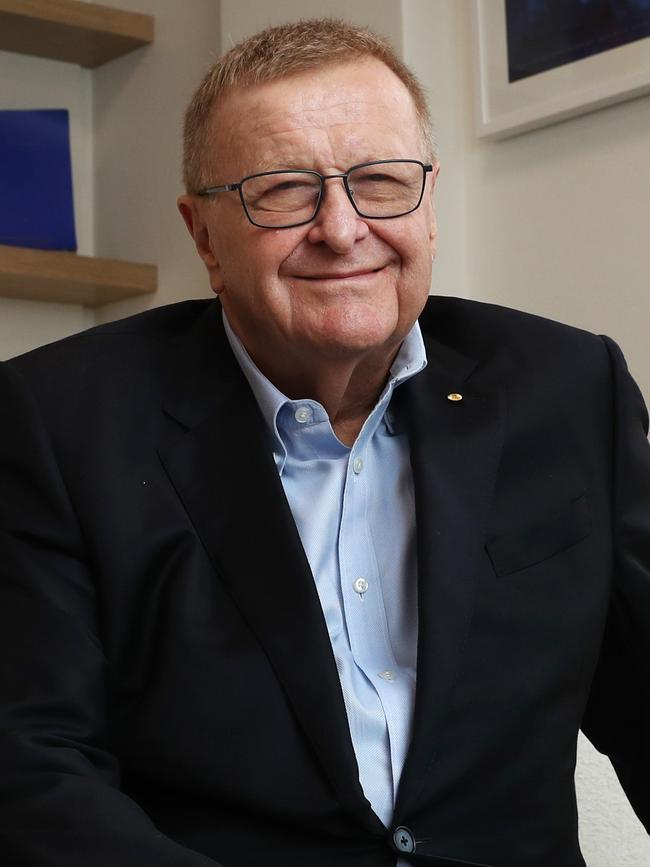

Now, it is to be the focal point of Australia’s third Olympics after Premier Steven Miles rejected the advice of a review he had commissioned into the troubled venues program and plumped for QSAC on the recommendation of International Olympic Committee vice-president John Coates, the man credited with delivering both Sydney 2000 and Brisbane 2032.

Monday’s back-to-the-future decision was received with shock that soon turned to dismay. The stadium is largely unloved by Brisbane sports fans: tucked away in suburban Nathan nearly 3km from a train station, QSAC is notoriously hard to get to. The packed bus from the CBD takes half an hour on a good day, followed by a 10-minute walk. The site is bounded by busy arterial roads on two sides.

Yet the state government will spend up to $1.6bn on new grandstands and temporary seating for a modest forecast capacity of 40,000 when QSAC becomes the main Olympic stadium, and potentially hundreds of millions more to improve the clunky public transport connections.

“It is a total debacle, a tawdry spectacle of egos and political agendas,” complains Campbell Newman, the former LNP premier who also served as Brisbane mayor for nine years.

He got that right. The yawning chasm between what the public was promised from the Olympics and the deeply compromised event that is taking shape burst into full view this week, raising doubt about whether the paradox at the heart of these Games can be reconciled.

They were awarded to Brisbane in 2021 on the contractual basis of the IOC’s no-frills New Norm approach to avert breaking the bank for host cities: the use of existing venues would be prioritised, not shiny new stadiums.

At the same time, the Games were sold at home as a generational opportunity to bring on the infrastructure that the city and its fast-growing hinterland were crying out for.

The sharing of fixtures with the Sunshine Coast and Gold Coast was to pave the way for long-awaited rail and motorway upgrades. The Gabba stadium in central Brisbane would be rebuilt at a cost of $1bn – quickly to blow out to $2.7bn – to anchor an urban regeneration program and leverage the $6.3bn-plus Cross River Rail subway when it opened in 2026.

The $2.5bn-plus Brisbane Arena above Roma St railway station would host the Olympic swimming in a drop-in pool and transform an overlooked corner of the CBD, even though no one could say for sure how much the tricky project might actually cost. In those heady early days, it seemed like money was no object.

And QSAC was on hardly anyone’s radar.

That all changed last month after Coates appeared before the closed-door venues review led by Newman’s successor at city hall, former LNP lord mayor Graham Quirk. The IOC powerbroker did not provide the panel with a written submission. Instead, he talked for three hours, leading to a dispute this week over the message he imparted.

Quirk’s takeout was that Coates was chiefly concerned with the reputational hit the Games were taking in the fierce debate over the cost of the Gabba which, with Brisbane Arena, consumed nearly three-quarters of the $7.1bn in venues funding agreed between the state and federal governments.

Quirk’s recollection was that QSAC was mentioned only in passing by Coates, if at all. He found it “odd” when Coates came out in The Courier-Mail on February 8 calling for the Gabba redevelopment to be axed, the athletics moved out to Nathan and for the Games’ opening and closing ceremonies to be held at the 52,000-seat Suncorp Stadium – the model Miles ultimately adopted.

Coates contests this. He insists QSAC was always in the mix, and he had gone on the record advocating its potential to be repurposed for the Olympics before the review’s instigation. In the event, Quirk’s key recommendation for a new $3.4bn Olympic stadium at Victoria Park on the CBD’s northern fringe hit the deck with a thud.

Miles declared he could not justify the spend in the teeth of a cost-of-living crisis and Coates concurred, telling The Australian’s Jacquelin Magnay that the Olympics’ top brass in Lausanne were unlikely to have agreed to vary the Games delivery contract to accommodate the pricey build.

“The IOC is very sensitive to the cost of the Games and so this approval is not a given,” he said.

Quirk was adamant, however, that refurbishing QSAC at between $1.4bn and $1.6bn was not value for money and “very hard to justify”, especially in terms of what it would deliver in long-term benefit – the vaunted “legacy” dividend of the Games.

Breaking down the required spend, he said replacing the existing grandstands to hold 14,000 people would cost $600m, with capacity added by temporary seating that could be taken away afterwards.

But the “challenging topography” of the hilly site meant a “substantial podium” and other structures for use solely during the Olympics would increase the necessary outlay by between $800m to $1bn, Quirk reported.

His advice to Miles was blunt: “QSAC stadium should not be used as an Olympic and Paralympic Games venue to host the track and field events.”

Olympic greats including champion swimmer Cate Campbell and sprinter Raeline Boyle also came out against QSAC, while 1982 Commonwealth Games star Tracey Wickham told this masthead that Brisbane should hand over the Games to Sydney because the planning was such a shambles. “The legacy will be ‘Australia is pathetic’ if we try to handle this without being ready,” she said.

If Miles’ intention was to clear the air ahead of a state election in October, the plan backfired badly. The three-term Labor government’s standing took another hit on the back of last weekend’s twin by-election debacle where it lost the heartland seat of Ipswich West and recorded a 21 per cent swing against its candidate to replace retired premier Annastacia Palaszczuk in Inala. Newspoll on March 15 had shown that the LNP was on track to win the general election, with leader David Crisafulli convincingly outpointing Miles as preferred premier.

The Courier-Mail went to town on the QSAC call, branding it a $1bn bungle. The story was still on the Brisbane daily’s front page on Friday, a worry for Miles when he would like to move the conversation on. Crisafulli, under pressure from Labor to take a position on the Olympic stadium, finally ruled out any new build, including at Victoria Park. If the LNP prevails on October 26, he will ask the Games infrastructure delivery agency, which Miles is belatedly setting up, to deliver a venue plan within the LNP government’s first 100 days, opening the door to yet another overhaul.

Businessman Steve Wilson, an ex-chair of the state agency that runs Brisbane’s acclaimed Southbank arts and parks precinct who also presented to Quirk, said the QSAC outcome shouldn’t stand.

“I think it’s sensible for whoever is the next government to revisit it after the election, because the case is so compelling to not waste $2bn and rising on a Barnum’s circus – a tent you put up and pull down. That’s not what the people of Queensland, the people of Australia want from the Olympic Games,” he said.

Another former Southbank chair and adviser to the Sydney Olympic Park Authority, urban planner Catherin Bull, cautioned that Brisbane 2032 was in danger of becoming the “make-do Games”.

“How can you commit to Nathan without knowing the critical issues and details?” she said on Friday.

“Accept the reality, take the time to survey and design the precincts and the options for each, test them and then decide. We are still putting the cart before the horse by deciding what to do before adequate testing by design in sufficient detail. This government can’t afford to wait until a contractor is on board with only a vaguely defined scheme if they want to control outcomes and control costs.”

It’s a mess, all right. But Labor wants to turn it into a political virtue with a new social media advertising blitz trumpeting Miles’ move to put “cost-of-living relief over Brisbane stadiums”.

If the attack line has a familiar ring to it, it’s because the ALP trotted out variations of the theme in its successful state election campaigns in South Australia in 2022 and NSW last March, not to mention the flak directed at Liberal Premier Jeremy Rockliff over the proposed $750m-plus Macquarie Point stadium in Hobart in the lead-up to Saturday’s Tasmanian election.

Then there is the other white elephant in the room: the Gabba. Miles kicked that can down the road, though not far. The 128-year-old ground is nearing its expiry date and, by Quirk’s estimate, requires up to $1bn of work merely to be brought up to scratch for disability access and other code requirements. (Women athletes have to use the men’s sheds as there are no dedicated rooms for them.) Even then, he doesn’t foresee the ground’s productive life extending beyond the early 2030s.

Its anchor tenants, Queensland Cricket and the AFL, are relieved not to have to relocate for the five-odd seasons that were to have been taken up by the Olympic rebuild. But where it leaves them in the long-run is anyone’s guess.

Without offering details, Miles has said the savings from axing the full Gabba revamp and shifting Brisbane Arena to a less expensive site will be reinvested in the historic ground as well as rugby league central at Suncorp Stadium. Queensland Cricket chief executive Terry Svenson believes a decision must still be made on the Gabba’s future. Does it stay where it is, hemmed in on a major roads junction that severely limits the development options, or will a replacement site be found after the Games?

“We liked the idea of Victoria Park, but that’s now been ruled out by government and there will be some kind of investment in the Gabba. It allows us not to be displaced and we welcome that,” Svenson said. “But that leaves key questions around the lifespan of the Gabba, and what happens beyond that. I think there’s much more to play out.”

Newly re-elected lord mayor Adrian Schrinner said on Friday that the Gabba could only “limp through” for so long, and Brisbane must have a new stadium, one way or another.

“This is an ongoing need of the community and it’s got nothing to do with the Olympics,” he said before attending a meeting of the Games’ organising committee, OCOG.

Newman, a critic of Quirk’s findings, said he couldn’t understand why the review had gone past the Gabba, despite the stadium’s shortcomings. “If you want to use the Gabba as it is … spend as little as you can to make it as good as it can be for the Olympics. But use it,” he said.

Toby Stolberg is grateful that QSAC is getting some long-overdue attention – for the right reasons, in her view. She’s been training at the stadium since she was 10, and the high-performance facilities at the adjoining Queensland Academy of Sport helped her win gold at last August’s Commonwealth Youth Games in Trinidad and secure eighth place in the high jump at the world under-20s in 2022.

“I don’t know why they would pick anywhere else,” she said. “We already had an amazing track. I just thought it would have been the first place they picked for the Olympics.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout