Brisbane Olympics 2032 plan has divided the state. Can they get it right?

The Brisbane Games offer a chance to rethink the capital’s great sporting venues. But cheap politics and a lack of foresight could see it squandered.

Hopefully – let’s use the word advisedly – former Brisbane lord mayor Graham Quirk will put the show back on track next Monday when he delivers an eagerly awaited report to the state government on Olympic venue development.

As Bull notes, progress seems to have fallen into a hole during the past six months – a “hiatus”, she calls it – that has let the doubt and uncertainty pile up. An urban designer who chaired the agency responsible for Brisbane’s acclaimed South Bank arts and parks precinct and long-time adviser to the Sydney Olympic Park Authority, she has a keen grasp of what is needed to get the city of 2.5 million primed for 2032 and beyond.

What worries her most is what she is not seeing from the powers that be. “All of these unresolved or undiscussed issues have blown up because there is no window in to understand the rationale behind the various proposals,” Bull tells Inquirer. “Do they look realistic? Do they address what we want them to do not only for the period of the Games but for decades to come? I feel the community isn’t prepared.”

Her concern is widely shared. The sense that the preparations need a reset is pervasive. Big names in business, sport, the arts and civic life have joined Bull in speaking out, alarmed that the vision for the Games has come down to whether to spend $2.7bn-plus on the Gabba stadium or where to house the Olympic swimming, rather than the big picture of creating lasting benefit for the Queensland capital and its booming hinterland.

Quirk was tasked by Queensland Premier Steven Miles to sift through the competing arguments and chart a path forward with the short, sharp 60-day inquiry.

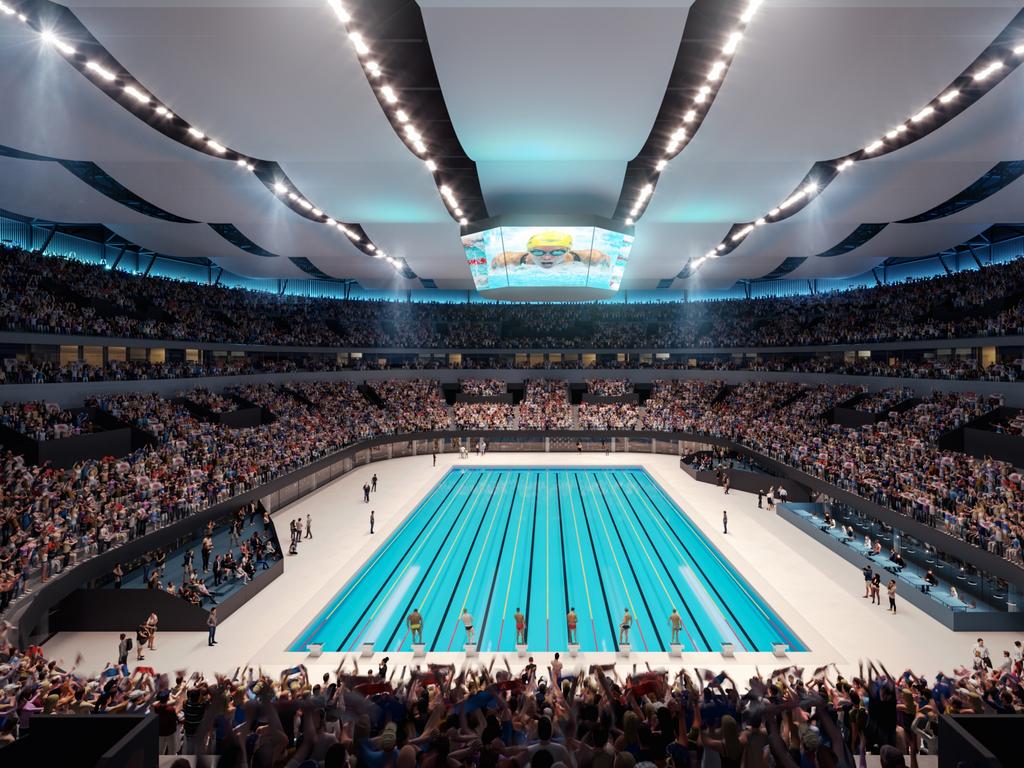

There is little doubt that Miles has gone cold on Gabba 2.0 after the cost blew out from the $1bn first nominated by his predecessor, Annastacia Palaszczuk. Opinion polls show waning public support for the project. Then there’s the $2.5bn Brisbane Arena to be erected above busy Roma Street railway station in the CBD, funded by the federal government and fitted out for the Games with a drop-in pool.

The more potential contractors look at the tricky build, the more sceptical they are that it can be brought in on the capped budget set by Canberra, putting the state on the hook for any over-runs. Before commissioning Quirk, Miles had ordered his department to explore alternative sites.

For better or worse, the two projects anchored the bid Palaszczuk took to the International Olympic Committee to secure the Games in mid-2021, consuming nearly three-quarters of the $7.1bn allocated for venues under a cost-sharing deal she went on to strike with Anthony Albanese. However, they’ve never sat comfortably with the IOC’s New Norm reforms to make hosting the planet’s largest combined-sports tournament more affordable and beneficial. These prioritise the use of existing or temporary competition sites, low-emission outcomes and urban infrastructure that is supposed to create lasting worth for the community, not white elephant edifices.

The regionalised footprint of the Brisbane Olympics dovetailed with an early ambition to link airports in the capital, Sunshine Coast and Gold Coast by heavy rail. What are we hearing now about that useful idea? Crickets. Nearly three years into the Games’ extended “runway”, plans to build or upgrade the required multibillion-dollar rail corridors are still in the planning or approval phases, partially funded and lacking coherence. Long-suffering users of the choked motorways north and south of Brisbane are all too familiar with hours-long delays and snarled traffic.

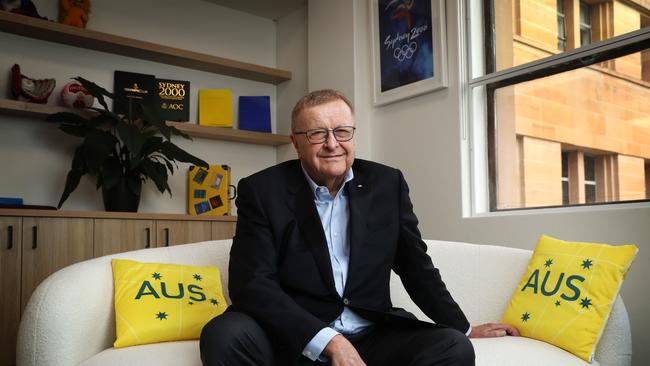

One answer on venues advanced by IOC vice-president John Coates, whose command of the opaque politics of the Olympic movement was key to delivering Sydney 2000 as well as Brisbane 2032, is to dispense with the Gabba rebuild entirely.

Under a proposal he put to Quirk, the centrepiece track and field competition would be run instead at the revamped 1982 Commonwealth Games stadium deep in southside suburbia, with the opening and closing ceremonies held at the 52,000-seat Suncorp Stadium on the western edge of the CBD.

To Coates’s credit, his intervention stirred awareness that there were viable alternatives to the ageing cricket and AFL ground at Woolloongabba. But that misses the wider point Bull seeks to make about the patchwork city. “Brisbane loves doing a bit of bling here and a bit of bling there, but it always forgets the connectivity that is fundamental to making it all work,” she says. “That requires integrated thinking across multiple (government) departments and authorities … and that’s what I am not seeing happening on the Olympics. It’s the biggest challenge we face, and I’d like to see it get a lot more attention and serious thought.”

Take the 1982 Commonwealth Games, often depicted as a “coming of age” event for Brisbane. The then QEII stadium was part of a mixed legacy – underserved by public transport and mostly unloved by the sporting public because of the access issues. When the Brisbane Broncos played there in the 1990s and early 2000s, game attendance plunged 75 per cent.

“I don’t want to bag the joint, but it didn’t work out for the Broncos,” says Bruno Cullen, a former chief executive of the powerhouse NRL club who went on to serve as a director of the Queensland Academy of Sport, now based at the stadium. “If you’re talking about the Olympics it might work – people are willing to cop a bit of inconvenience to get to a big event like that – but … afterwards I’m not so sure. I think you would run into the same issues the Broncos did.”

Business identity Steve Wilson is characteristically blunt: the renamed Queensland Sport and Athletics Centre is a “proven dog” and upgrading it for the Olympics with the combination of new and temporary stands envisaged by Coates would be a waste of time and money. Like Bull, he’s a former chairman of South Bank Corporation and is underwhelmed by the 2032 planning to date: “We need to do better or we’ll look back on this as a lost opportunity.”

In a submission to Quirk, the wealthy stockbroker upended the existing venues model.

The Gabba stadium still would be demolished but replaced by a relocated Brisbane Arena, maintained at 18,000 seats. A new 48,000-seat Olympic stadium would be built at Victoria Park, sandwiched between the northern side of the CBD and the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital campus, within walking distance of two train stations and served by Brisbane City Council’s incoming Metro “road train” system.

Wilson argues the $1bn-plus in anticipated construction savings should be ploughed into upgrading Suncorp Stadium from its current capacity of 52,000 to 65,000 seats, forming a “golden triangle” of interconnected venues framing the inner city. His scheme has certainly stirred the pot.

“Think of what Brisbane might be like after the Games,” he says. “You could have the State of Origin at Suncorp, a full house for the Lions in Victoria Park, Ed Sheeran playing the arena – all on the same night, all within 2km of the GPO. That’s what we have the chance to do here and I don’t want that opportunity squandered by lack of foresight or by doing the Olympics on the cheap.”

Queensland University of Technology chancellor Ann Sherry wants the conversation “lifted up” from the rights and wrongs of the Gabba and Brisbane Arena sites. Miles did the right thing, she says, to reinstate the independent infrastructure delivery agency that was axed by Palaszczuk, who brought the proposed functions inhouse in a controversial move.

“One of the challenges has been that every decision on a venue or funding or some other consideration has been caught up in the day-to-day politics rather than being about the bigger vision for the legacy,” says Sherry, a former chief executive of Bank of Melbourne, Westpac NZ and Carnival Australia cruises who also holds board positions with National Australia Bank and international marketing and communications business Enero Group.

“I … don’t think you want that to come down to a debate about rebuilding a single venue, which is what we’ve basically had up until now. The Olympics are bigger than that.”

The revived co-ordination authority will operate alongside the organising committee of the Games, OCOG, headed by former US-based Dow Chemical boss Andrew Liveris, but as things stand it won’t be up and running until midyear at the earliest.

Liveris’s patience seems to be wearing thin. He chimed in this week, appealing to all sides of politics to embrace the findings of Quirk’s review and get on with the job of building. “We remain concerned with the reduced timelines for venue and infrastructure delivery,” he told The Courier-Mail.

The last thing anyone sensible wants is for the Games to become a political football during a dual-election year in Queensland, kicking off on Saturday with local government voting. The fourth consecutive term for Labor that Miles will seek at the state election in October is a sizable ask by any government, let alone one with the middling record of the outfit he inherited from Palaszczuk last December. Friday’s Newspoll in this masthead shows he faces defeat.

The Greens, meanwhile, have run hard in the Brisbane City Council wards, with their mayoral candidate warning the Olympics will supercharge the property market to make buying or renting a home even more expensive. They want the planned athletes villages to be retained by the state as public housing; the party’s results on Saturday will be watched closely after it surged at the 2022 federal election to snatch two Brisbane-based seats off the Liberal National Party and one from Labor.

Bull warns the “demographic realities” of politics in Queensland will also come into play, when nearly half the population resides outside the state capital. The reasoning goes that nothing infuriates voters more in the far-flung regions than another bucket-load of cash for Brisbane, even if it is for a good cause such as the Olympics.

“There are no urban champions in the government as there would be interstate and there certainly are none visible now,” Bull says. “There is a vacuum at the top, with no one with the experience and, more importantly, the drive to make a great city … and to articulate and defend that process.”

LNP leader David Crisafulli, who heads Miles as preferred premier in Newspoll, a potentially decisive advantage, insists he won’t play politics by mixing his message on the Games – positive for urban consumption, less so beyond the city limits. He was critical when Palaszczuk walked away from the independent infrastructure agency and had pledged to reinstate it in office until Miles beat him to the punch. Too much emphasis has been put on “stadiums and a giant party”, Crisafulli says.

Drawing on his experience with South Bank Corporation, Wilson points to the riverfront precinct as a template for how transformational change can be achieved. The CBD-facing site was cleared of warehouses and crumbling wharves to become the World Expo site in 1988 and preserved as public space afterwards, abutting the international-class Queensland Cultural Centre. “It’s like a string of pearls,” he says, “joined up along the river.”

Wilson trusts that Quirk won’t succumb to pressure to jettison the Gabba site. Regardless of what happens to the stadium, the location is too central and well set-up with its own underground stop on the near-complete $7.1bn-plus Cross River Rail loop to be factored out of the Olympics. Constructing Brisbane Arena there would be less intrusive than the proposed Gabba rebuild and allow Southbank to expand downriver, he says, paving the way for wider urban renewal.

“It’s a case of what’s the best bang for your buck,” Wilson explains. “And my scheme is essentially three venues for the price of two because you save by building the Olympic stadium at a greenfield site at Victoria Park and you save by moving the arena off the railway station at Roma Street. You then use that money to turn Suncorp Stadium into the best rugby league ground in the world at 65,000 seats, which will then attract big acts like Taylor Swift who bypass Brisbane because there is nowhere for them to play.”

Highrise property developer Scott Hutchinson’s personal hate is the 1986-vintage Brisbane Entertainment Centre at distant Boondall, marooned near a northside swamp. A live music buff, he put his money where his mouth was by investing in venues in the Fortitude Valley nightlife district, including the Fortitude Music Hall, which can take up to 3000 standing patrons. He hopes that can be integrated into a night out powered by the Olympics.

“What we don’t want are things like Boondall and Homebush in Sydney where it’s not central,” he says, referring to the 2000 Games HQ. “The Olympics … have to be something we can build on, something we can look back on and remember for all the right reasons.”

Catherin Bull calls it the patchwork city and her hope is the 2032 Olympics will be the thread that finally stitches Brisbane into a coherent whole. This is the ultimate prize, a glittering generational opportunity, but to seize it the Games’ planners and backers must think bigger, be bolder.