‘There can be no doubt of the gravity of the situation’

This decade was a time of fractious debate. Young protesters found lungs on the Vietnam war; a prime minister went missing; and people landed on the moon. We look back at the decade for The Australian’s 60th anniversary.

How do you look back on the biggest news of the 1960s? We share the way The Australian covered three key events on the front page, followed by history editor Alan Howe’s analysis of the decade.

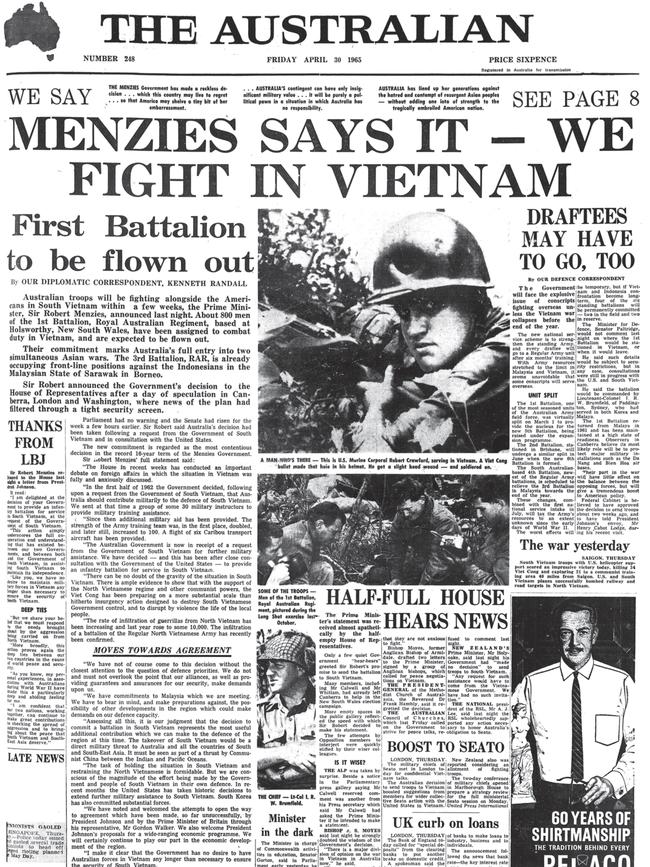

MENZIES SAYS IT: AUSTRALIA FIGHTS IN VIETNAM

- By Kenneth Randall, diplomatic correspondent. First published April 30, 1965

Australian troops will be fighting alongside the Americans in South Vietnam within a few weeks, the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Menzies, announced last night. About 800 men of the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, based at Holsworthy, NSW, have been assigned to combat duty in Vietnam, and are expected to be flown out.

Their commitment marks Australia’s full entry into two simultaneous Asian wars. The 3rd Battalion RAR is already occupying front-line positions against the Indonesians in the Malaysian State of Sarawak in Borneo.

Sir Robert announced the government’s decision to the House of Representatives after a day of speculation. Parliament had no warning and the Senate had risen for the week. Sir Robert said Australia’s decision had been taken following a request from the government of South Vietnam.

The new commitment is regarded as the most contentious decision in the record 16-year term of the Menzies government.

Sir Robert Menzies’ full statement said:

“The House in recent weeks has conducted an important debate on foreign affairs in which the situation in Vietnam was fully and anxiously discussed.

“In the first half of 1962 the government decided, following upon a request from the government of South Vietnam, that Australia should contribute militarily to the defence of South Vietnam. We sent at that time a group of some 30 military instructors to provide military training assistance.

“Since then additional military aid has been provided. The strength of the army training team was, in the first place, doubled, and later still, increased to 100. A flight of six Caribou transport aircraft has been provided.

“The Australian government is now in receipt of a request from the government of South Vietnam for further military assistance. We have decided – and this has been after close consultation with the government of the United States – to provide an infantry battalion for service in South Vietnam.

“There can be no doubt of the gravity of the situation. There is ample evidence to show that with the support of the North Vietnamese regime and other communist powers, the Viet Cong has been preparing on a more substantial scale than hitherto insurgency action designed to destroy South Vietnamese Government control, and to disrupt by violence the life of the local people.”

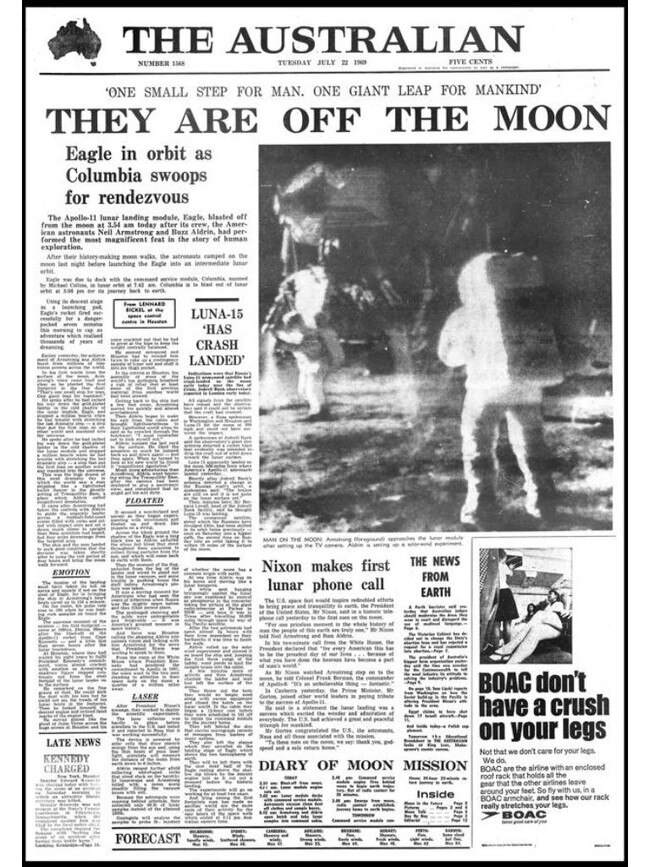

MOON LANDING LEAVES WORLD UNITED IN AWE

- By Kenneth Randall. First published July 22, 1969

Men of science have done their best to explain the significance of what happened on the moon yesterday. But for millions of non-scientists who watched it happening, the event was stunning in its apparent simplicity and matter-of-factness: that, and the fact that they could see it happening.

The Apollo 11 mission has been an incredible feat of technology – greater than any mankind has known before; greater than any he has been capable of performing before.

Dr Wernher von Braun equates man’s first landing on the moon with the moment that aquatic life first crawled on to land. Man was not around to see life emerge from the seas. But the landing and first steps on the moon were shared at the same moment by most of the Earth’s people.

The sense of common involvement and shared experience was unique in man’s history. It seems to stand as a striking irony that the human race had to leave its own planet to create such a moment, yet it is impossible to imagine an earthly event that could so capture the imagination.

The horizons of man can never be quite the same again. The moment may not be recaptured so dramatically until we find a challenge of comparable magnitude to overcome.

On the moon yesterday, the men of Apollo 11 did more to unite the peoples of Earth, even fleetingly, than had ever been done before.

Despite its beginnings in the highly charged air of national competition, the quest for the moon finally transcended the differences between nations. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin reached the goal yesterday, first as representatives of mankind and second as citizens of the US.

“One small step for man – one giant leap for mankind,” as Armstrong put it, with one foot on the Sea of Tranquility. And an intensely personal moment despite the unique coming together of mankind.

Aldrin pointed this out in a simple invitation to everybody, whoever and wherever they might be, “to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours”.

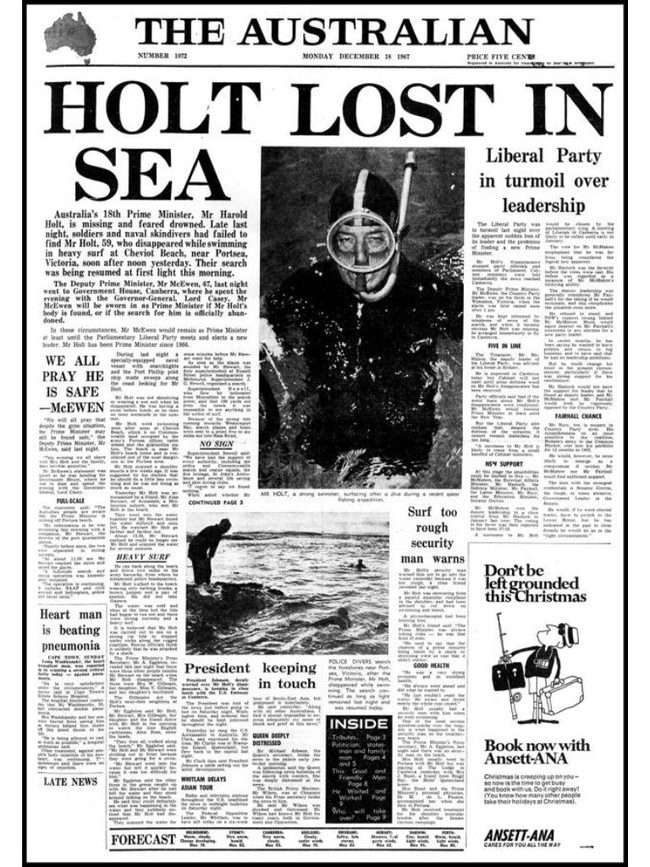

HOLT MISSING, FEARED DROWNED

- First published December 18, 1967

Australia’s 18th Prime Minister, Mr Harold Holt, is missing and feared drowned. Last night, soldiers and naval skindivers had failed to find Mr Holt, 59, who disappeared while swimming in heavy surf at Cheviot Beach, near Portsea, Victoria, soon after noon yesterday. Their search was being resumed at first light this morning.

The Deputy Prime Minister, Mr McEwen, 67, last night went to Government House, Canberra, where he spent the evening with the Governor-General, Lord Casey. Mr McEwen will be sworn in as Prime Minister if Mr Holt’s body is found, or if the search for him is officially abandoned.

In these circumstances, Mr McEwen would remain as Prime Minister at least until the Parliamentary Liberal Party meets and elects a new leader. Mr Holt has been Prime Minister since 1966.

During last night a specially equipped naval vessel with searchlights and the Port Phillip pilot ship made sweeps along the coast looking for Mr Holt.

Mr Holt was not skindiving or wearing a wet suit when he disappeared. He was having a swim before lunch, as he does on most weekends in the summer.

Mr Holt went swimming soon after noon at Cheviot Beach, which is on commonwealth land occupied by the army’s Portsea officer cadet school and the quarantine station. The beach is near Mr Holt’s beach home and is considered one of the most dangerous in the Portsea area. Mr Holt strained a shoulder muscle a few weeks ago. It was suggested by his doctors that he should do a little less swimming and he was not doing as much as usual.

Yesterday Mr Holt was accompanied by a friend, Mr Alan Stewart, of Armadale, a Melbourne suburb, who met Mr Holt at the beach. They went into the water together but Mr Stewart found the water difficult and soon left. He watched Mr Holt go farther and farther out.

About 12.30, Mr Stewart realised he could no longer see Mr Holt and scanned the water for several minutes.

He ran back along the beach and drove two miles to the army barracks, from where he telephoned police headquarters.

It is believed that Mr Holt was carried out to sea on a strong rip tide or trapped under rocks along the rugged coastline. Rescue officials think it unlikely that he was attacked by a shark.

‘RECKLESS WAR’ DEFINES DECADE

- Reflections by Alan Howe, history editor

Robert Menzies’ long, two-part prime ministership was bookended by wars, as was his adult life. He was 20 when World War I broke out, at which point his father was a member of the Victorian Legislative Assembly for a seat in the state’s west. Father and son witnessed the disproportionate sacrifice bush families made over those four years.

Destiny had him as prime minister at the outbreak of the next war, which he grimly announced on September 3, 1939, with the famous words: “Fellow Australians. It is my melancholy duty to inform you … Australia is also at war.”

He believed war was a “failure of the human spirit” and had leant towards an accommodation with Nazi Germany. So it was a surprise when he committed Australian troops to war in Vietnam in a statement to the House of Representatives on April 29, 1965. It was a surprise for the senators whose house had risen – they were headed home. It was also a surprise for Labor leaders Arthur Calwell and his deputy, Gough Whitlam, who’d left early to campaign in the upcoming NSW election. The House was half-full that Thursday evening and there were only modest objections from the thin lines of opposition to Menzies’ unexpected address.

But it started the most fractious, sometimes violent debate of the decade; the Vietnam War would become a lightning rod for controversy as young Australians, slowly at first, would challenge authority across the board, but particularly in response to this war, which would shape the contours of our politics for years.

Quietly, weeks earlier, we had committed to another war – the euphemistically termed Indonesian Confrontation – that to this day remains undeclared, but cost almost 30 young Australian lives. In March 1965, the 3rd Battalion RAR had arrived in Borneo and would, with later deployments, be involved in secret cross-border fighting to suppress Indonesian president Sukarno’s attempt to destabilise the newly formed Malaysian Federation. Much of this would not be reported until 1994.

For many of his opponents, Menzies’ Vietnam commitment made sense of some earlier developments: he had led the 1964 campaign to reintroduce compulsory national service for men aged 20 – an issue that had bitterly divided Australia several times earlier in the century – to help deal with “aggressive communism”. And the Defence Act had recently been amended so that conscripts could be obliged to serve overseas. Later, in 1966, the then minister for the army, future prime minister Malcolm Fraser, outlined the plan to send such conscripts to South Vietnam.

We’d had advisers, experts in jungle warfare, on the ground there since 1962. But in 1965, Menzies told the House that Australia “is now in receipt of a request from the government of South Vietnam for further military assistance”. This was untrue. The then South Vietnamese prime minister, Phan Huy Quat, didn’t want Australian troops and thought it a bad look notwithstanding his beleaguered nation’s hopeless position, even with American help. Years later it was revealed that we asked Phan’s administration to supply such a document retrospectively.

Of the 521 Australians to die in Vietnam, more than 200 were conscripts.

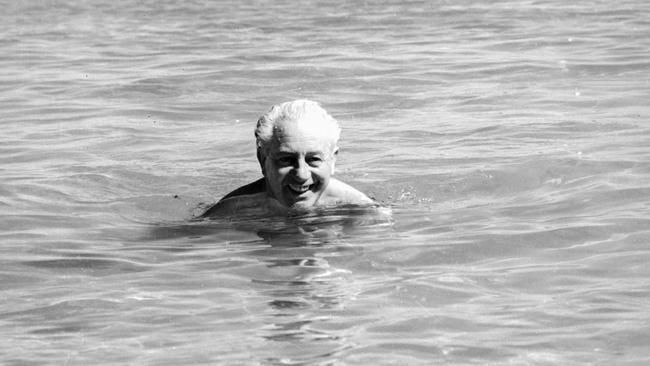

Within a year Menzies would retire, on Australia Day 1966 (the day another event, Adelaide’s missing Beaumont children, also changed our nation) after leading the country for more than 18 years. His successor, the debonair Harold Holt – who the following year would be lost while swimming off Victoria’s Cheviot beach – trounced Labor’s man from the past, Calwell, as Australia’s enthusiastic, war-supporting voters gave the government double the Opposition’s seats at the 1966 election.

But The Australian had doubts about Vietnam from day one and stated that Menzies had made a “reckless decision which this nation may live to regret”.

And we did. In October 1969, Whitlam, campaigning to end our involvement, almost won government.

Our newspaper was born 15 days after the Beatles tour that electrified the country. The times were changing and young Westerners gained a voice, often through music.

At decade’s end, this manifested itself powerfully at 1969’s Woodstock festival – Neil Armstrong had walked on the moon the previous month, the Manson murders were the week before – at which Country Joe McDonald would famously sing: “Well c’mon mothers throughout this land, pack your boys off to Vietnam … be the first one on your block to have your boy come home in a box.”

Weeks later, The Australian’s Douglas Brass put it more eloquently: “How much longer can we Australians stomach this filthy war … How much longer is our glib government going to turn a blind eye to the terrible things that are being done, in this mad crusade, to miserable wretches in primitive villages?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout