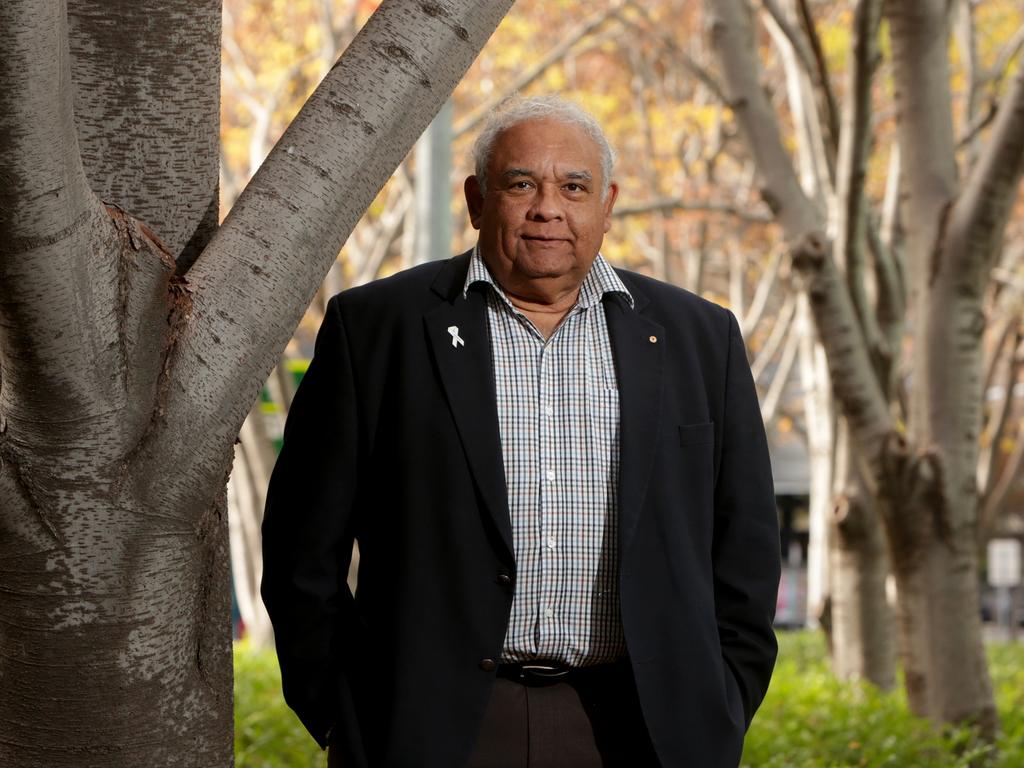

The Voice will be practical as well as symbolic says Tom Calma

Professor Tom Calmer argues the practical benefits of enshrining an Indigenous advisory group such as the voice in the Constitution include long overdue progress in closing the gap in health, education and employment.

The practical benefits of enshrining an Indigenous advisory group such as the voice in the Constitution include long overdue progress in closing the gap in health, education and employment, First Nations Referendum Working Group member Tom Calma has argued.

In an attack on “myths and misinformation” circulating in current debate, Professor Calma rejected the perception that the voice was purely symbolic when he delivered the 2022 Goldring Lecture at the University of Wollongong.

“It is a structural change that will deliver a permanent advisory body on issues affecting First Nations people,” he said.

“[It] is all about advising on how best to improve practical outcomes on the ground, and delivering better outcomes. It is a practical change that will empower First Nations people to advocate for the solutions that they know are effective. No one can deny that real change is needed to close the significant gaps for First Nations people.

“The voice is the change that is needed. It is important for us to support ways for First Nations people to have a say on what matters most to them, including practical action to close the gap.”

Among other negative arguments he attacked was that a voice was not needed because there were 11 First Nations representatives in the parliament; he said they represented constituents and political parties.

He also dismissed the argument that there was not enough detail about the proposal, pointing to published reports and planned civics education and information campaigns.

Professor Calma took aim at social media and “some Indigenous commentators’” claims that not all Indigenous people supported a voice.

“This is true, as there are a wide range of views among First Nations people,” he said. “Just like any group of Australians, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians are diverse and don’t all think the same way.

“However, the voice proposal is the result of successive processes of consultation and engagement – involving thousands of individuals and engaging with communities right across the country. First Nations leaders have been calling for this reform for decades.

“I am confident there is overwhelming support within First Nations communities, which will only continue to grow.”

Professor Calma said official attempts to give Indigenous Australians a voice dated to 1957, with the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines & Torres Strait Islanders, dissolved in 1973 to make way for a succession of such bodies.

The voice was “a once-in-a-generation opportunity to change our Constitution and place our nation on a pathway to a better future”.

The concrete outcomes of establishing a voice were also stressed by another Referendum Working Group member, Noel Pearson, in the first of his Boyer lectures for the ABC on Thursday.

“This constitutional partnership will empower us to work together towards better policies and practical outcomes for Indigenous communities,” Mr Pearson said.

He said the move towards constitutional recognition was “the last leg of a long journey” and that the vote would decide “whether the nation should build its greatest bridge – a bridge to unite at long last the First Peoples of this country with our British institutional inheritance and our multicultural achievement, under the Constitution”.

The federal government has promised a referendum on the voice in the 2023-24 financial year.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout