Hidden memories: Cecil Clarke’s account of the Gallipoli landing

Cecil Clarke kept the remnants of his war in an old biscuit tin, locked in a garden shed beneath an ancient lemon tree.

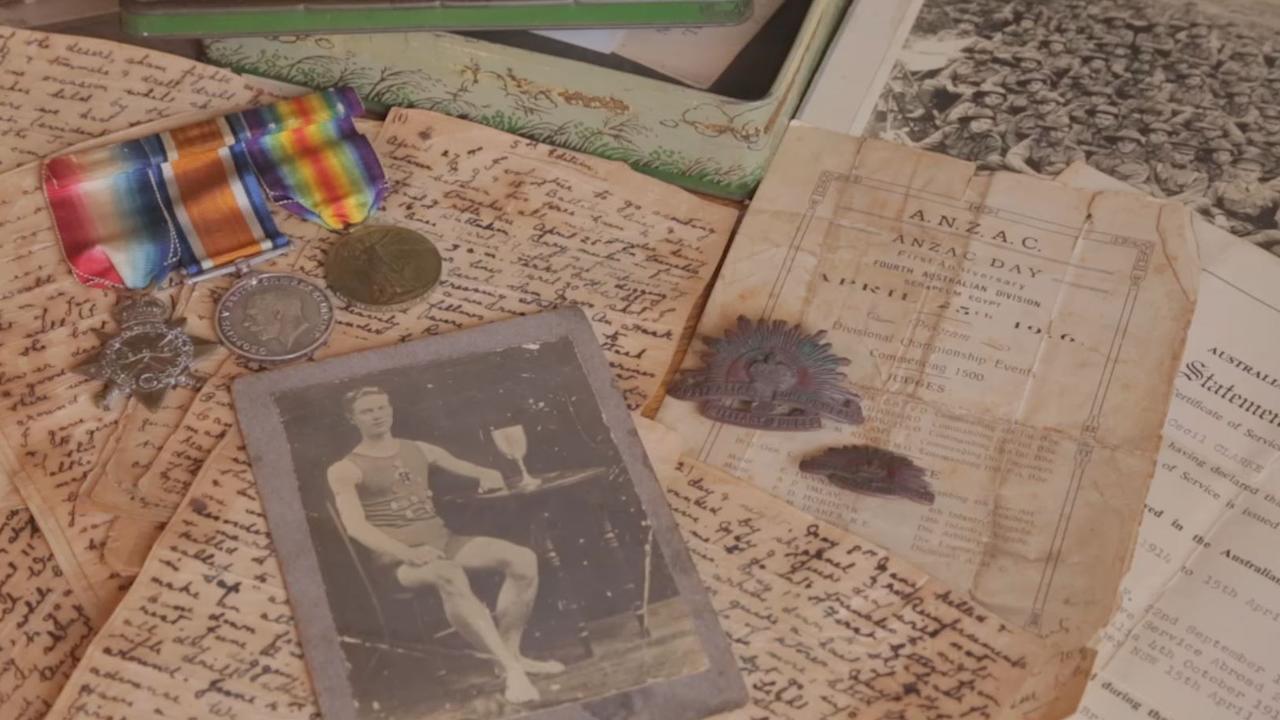

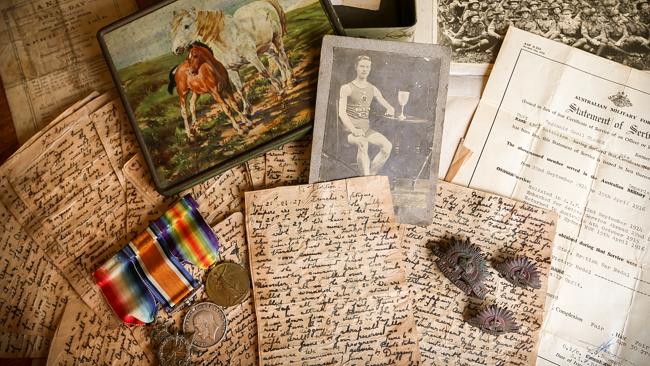

Cecil Clarke kept the remnants of his war in an old biscuit tin, locked within a garden shed beneath an ancient lemon tree. The rising sun badge worn on his slouch hat when he landed at Anzac Cove; a single rifle bullet from among those he fired from the Australian trenches once they were dug in; and the medals he earned for fighting through the months that followed.

His granddaughter, 62-year-old Gwen Chatenay, remembers how, as a child, she tried to force open the shed door despite the chain that kept it closed.

“We knew grandpa’s war things were there,” she says today. “Memories that needed to be kept imprisoned, at a safe distance … away from his wife, children and grandchildren, away from his roses and away from him.”

Clarke barely spoke about the war to his family, she says, and it was only long after he died that they opened the tin, and found the diary that he kept throughout the Gallipoli campaign. Sparse and often brutal in its description, the diary will be presented to the Australian War Memorial. It has never been seen publicly before.

The diary may have been Clarke’s only record of his Gallipoli experience. It looks like it was scribbled in brief notes while in the trenches and later assembled in a series of letters sent to his mother, Agnes. They were written in black ink on coarse, brown, single-sheet aerograms, and after Agnes died, they were sent back to Clarke, who kept them without telling anyone they were there.

“When I think of grandpa, I think of him being two people,” Gwen says. “The grandpa that we know, who loved cricket, who taught me how to prune roses, and then there was the other person. When I think of pictures of him in uniform, I think ‘Who is this person?’ ” Now brittle with age, Clarke’s diary represents a very private answer to her question.

Like many of those who signed up to what became the 13th Battalion, Australian Imperial Force, Reginald Cecil Clarke was not born in Australia. Aged 29 and alone, he took the steamship to Sydney from Liverpool in northern England on September 30, 1912, paying £16 for his one-way ticket. Fair-haired and blue-eyed, Clarke brought with him a reference from his past employer, a printery, which described him as “a most conscientious and reliable workman”. He also carried a handwritten letter from his Methodist minister, paying testament to his “life-long relation to the Sabbath School & Church.”

Less than two years later, Clarke began his short and savage war. On September 22, 1914, eight weeks after the outbreak of World War I, he was one of thousands who hurried through the sandstone gates of Sydney’s Victoria Barracks to volunteer.

The men came from across NSW and, according to a history of the battalion, were the pick of the strongest, healthiest recruits and soon nicknamed the Battalion of Big Men. A champion swimmer, Clarke was a good fit. A photograph of C Company, 13th Battalion, taken at the time shows him sitting cross-legged and confident among his new mates. Others among the photograph’s nine rows of men look particularly young.

Three months to the day after Clarke signed up, on December 22, C Company boarded the Ulysses, a 10,000-ton Blue Funnel liner fitted up to carry troops from Melbourne to the Middle East.

‘‘With the sounds of cheers from shore and strains of martial music from the regimental bands, the lines were ‘let go’ and everyone was merry and bright, with high hopes for the future,” his diary says. He carried a pocket-sized New Testament from his fiancee, Florence, in which she’d written “with a prayer that God will keep you safe and grant you a speedy return”.

Sailing through Christmas, the Ulysses put in at Albany, Western Australia, to join a convoy of ships carrying 10,500 Australian and 2000 New Zealand troops. “The sight of green fields and red tiled houses did one’s eyes good to behold,” Clarke wrote. “From here we lost sight of the coast of Australia, and were bound for some destination, to do ‘our bit’.”

On Sunday, January 31, the convoy reached Alexandria in Egypt. They took a train inland to Heliopolis, near Cairo, then a tired and sea-weak march across the desert to their final training base.

Dead Turks, sailors and soldiers were lying all over the beach.”Reading his diary from this time, you sense Clarke’s wonder at what he saw; he writes at length, often in retrospect, describing the mix of people from “fine men with skin as black as coal” to others “with their white turbans and flowing robes” or red fez hats. He went to Cairo’s mosques, the pyramids and “Luna park, which was only about 15 minutes walk from the camp, a place given over to shows of all kinds”.

Against all this was the constant monotony of training. “Marching through the sands of the desert, sham fights against NZ & Tommies & drill, drill, drill.” On April 11, the soldiers left camp for the final time. Sleeping on iron decks on board their boat, they spent a last few days in lectures and training with their ammunition and their guns.

At 10.30 on the morning of the 25th, they sailed.

From the first day in Gallipoli, the diary’s style changes. Now there are short, hard sentences, written in the present tense. An entire day is often captured in a few words.

C Company landed under fire at 9pm. “Dead Turks, sailors and soldiers were lying all over the beach.” By April 26, “bullets & shrapnel falling like hail digging for very life with entrenching tools.”

The monotony of daily life now is deadly. On April 27: “Digging trenches all night under heavy shrapnel & rifle fire.” April 28: “Bury mules in front of our lines.” On April 30: “Sam Mayo shot, I take him to dressing station.” On May 1: “Men shot all around but so far am uninjured.”

From May to August, the 13th Battalion was caught up digging, then defending the Anzac front line. Deafened for days by an artillery attack that killed several of their officers, Clarke nevertheless went back into the trenches to keep fighting.

In a scrapbook found with his diary after he died, Clarke had collected some of the first newspaper dispatches sent back from Gallipoli to Australia by the official war correspondent, Charles Bean.

In places, the war as he saw it and as told by Bean seem to correspond. On May 19 in Clarke’s diary there is optimism that “things seem to be going alright. Great bombardment by our guns of the Turkish trenches”. On the same day, Bean records how “the Australian seems to be able to turn everything into a laugh.

“As the Turks were bolting back from where they had thrown themselves down in the scrub and grass, someone shouted at them ‘Play you again next Saturday’,” Bean wrote.

In other places, the two men’s war reports diverge. On May 29, under the headline ‘‘Baseless atrocity stories’’, Bean reports how “the conditions of the burial armistice the other day were very honourably observed.” Clarke’s diary also mentions the May 24 armistice, which he says took place only after this: “Turks come out of their trenches with white flags and wanted time to bury dead, but as movement of troops were observed they got bombarded instead.”

Three weeks later Clarke buried the broken body of his mate, George Mosey, who looks like he is trying to suppress a grin in that photograph of C Company taken before they deployed. It’s as if the grief has left him without words: “Buried Mosey & another at Cemetry,” his diary simply says.

Lieut. Sinclair killed by a bomb in trench. Corporal in charge shot through the head. I take charge.”Yet, even in his diary’s most stunted, bare sentences, there is ample evidence of heroism. Clarke was a lance corporal — the army’s most junior rank but one — when, in early August, “Lieut. Sinclair killed by a bomb in trench. Corporal in charge shot through the head. I take charge.” He and his men fought without water for almost 58 hours.

Then, on August 10, Clarke was “wounded by a bomb about 5am”. The diary doesn’t mention it, but the blast blew out his eye.

Taken back to the beach where he’d landed, Clarke lay there all day and through the night. The next entry, on August 11, reads “Still waiting on the beach. Wounded men shot by my side, while lying on stretchers waiting to go aboard Hospital ship. Plenty shrapnel & bullets flying round”.

The power of this account is simple; a century after the battle they describe, no one apart from Clarke’s closest relatives had read a word of it.

Clarke left Gallipoli on August 12. The bomb that took out his eye also shattered the roof of his mouth and left him with blurred vision and defective hearing. After weeks in hospital, he made it back to Sydney in October and married Florence within months. In their wedding photograph, you can clearly see the broken skin and bone around his glass eye.

Unable to fight on, Clarke was discharged in April 1916. Among other possessions found after he died is a printed notice from that month, advertising the first anniversary commemoration of the landing held by his comrades, who by then were back in Egypt. On the reverse of is a handwritten letter sent to Clarke which read, “by the time you get this, we expect to be in Europe”.

The 13th Battalion went on to fight its way across France and Belgium, at the Somme and Flanders, Ypres and Passchendaele. In February 1917, Captain Henry William Murray, who had been at Gallipoli on that first day, was awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest honour the Australian military can bestow.

At the battle of Amiens, in northern France on August 8, 1918, the 13th were part of what German General Erich Ludendorff called “the black day of the German Army in this war.”

Looking back, from the landing at Gallipoli through each of the bloody years that followed, Clarke’s battalion of volunteers was at the heart of what has become Anzac legend today. They became known as The Fighting Thirteenth.

Writing about Anzac Day, military analyst James Brown, who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, says war is not black and white but “all too many shades of grey”.

On his return to Sydney, Clarke was sent to hospital in Randwick, where the last line of this diary says he “passed Dr. & came home”. What he only later told his wife was that, outside the hospital, a woman walked up and gave him a white feather. As he was dressed in a civilian suit, she assumed he had not been to war and wanted to brand him publicly as a coward.

Like many of those who came home from the Great War, Clarke struggled to find work. There were few jobs going for a one-eyed printer. He did what he could, raising a family in Bexley, close to the grazing land that would become Sydney Airport. He was known as a gentleman who would tip his hat to women as they walked down the street.

He kept the biscuit tin containing the fragments of his war in the garden shed of the Bexley home.

“I’m amazed by the fact he could put everything in a box, close that box like turning a page in a book and put it away,” says his son Keith. Towards the end of his life, however, Keith does remember his father having nightmares. Clarke would try to push Florence into a cupboard, or under the bed, to hide her from the imagined, onrushing Turkish troops.

Clarke’s grandchildren remember him “whittled away” with age, still carrying the scars on his chest and back from the barbed wire he struggled through on his way up from the beach and among the trenches at Gallipoli. Doctors were unable to remove all the shrapnel from the bomb that took out his eye. Into his 80s, these twists of metal trapped inside Clarke’s face would continue to force their way out, often when he ate. On their regular Sunday afternoon visits, his grandchildren would sit fascinated while he stood, walked to the bathroom and returned with another fragment that had worked its way through his flesh. Clarke never complained.

Keith, now 88, was too young to be called up in 1939, but says having fought the war to end all wars, his father was “horrified, absolutely” when World War II broke out.

Years later, Keith’s son Bruce became a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War. Bruce, appearing live on national television, challenged the then attorney-general Ivor Greenwood to arrest him, with his unsuspecting family watching at home. Clarke did not criticise his grandson. One of the few things his family remember him ever saying about Gallipoli was “there’s no glory in war”.

Throughout his life, the biscuit tin came out only once a year, on April 24, when Clarke polished his medals for the day ahead. He never missed a march. Anzac Day for Clarke was about respect for the people he’d served alongside. No two-up games, no drinking, just rosemary and a long walk. He died in 1972, aged 89.

After his death, some of Clarke’s papers were bundled up and given to Bruce who, by then, was working as a lawyer in central Sydney. They lay unread for years. When he finally opened the bundles and copied the aerograms, he realised they explained so much of what he had never asked his grandfather while he was alive. Carrying the diary, Bruce travelled with his father and his son to Gallipoli to retrace his grandfather’s campaign.

“It staggered me. We walked down and touched the water,” Bruce says.

His son picked up a pebble from the beach and took it home. They struggled up the steep, uncertain hillsides to where Clarke and his fellow troops dug trenches, which can still be seen today, carved into the crumbling earth.

“Their trench was there and the Turks’ trench was as close as the washing line,” Bruce says, looking out into the garden of his parent’s home. “A five-year old could stand up and throw a cricket ball …” he trails off.

It was Bruce’s decision to commit his grandfather’s diary and papers to the War Memorial, unsure of his own ability to preserve almost century-old documents. They are also not entirely his, he says, but “part of a greater collective history” of Australia itself.

At its most personal, the diary is “a recognition of a couple of people that … should be remembered”, Bruce says. George Mosey, whom his grandfather buried. Lieutenant Hubert Hartnell-Sinclair, who was killed, leaving Clarke in charge.

“I wonder if the relatives of Mosey or Sinclair were ever aware that he documented the end of their lives,” Bruce says. “Because people coming back from the war just didn’t talk.”