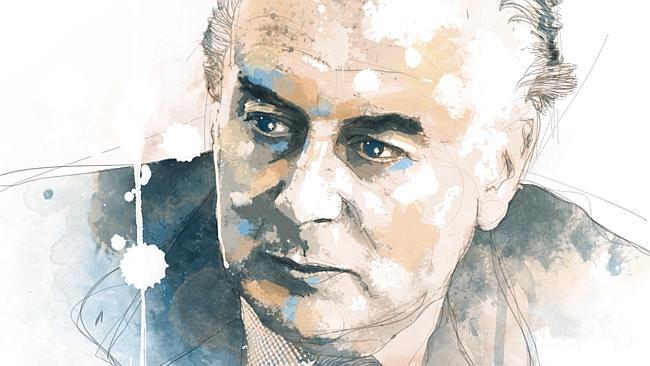

Gough Whitlam’s long and fortunate life

Australia has seen better prime ministers than Gough Whitlam but few who have made a bigger impact on political and public life.

Labor prime minister 1972-75. Born Melbourne July 11, 1916. Died Sydney October 21, 2014, aged 98.

His government flashed across the political sky like a meteor, soaring to dizzy heights before crashing to earth in an even more dazzling shower of sparks.

It lasted just three years and 11 days but it became a reference point in Australian politics for much to be admired and emulated, at least by Labor supporters, and a great deal to be condemned and avoided. The frenzy of decisions it unleashed after 23 years out of power changed the nation, in some areas permanently.

Whitlam himself brought stature, distinction and brilliance to the leadership, together with wit. Hawke government minister Barry Cohen asked him on one occasion how he might react when he met his maker. “You can be certain of one thing,” Whitlam responded, “I shall treat him as an equal.” That was typical of a humour, which, like much of the rest of his style and behaviour, inspired loathing and deep affection in roughly equal proportions. If to many it was a sign of his arrogance, to others, including those who knew him, it epitomised his fondness for sending himself up.

His speechwriter and biographer Graham Freudenberg characterised the Whitlam style as “a certain grandeur”. His relatively brief period holding the reins of power contrasted with decades dedicated to public life, from the time he entered parliament in 1952 to his death. It was reflected in the title of his last book on public policy, published in 1997 – Abiding Interests.

Before 1975, Whitlam could have expected to be remembered mainly for bringing Labor to power for the first time in 23 years, for a series of significant achievements in foreign and domestic policy and for fostering a new sense of national identity, together with presiding over a disastrous economic policy. Instead, his great moment in history came with his dismissal on November 11, 1975 by governor-general John Kerr, creating Australia’s greatest political controversy.

Although not acknowledged by Labor partisans at the time, there is no doubt that Kerr, appointed by Whitlam only a year earlier, acted within his legal rights under the reserve powers of the constitution to resolve a deadlock between an opposition that refused to pass the budget through the Senate and a government that refused to call an election. It is just that few imagined the powers would ever be used by the Queen’s representative to strike down an elected government. The only precedent in Australia was the dismissal of NSW premier Jack Lang by governor Phillip Game 45 years earlier.

Kerr’s action damaged the fabric of Australian politics, leaving the government headed by Malcolm Fraser handicapped, despite its landslide victory in 1975.

The criticism of Kerr that endured was that he deceived the prime minister, giving him no indication of his intentions for fear that he would be dismissed himself by the Queen on Whitlam’s recommendation. Arguably, the situation could have been resolved politically, whether by wavering Coalition senators passing the budget, by the outcome of the half-Senate election, which Whitlam intended to call on the day of his dismissal, or by being given the choice of calling a general election rather than suffering the ignominy of dismissal or of any attempt to sack the governor-general and replace him with a more compliant vice-regal representative.

Kerr’s action damaged the fabric of Australian politics, leaving the government headed by Malcolm Fraser handicapped, despite its landslide victory in 1975. The best authority for this assertion is John Howard, who wrote in 1990 on the 15th anniversary of the dismissal that the Coalition’s decision to block the budget “with hindsight perhaps ... had an impact on the perceived legitimacy of the government. I think it affected psychologically the way the government behaved.”

But some of the more dire predictions at the time of the dismissal were not borne out. It did not alienate the Labor party from parliamentary democracy; To the contrary, it returned to office eight years later for the longest federal term in its history. And in perhaps the ultimate irony, it appointed former republican and Labor leader Bill Hayden as governor-general. The consolation that Labor supporters drew from the dismissal – that it would hasten an Australian republic – also proved to be misplaced, with divisions amongst republicans defeating the referendum held in 1999.

Edward Gough Whitlam was born in the Melbourne suburb of Kew into what was to become an upper-middle class home. His father Fred was a public servant in Melbourne and Sydney before moving when Gough was 12 to the newly established national capital. By then, his father was deputy crown solicitor under Robert Garran and was later to become solicitor-general. In Sydney, Gough was a pupil at Knox Grammar and in Canberra, at Telopea Park High, a government school, and Canberra Grammar. He went to Sydney for a law degree, enlisted in the RAAF in 1941, serving as a navigator on bomber aircraft and the following year married Margaret Dovey, a champion swimmer and daughter of a leading barrister who was to become a judge.

He joined the Australian Labor Party while still in uniform in 1945 and seven years later won the Sydney western suburbs seat of Werriwa in a by-election. Whitlam’s background was not classically Labor, in the sense that he had engaged in manual work or become a trade union official. He was at the vanguard of a transformation of the ALP from the party of the cloth cap to the mortar board and the barrister’s wig. His background growing up in a public service family in Canberra shaped his political orientation.

Freudenberg wrote: “He took certain propositions as self-evident and among these were: that the national parliament was the only really important parliament in Australia; that the role of government was constructive, positive and benevolent; that action by governments, through parliament and the public service, was the normal and natural approach for the solution of Australian problems...” In other words, he saw government in a traditional Labor way – as an instrument for the improvement of the lot of Australians.

As a lawyer and believer in the role of government, he pursued constitutional reform and a re-ordering of the functions of the states and the federal government. His electorate of Werriwa, in southwest Sydney, confronted him with the deficiencies of life in the outer suburbs, which led in office to a program of commonwealth grants to the states for education, health, transport, housing and urban improvement.

The traditional Labor catchcry of equality through redistribution of income became one of equality of opportunity, through services provided by the community.

As former NSW premier Neville Wran once put it: “It was said of Caesar Augustus that he found Rome of brick and left it of marble and it can be said of Gough Whitlam that he found the outer suburbs unsewered in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane and he left them fully flushed.”

In 1960, eight years after coming into the House of Representatives, Whitlam, aged 43, became deputy Labor leader under Arthur Calwell. The contrast was immediately obvious between the tough, gruff and electorally unappealing Calwell and the urbane, articulate Whitlam.

Yet Calwell came within one seat of winning the 1961 election in the wake of the credit squeeze imposed by the Menzies government. It was, however, the only time he looked electable. Whitlam had to wait until Labor had suffered another two election defeats, in 1963 and 1966, the second a landslide loss over Calwell’s passionate opposition to what was then a popular war in Vietnam.

By the time he became leader, the Whitlam style was becoming established: a self-confidence which sometimes tipped over into arrogance in his dealings with opponents inside and outside the ALP. “You either crash through or you crash,” was how he put it. He fought pitched internal battles in support of state aid for private schools and for reform of the party structure.

He used his facility with words like a rapier. Parliament was his stage, employing logic, wit and a touch of the theatrical to establish his dominance over successive prime ministers – Harold Holt, John Gorton and William McMahon. He parodied Gorton’s convoluted speaking style and ridiculed McMahon as “Tiberius with a telephone”, over the way he handled a political crisis.

His cleverness with language sometimes went too far for his own good. Referring to a description of the Labor Party’s federal conference, which formally determined party policy, as “the 36 faceless men”, Whitlam said of the ALP’s federal executive:

“I can only say we’ve just got rid of the 36 faceless men stigma to be faced with the 12 witless men.”

He came within an ace of expulsion from the party in 1966 over his support of state aid and in 1968 he resigned after being rolled by the federal executive, winning the subsequent leadership contest against Jim Cairns by only six votes. But Whitlam drove on to prepare the party for government, including through federal intervention to force a restructuring of the Victorian ALP, for years a deadweight in the party’s effort to win seats.

The 1969 election saw Labor gain a 7 per cent swing, the largest shift in votes since 1943, and win 18 seats to shrink the Gorton government’s majority to seven. Coming at a time of economic prosperity, it created a perception of irresistible momentum.

McMahon replaced Gorton as prime minister, tilting the scales further to Labor by pitting a political pygmy and figure of fun against a colossus. World events also played in Labor’s favour, with mounting opposition to the war in Vietnam and moves to end the isolation of China. Whitlam visited China in 1971 and was granted an audience with Premier Zhou En-lai.

McMahon’s attempt to exploit the visit by harnessing Australian fears of China backfired spectacularly when US president Richard Nixon announced two days after Whitlam left Beijing that he would be visiting China himself.

When McMahon finally announced the election for December 2, 1972, Labor’s slogan captured the mood of the nation precisely – “It’s Time”. For all the dominance of Whitlam over McMahon, the six years of strategic planning and policy preparation by Labor, the strongest sentiment was that the Liberals had been in power too long. Overlooked in the euphoria of victory after 23 years out of office was that Labor gained a swing after preferences of only 2.5 per cent and eight seats. This gave it a majority of nine – a substantial way short of a landslide.

Impatient to start governing and frustrated with an electoral process that would delay a meeting of the Labor caucus and therefore the election of the ministry for two weeks, Whitlam arranged for himself and deputy Lance Barnard to be sworn into the existing 27 portfolios. What followed was a flurry of decision-making that left no doubt that Australia had a new and different government.

The announcements included the withdrawal of the remaining troops from Vietnam, an end to military conscription and the release from jail of conscientious objectors to conscription, diplomatic recognition of China, abolition of knighthoods, support for equal pay for women, removal of the sales tax on contraceptives, the first moves towards Aboriginal land rights and a ban on racially selected sporting teams from South Africa.

Whitlam interpreted the mandate of voters literally by setting out to implement line by line the Labor platform, which he had largely re-written and which in large part he had reproduced in his 42-page policy speech. Believing education to be the key to equality of opportunity, the government abolished tertiary fees and greatly increased spending on schools, universities and colleges. Pensions were increased and indexed and Medibank established as Australia’s first national health insurance system. There was a major expansion of commonwealth programs in areas such as urban and regional development.

A more independent foreign policy, promotion of the arts, including through the establishment of an independent Australia Council and of the National Gallery in Canberra, an Australian honours system and the abolition of appeals from the High Court to the Privy Council created a new sense of Australian identity. Papua New Guinea was granted independence. The Family Law Act made divorce easier to obtain and the Racial Discrimination Act codified a new area of the law. At least at the start, it was a period of rare idealism in Australian politics, when Australians dared to dream that a government could build a better nation.

Of course, much of it cost money and some of it a great deal. Federal government spending increased by 3.8 per cent after inflation in 1973-74, 15.8 per cent the following year and 12.8 per cent the next. Whitlam in opposition had argued his program would be financed through economic growth and the resulting rise in revenues and there were few at the time who questioned the assumption.

Indeed, it may have been valid if Labor had been elected in 1969, with the next three years continuing the seemingly unending cycle of growth. But the first OPEC shock, with its quadrupling of oil prices, ushered in a new world – one to which all governments had difficulty adjusting but the Whitlam government more than most. While real revenue growth of 10.4 per cent in 1973-74 more than matched growth in spending, the 5.8 per cent and 3.6 per cent in the following two years fell far behind, creating ballooning budget deficits.

Whitlam himself had never shown much interest in economic policy, mainly because he saw no need to.

Whitlam himself had never shown much interest in economic policy, mainly because he saw no need to. As he wrote in The Whitlam Government: “During the years of the post-war economic boom, questions of economic management were scarcely deemed to require original answers.”

Now that they did, Whitlam and his ministers resisted the idea that their policies and programs needed to be subordinated to the new economic realities. Labor had spent 23 years waiting to get into office and many of the government’s senior members had spent most of that time in opposition. Little wonder that they did not take kindly to the notion that they should now abandon their grand plans.

It was an attitude compounded by Labor’s distrust of treasury as a conservative redoubt and treasury’s own reluctance to tailor its advice to the priorities of a Labor government. The end result was chaotic economic management, characterised by wild swings in policy.

It was an area in which Whitlam failed the test of leadership, fluctuating between supporting treasury’s prescription of contraction, criticising it for imposing a credit squeeze by stealth, and supporting pump priming the economy by letting government spending rip. Having lost faith in Frank Crean as treasurer, Whitlam encouraged Cairns to take the job.

It was an ill fit, with Cairns too much of an iconoclast to follow treasury’s prescription of sacrifice and restraint. It was not until 1975, when Hayden took over treasury, that the budget started coming back under control. By then it was too late to save the government at the ballot box.

If it had not been the economy, other events would have destroyed the government. Of all the grand plans of ministers, the grandest were those of Rex Connor, the gruff, menacing figure who was 65 when he became minister for minerals and energy. His vision was of a massive program of national development to harness abundant resources and turn Australia into an energy superpower.

His folly was to be taken in by a dodgy commodities dealer called Tirath Khemlani, whose nickname was “Old Rice and Monkey Nuts” and who offered the lure of $US4 billion in loans from Middle East sources. The money never materialised and neither did Khemlani ever receive the fat commission he demanded but the political fall-out was enormous and sealed the fate of the government. Connor and Cairns both lost their ministerial jobs for misleading parliament over the loans affair. It provided opposition leader Malcolm Fraser with the “reprehensible circumstances” he used to justify blocking the 1975 budget.

The previous year, Whitlam had called the bluff of then opposition leader Billy Snedden, who had threatened to take the same action, by holding a double dissolution election, which Labor won with its majority reduced from nine to five.

This time Whitlam, his back against the electoral wall, was unwilling to succumb so easily. He refused to call an election, instead summoning all his formidable intellectual powers to turn the debate into the refusal of the conservatives to accept the legitimacy of a Labor goverment and against the Senate for holding the government to ransom. As the crisis dragged on, there was increasing nervousness in opposition ranks, with suggestions that some senators unhappy with Fraser’s tactics could break ranks and vote to pass the budget.

But Kerr intervened to sack Whitlam and install Fraser as caretaker prime minister on the proviso that he call an immediate election.

Briefly, at the start of the campaign, it seemed to some in the ALP that Whitlam might be able to turn the outrage over the dismissal into the main election issue. But the huge crowds that turned out to cheer Whitlam were an electoral mirage; The state of the economy and the government’s mismanagement were the real issues on which people cast their votes and they resulted in Fraser winning a record 55-seat lower house majority and control of the Senate.

The 1975 election also saw Whitlam make one of his periodic lapses of judgement. Desperate for funds for the campaign, Labor sought a $500,000 donation from Iraq’s Baath Socialist Party and Whitlam agreed to meet two Iraqi representatives over breakfast. Saddam Hussein was not yet president but the tyrannical and repressive reputation of Iraq’s ruling party was already firmly established. For the ALP to make itself beholden to any foreign government was bad enough, let alone such an unsavoury one.

When the story broke after the election, Whitlam was lucky to survive as leader. He had already offered the leadership first to Hayden, who refused, and then to Bob Hawke, who was not yet in the parliament. Whitlam soldiered on until the 1977 election, when Labor picked up only two seats, and after which Hayden agreed to take the helm.

Following the Hawke government’s election in 1983, Whitlam was appointed Australia’s ambassador to UNESCO, ironically the post to which the Fraser government had dispatched Kerr. On his return to Australia, he became chair of the National Gallery.

He never lost his zeal for public life, campaigning even in his nineties on issues he had been highlighting for 50 years or more, among them the importance of the UN and international conventions, reform of the Senate, fixed, four-year terms for state and federal parliaments, holding all elections on the one day, one vote one value, the republic and a new flag.

He also remained passionate about Labor as the party to build a better Australia, though often frustrated and sometimes openly critical of some of the actions of Labor governments. He was disappointed, too, in the failure and self-immolation of Labor leader Mark Latham, who had worked on his staff and whom he had nurtured.

Whitlam is survived by his sons Tony, Stephen and Nick and daughter Catherine. His wife Margaret died in 2012.

Gough Whitlam timeline