Amenhotep’s Book of the Dead: how a 3400-year-old mystery was solved

Tomb robbers, magic spells, scraps of papyrus: how a 3400-year-old mystery was solved in one eureka moment in Brisbane.

And the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time. - T.S. Eliot

“Are you sure you want to see it?” she asks, holding a blank grey rectangular box. There is a boy’s foot inside the box. An ancient Egyptian boy’s blackened foot, minus one toe, sawn roughly from his leg at the ankle by Egyptian tomb robbers, a macabre relic of a time when London’s upper classes held mummy parties, champagne wing-dings built around the unwrapping of a 3000-year-old face. Dr Brit Asmussen, senior curator of archaeology at the Queensland Museum, isn’t amazed or repulsed by the foot, she’s saddened by it. “Someone had done that to them,” she sighs. “They stole their remains.”

Are you sure you want to see it? A question of death and ethics, a test of worth. Are you sure he was meant for your eyes, this boy buried before the gods? “It’s an interesting moral question,” Asmussen says, “the moral ethical obligations we have to the deceased.”

Time is relative in this room, the museum’s sprawling backroom collection vault, dark corridors of towering sliding shelves holding ancient Torres Strait turtle shell instruments, jars of fossilised parasites, prehistoric stones, Cyprian, Roman, Greek antiquities, mummified Egyptian hawks and a giant Papua New Guinean slip drum the size of a nuclear warhead. Perspectives on time collapse in this room. Asmussen holds the boy’s foot, maybe 3000 years old. She remembers when she was eight years old, trawling through a remainders pile in a Gold Coast bookstore, striking upon a Time-Life book on Neanderthals, Emergence of Man. She asked her father, a hard-working shift worker, to buy it for her and he did. At home, her father caught the wonder on her face as she stared wide-eyed into the book’s black and white 1950s photographs and introduced his girl to the glories of National Geographic, to the intrepid paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, to ancient Africa. That was 30 years ago but universal scale, and this boy’s foot, make 30 years ago seem like last week. The boy’s foot makes April 2012 seem like yesterday.

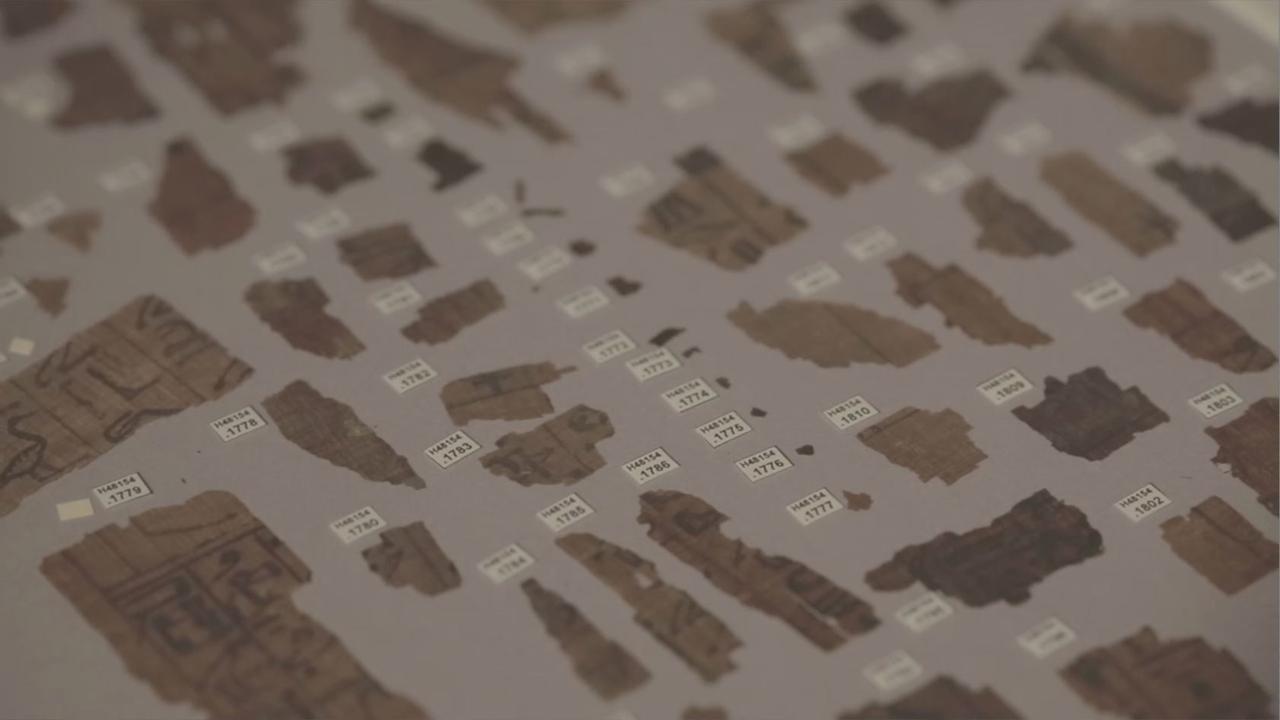

Asmussen slips on a pair of white cotton gloves. She walks on through the vault, takes a left turn into a corridor of shelving. She’s an archaeologist. It’s her job to trace moments in time, uncover and record the smallest details of objects, places, stories; pieces of the past’s backwardly expanding puzzle. She stops at a tall brown cupboard, pulls out a framed glass display case filled with fragments of ancient Egyptian papyrus, a hundred numbered and catalogued torn pieces, some the size of postage stamps, some like grains of pepper.

It’s an interesting moral question, the moral ethical obligations we have to the deceased.”

Of course she remembers the miraculous events of April 2012. She set those events in motion. She knows every small detail of that perfect and impossible moment in time when the 100-year international search for the last missing pieces of a prized and ancient Book of the Dead, belonging to an esteemed Egyptian builder named Amenhotep, ended in this very room. “One great big detective mystery,” she says, studying the papyrus beneath the glass, alive with Egyptian symbology, fragmented and strange images of animals and monsters and gods. Part of an instruction manual. “A collection of spells,” Asmussen says, “to help the deceased navigate the afterlife.” A book of magic.

Some archaeology romantics believe those final missing pieces wanted to be found. They say the series of events that led to their discovery was too preposterous to be anything but divine. The work of gods, they say, or Amenhotep himself, lingering in the afterlife, robbed long ago of the book that holds the key to his eternal paradise, left waiting, waiting, waiting for eight-year-old Brit Asmussen of the 20th century to find her book of archaeology in a Gold Coast remainders bin; waiting for her, many years later, to find four unidentified and unremarkable fragments of papyrus in a modest, unheralded museum in Brisbane, 14,350km from Egypt and 3400 years from the tears of his beloved wife Mutresti.

“I’m working on something at the moment which is kind of exciting,” says Dr Nicholas Reeves, Senior Egyptologist, University of Arizona, in a remarkably understated, decidedly English tone. “I think I’ve found extra chambers in the tomb of Tutankhamun. I think there is at least one more storage chamber and I think the tomb continues and there’s evidence to suggest that’s the tomb of Queen Nefertiti”. The lost queen, as she is known, died in the 14th century BC and her mummy was never found; if Reeves’ theory is correct it will be one of the most significant discoveries of the 21st century. Kind of exciting. Egypt’s minister of antiquities, Mamdouh Eldamaty, invited Reeves to Egypt to prove his theory using radar technology and announced that an inspection of the tomb seemed to confirm Reeves’ theory. “It’s another punt, but who knows?” Reeves says. “Nobody’s been in this position since Howard Carter.”

Dr Reeves took a punt almost four years ago when, working as Egyptian art curator at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, he discovered a gilded Egyptian face mask for the mummy of an unidentified man dating back to 1427-1400BC, in ancient Egypt’s 18th Dynasty. That mask bore a striking resemblance to a facial impression he had seen and recalled, by chance, on a fragmentary Egyptian coffin lid preserved in Eton College, Windsor, England, where he was previously a museum curator. “This mask had fragments of papyrus stuck to it,” Reeves says. “It had obviously had a sheet of papyrus glued on to it and then ripped off and the papyrus had been left where the glue had been attached. One of those pieces of papyrus had a name.”

Amenhotep. The same name inscribed on the Eton coffin lid, “Overseer of Builders of Amun, Amenhotep”, one of ancient Egypt’s greatest builders working in the prosperous reign of his namesake King Amenhotep II; a man who likely oversaw construction of the Great Temple of Amun in Karnak, near Luxor, one of the most popular tourist sites in modern Egypt.

This punt set Reeves on an exhaustive global archaeological investigation to reassemble the burial setting for Amenhotep in his once richly provisioned final resting place, likely in a tomb in Luxor, once the ancient Egyptian capital, Thebes. “Gradually, it was possible to build up an idea of what was in the tomb,” he says.

Picture how 1890s tomb robbers saw it, untouched and awe-inspiring, before they robbed it blind. A 3400-year-old mud-brick tomb with a ceiling decorated with black hieroglyphs on a red background. Amid his entombed belongings from daily life lay Amenhotep’s coffin made of expensive timber covered in shiny black resin varnish, decorated with a pendant heart amulet and, on the breast, a vulture with wings spread wide. A remarkably defined face on the coffin lid carved with such care it almost had to have been made in ancient Egypt’s hallowed royal workshops with the blessing of a king who held the deceased in high regard. Beside the coffin lay his wife, Mutresti, owner of a second fragmented mummy mask now in the Metropolitan Museum collection, also taken from the tomb.

There’s sadness in Mutresti’s mask’s facial impression, the melancholy of a mum left to raise their only child, a son, Sennefer, alone in the bustling world of ancient Egypt. “She certainly looks a bit sour to me,” says Reeves. “She doesn’t look like she’s having much fun.”

Pining for her late husband, perhaps, but not concerned for his journey through the afterlife, knowing he was buried with a detailed Book of the Dead to accompany him to eternity, safe in the knowledge that no human would ever be so inhuman as to interfere with his remains.

They imagined the afterlife as a kind of journey you had to make to get to paradise – but it was quite a hazardous journey so you’d need magical help along the way.”

Now see the tomb robber’s eyes light up, see him lick his lips as he roughly prises open Amenhotep’s dust-covered coffin lid. And there it is, Amenhotep’s Book of the Dead, a roll of papyrus 35cm wide and 20m long, neatly rolled up and resting on his mummified body, a section of the roll spread across and adhering to his head and breast. “The Book of the Dead isn’t a finite text,” says John Taylor, the British Museum’s ancient Egypt curator and the world authority on Book of the Dead texts. “It’s not like the Bible, it’s not a collection of doctrine or a statement of faith or anything like that – it’s a practical guide to the next world, with spells that would help you on your journey. They imagined the afterlife as a kind of journey you had to make to get to paradise – but it was quite a hazardous journey so you’d need magical help along the way.”

Amenhotep was venturing into the treacherous realms of gods. He would face a series of tests in his afterlife, challenges of character, knowledge and faith; asked questions by malevolent demons and untrustworthy deities. “Gods who are guarding gateways,” says Taylor. “If you don’t give the right answers to their questions at the gates, they can attack you because they have knives and snakes in their hands.” Without his book of spells to protect him, Amenhotep could be placed on a slaughter block, decapitated, turned upside down so his digestive process reversed, forcing him to eat faeces and drink urine for eternity. With it, he could draw from a corpus of almost 200 spells selected and tailored to suit the expected afterlife quest of a particular deceased. Spell 151: “O you who come seeking to repel my steps, you whose face is hidden; your hiding place is illuminated.” Spell 156: “You have your blood, O Isis; you have your power, O Isis; you have your magic, O Isis. The amulet is a protection for this Great One, which will drive away whoever would commit a crime against him.”

As he approached the gates of guardians Amenhotep could say, “I know you and I know your names”, then use information from his book to gain passage. He would walk the great Hall of Judgement, face 42 probing assessors, terrifying creatures with names such as “Blood-eater” and “Swallower of Shadows” before whom he would plead his innocence for sins such as killing, lying, damaging property, theft. Here, his heart would be weighed in the balance by the mighty Anubis, who would wait for Amenhotep’s heart to betray itself, containing as it did his whole lifetime of deeds, good and bad.

If he failed before Anubis he would be cast off to the Devourer of the Damned, a hybrid crocodile, lion and hippopotamus creature salivating by the scales. If he passed, his dead heart would be restored to him and he would proceed to kneel before Osiris, Lord of Eternity. And Mutresti would sleep well at night.

Now see the busy hands of the tomb robber, working fast to avoid detection from Egyptian authorities, as he rips Amenhotep’s guide through the afterlife from his breast. Reeves knows the day that happened. February 2, 1890. He pieced the date together from the diary entries of Emma B. Andrews, an associate of Theodore M. Davis, the New York lawyer who bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum his vast collection of Egyptian artefacts. Andrews writes of an “interesting old man” named Mohammed Mohassib, a middle man between tomb robbers and wealthy collectors, who presented to Davis a “mystic-looking black parcel, from which were taken the heads of two fine mummy cases” [Amenhotep’s and Mutresti’s masks] and “a basket of papyrus, which seemed to have been hastily stripped from the mummy case, as particles of it were still adhering to the case”. “It was very much broken,” Andrews writes. For the next century, fragments of Amenhotep’s Book of the Dead – “ripped apart by tomb robbers, cut into pieces by dealers”, Asmussen says – were bought, sold and traded across the world. Some 13 large sections landed at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

Around the time Davis purchased his sections, one Reverend Chauncey Murch, head of the American Mission in Luxor, purchased a 14.5m section later acquired by the British Museum, where John Taylor would study it so closely he would come to recognise its symbols and illustrations as surely as he would recognise a Shakespearean sonnet. Smaller scraps surfaced as decades passed – in Amsterdam, in a private collection in Stockholm – and the importance and legend of Amenhotep’s book grew. There are random fragments of other such guides to the afterlife in museums around the world but few as old as Amenhotep’s, few as significant.

His Book of the Dead was quite a long one. The more text you have, the more expensive it’s going to be, that makes it important.”

“It’s a very important book,” Taylor says. “His Book of the Dead was quite a long one. The more text you have, the more expensive it’s going to be, that makes it important.” Though one of the oldest book examples in the world, sections of its fabric, says Taylor, look “as though it was made a few weeks ago”. The roll features borders of five-pointed stars and sun-disks found on maybe four or five books in existence. Coloured illustrations, highest-quality calligraphy. “It was prepared by one of the top artists of the day,” he says.

In reassembling Amenhotep’s burial site, Reeves was temporarily lost down the rabbit hole of piecing together the global jigsaw puzzle of Amenhotep’s fragmented Book of the Dead. “You’re working on a jigsaw without the picture on the box,” says Taylor. Reeves tracked pieces across the world and emerged, like a dozen brilliant Egyptologists before him, with a notion that there was one significant section of the book missing: the lost pieces of Amenhotep’s puzzle, a key section of unknown length and content that would bring this magic book together. “I thought, ‘How extraordinary would it be to be able to put this thing together!’ ” says Reeves. “Then I receive this very excited email from John Taylor.” Taylor had just returned from Brisbane, Australia. Something strange had taken place, a most miraculous series of events.

Between April 16 and October 19, 2012, Queensland Museum hosted a travelling British Museum exhibition, Mummy: Secrets of the Tomb, and John Taylor flew to Australia to open it. To complement the exhibition, Brit Asmussen displayed some of Queensland Museum’s comparatively small holdings of Egyptian antiquities. She had started at the museum the year before and this was her first chance to familiarise herself with a wonderfully eclectic bag of bequeathed mummified hands, scarabs and rings, children’s toys, pottery vessels and an unidentified collection of papyrus fragments of unknown quantity wrapped in a series of mylar preservation packets. Asmussen set up her modest display near the museum gift shop, five quaint cases that guests could observe before venturing upstairs to the British Museum’s eye-popping showpiece exhibition. “So we were giving a curator-led tour of the Queensland Museum exhibition to John Taylor,” she says. “He was very interested in our collection. We had the mummified remains on display. He pointed out a gold ring on the mummified hand. He was interested in some gold on a mummified hawk. Then he sidled up to the second last case which had these four pieces of papyrus in it.”

Four little bits that we randomly picked, one of which contained Amenhotep’s name. That was the key.

Taylor froze. He put his face close to the display case. “You’ve got a name on this piece of papyrus,” he said. He began deciphering the hieroglyphs surrounding the animal imagery. “Amen… Amennnnnn…” His eyes moved to another set of hieroglyphs. “Oh, there’s a wife’s name here,” he said, excitedly. He read it aloud, piecing it together as he spoke: “Muuuuuutresti.”

“Then he stood back and he stood quiet,” Asmussen says. “And he took a breath. And I was thinking, ‘OK, he’s building the suspense here’. And then he said, ‘Do you have any more of these fragments?’ And I said, ‘Yes, we have quite a lot upstairs in the collection area, would you like to see them?’” Taylor responded in a quick, sure whisper. “Yes, I think I would,” he said.

Asmussen ushered Taylor upstairs to the museum vault where a small team began retrieving the series of mylar packets from storage. “We weren’t sure how many pieces we actually had because they were all in mylar packets,” Asmussen says. “We thought we might have a few hundred pieces. But, no.”

They had 8000 pieces.

Taylor postponed his commitments to the touring exhibition to hole himself up in the museum’s conservation lab, working solidly and silently for several straight hours, head down assessing an endless stream of highly fragmented papyrus pieces Asmussen’s team produced from the vault. Finally, Taylor spoke. He was in no doubt. He had just stumbled on the last missing pieces of Amenhotep’s Book of the Dead. “We were like, ‘Oh. My. God’,” Asmussen says.

“When you go to a museum in any part of the world and you see bits of Egyptian papyrus, what you normally expect is that they will be a mixture of different pieces from different documents and different periods and you can’t really do much with them,” Taylor says. “In this case, as soon as I saw all the others I realised this is all one document because it was totally consistent in the style of writing and the vocabulary that was being used at the time. I thought, ‘Well, potentially this could all be put together now’.”

Asmussen laughs, shakes her head. “It’s mind-boggling,” she says. She knows exactly why she chose those four particular pieces from the innumerable papyrus fragments in her collection. “We’ll pick a big bit with an animal on it,” she recalls thinking. Images of animals on the papyrus would match the theme she was leaning to in her display cases – the role of animals in ancient Egyptian daily life. Asmussen’s not versed in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. Her museum staff had long known the papyrus pieces were from a Book of the Dead; they had no possible way of knowing whose. There was, Asmussen ponders, maybe only one man in a world of seven billion people who might have passed that display case and recognised the true significance of those four pieces, a man possessing what he calls “a mental memory bank” of papyrus symbology. For Taylor to even pause over the random papyrus pieces in the display case, fate had to ensure Asmussen pulled four pieces out of a collection of 8000 that happened to have enough lettering for him to recognise an owner’s name and not move on to the pressing business of launching an exhibition, leaving the papyrus pieces to return, uncelebrated, to the vault for another 100 years.

“Four little bits that we randomly picked, one of which contained Amenhotep’s name,” Asmussen gasps. “That was the key. If that hadn’t have happened, it would be just any other bit of papyrus that he would have seen and passed over. He wouldn’t have been able to connect the dots back to Amenhotep.” The moment makes her giggle. “How random is that?”

It might be more than random, laughs Reeves. “It is very strange. It’s almost as if… things attract. It’s an odd feeling. Sometimes things do come together. Sometimes that magic does work.”

“Uncanny,” agrees Taylor. “Particularly the fact so much of the book was back in London in my place of work. In one out of 100 cases does a hunch turn out right. It actually really was what I was hoping it was. That was the sensation. It is one of the main moments of discovery in my career, because it is just such a neat solution to the problem. Where is the rest of this papyrus? And there it is, right in front of you.”

It’s an odd feeling. Sometimes things do come together. Sometimes that magic does work.”

Those 8000 fragments travelled a long way to land in front of Taylor.While Asmussen’s team began the laborious task of digitising, numbering and framing the missing fragments, she began an archaeological side journey down their curious path from Amenhotep’s ancient tomb to her Brisbane workplace. “We wanted to understand our place in this big international mystery,” she says. “This great archaeological story. It became a personal thing for me.”

She trawled old copies of the Brisbane Courier newspaper, found a 1932 reference touting “the oldest book in Queensland”, a reference to several papyrus pieces stored in the Queensland Museum. A shrewd museum librarian, Meg Lloyd, dug up mysterious archived correspondence from 1902 between then-museum director Charles De Vis to a Professor E.M. Crookshank: The case arrived safely last week …they will form very attractive and instructive items in our little museum… I have now a couple of specimens of the rare marsupial mole from Central Australia. I would spare you one with much pleasure whenever you feel disposed for another exchange.

Edgar March Crookshank, Asmussen found, was a professor of comparative anatomy and bacteriology at Kings College, Cambridge, and an avid collector of Egyptian antiquities. She discovered another Courier reference to a May 26, 1902 lecture given by the visiting Professor Crookshank to the Royal Society of Queensland, 12 years after the robbery of Amenhotep’s tomb. “He’s in Queensland doing a lecture tour and we think at one of these lectures he must have met Charles De Vis,” Asmussen says. “He must have mentioned he had this collection of Egyptian artefacts. His interest was in animals and bacteriology and he was interested in obtaining some specimens and maybe they could do a swap for his Egyptian objects.”

From the museum archives emerged a document listing Crookshank’s requested specimens in exchange for Amenhotep’s priceless Book of the Dead fragments, from a feathertail glider to a crimson rosella to a Queensland lungfish. He traded 8000 fragments of ancient Egyptian wonder for a menagerie of native fauna.

The discovery of Amenhotep’s missing pieces has sparked partnerships between Queensland Museum and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts and Queensland University of Technology using mathematicians and supercomputers to digitally detect and match pieces of Amenhotep’s virtual jigsaw puzzle across the world. “The world is linked in very strange ways,” says Reeves. “It’s all coming together. The discovery of these pieces means this fabulous papyrus will be reassembled. We’ve got enough information in our fragments to restore this book, at least digitally. It’s one of the finest papyri known from the period. It is really worth the effort to put all these pieces together. And John Taylor has those skills.”

I hope we are doing him a favour, doing him some sort of justice, thousands of years later.”

“What we’re trying to do all these years on is preserve the information for people of the future,” says Taylor. “But also to try to put back together what was originally provided for this man. I hope we are doing him a favour, doing him some sort of justice, thousands of years later.”

When he gazes upon the fragments of Amenhotep’s puzzle, Taylor is reminded of what Mutresti might have hoped for her late husband. She would have hoped his name would be spoken through time. She would have hoped he made it through the Hall of Judgement, past the Devourer of the Damned and on to his eternal paradise, to board the sun-god’s boat and sail to the Field of Reeds, a familiar world to him, a dry land split by waterways where he would watch rich crops grow to great heights, a place not unlike the Nile River lands he left behind. “I think that’s one of the most appealing things about it,” Taylor says. “What they really wanted was to go back home at the end of the journey.”

When Nicholas Reeves ended his journey through the tomb of Amenhotep he was moved to quote T.S. Eliot above his subsequent museum research paper.

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Mutresti wanted her husband to come home. Paradise was a kitchen and a meal together with their son. “If you can relate to a person on that level then time is irrelevant,” says Asmussen. She thinks for a moment of her own lost loved ones. “I’ve lost a couple of significant people quite close to me,” she says, ambling along the vault corridors. “I think maybe that’s informed my archaeological perspective about the person in the past and trying to understand what their life is like because they’re not there. But, you know, they pop up for us,” she says.

They’re in our dreams, the departed. They’re in the things we remember, they’re in the archaeology of a grandchild’s smile, in the way someone laughs, the things we touch, taste and smell, the songs we hear on the radio, the stories we tell around the dinner table. Time collapses in those moments and, like magic, they’re with us again. They’re home.

Pictures: Eddie Safarik