Sofronoff report reveals Shane Drumgold lied during Bruce Lehrmann rape case

Of all his misconduct, Shane Drumgold’s repeated attempts to keep evidence of doubt about Brittany Higgins’ claims out of the hands of defence lawyers was the most serious, report finds.

ACT chief prosecutor Shane Drumgold knowingly lied to the Supreme Court, engaged in serious malpractice and grossly unethical conduct, “preyed on a junior lawyer’s inexperience”, betrayed that junior lawyer who trusted him, and treated criminal litigation as “a poker game in which a prosecutor can hide the cards,” the Sofronoff Inquiry has found.

In findings that are certain to end Mr Drumgold’s career as ACT Director of Public Prosecutions and may lead to criminal prosecution against him for perverting the course of justice, inquiry head Walter Sofronoff KC ruled that every one of the allegations made by Mr Drumgold that sparked the inquiry was baseless.

In the report, obtained by The Australian, Mr Sofronoff found that Mr Drumgold had lost objectivity during the prosecution of Bruce Lehrmann for the alleged rape of Brittany Higgins and “did not act with fairness and detachment as was required by his role”.

The ACT government received Mr Sofronoff’s report on Monday but has refused to release the findings until the end of the month, as senior officials pore over the 600-page document.

Mr Sofronoff said he was “deeply disturbed” by Mr Drumgold’s ignorance of ethical principles and accused him of a “Pilate-like detachment”, invoking the moment Pontius Pilate washed his hands of Jesus’s fate, letting the mob decide who should be crucified.

Among the astonishing catalogue of misconduct and dishonesty found by the inquiry against Mr Drumgold are:

- That he made representations to the Chief Justice Lucy McCallum in the proceedings against Mr Lehrmann that were “untrue” and “an invention of his own”;

- That he was guilty of a “serious breach of duty” by failing to comply with the “golden rule” of disclosure that sits at the heart of a fair trial by failing to disclose documents where there was “simply no doubt” that those police investigation documents should have been disclosed;

- That the DPP failed to adopt the rule of thumb used by wise and experienced prosecutors – “if in doubt, disclose”;

- That the DPP “kept the defence in the dark about the steps he was taking to deny them the documents that meant they were in no position to mount a challenge”;

And that he “constructed a false narrative to support a claim of legal professional privilege”.

“The result has been a public inquiry, which was not justified by any of his allegations, that has caused lasting pain to many people and which has demonstrated his allegations to be not just incorrect, but wholly false and without any rational basis,” Mr Sofronoff concluded.

“The cost of a six-month public inquiry – in time and money, in lost work, and personal and professional consequences – has been huge,” he said.

Even if Mr Drumgold had succeeded in dishonestly preventing Mr Lehrmann from obtaining material that could have helped his defence, any conviction would have been set aside on the ground of a miscarriage of justice, Mr Sofronoff concluded.

In one of many particularly pointed findings, he said he preferred the evidence of TV presenter Lisa Wilkinson and prosecutor Skye Jerome over Mr Drumgold.

“I do not believe any part of Mr Drumgold’s purported recollection unless it is consistent with the recollection of those witnesses,” he said.

Mr Sofronoff said he had considered whether he should invite Mr Drumgold to make a submission as to whether he was a fit and proper person to remain on the roll of barristers and to hold office as the Director of Public Prosecutions.

He said he accepted the submission of Mr Drumgold’s counsel, Mark Tedeschi SC, that it was not within his terms of reference, and that, in any case, “it would not be right for me to do so”.

However, several senior lawyers have told The Australian that if Mr Drumgold was found to have deliberately misled the court to prevent defence lawyers obtaining police documents, he may face an investigation for attempting to pervert the course of justice.

The Office of the DPP will now also face a multimillion-dollar claim by Mr Lehrmann on the grounds of malfeasance, following Mr Sofronoff’s findings of gross misconduct by Mr Drumgold.

By contrast, Mr Sofronoff found that police investigators and their immediate superior officers “performed their duties in absolute good faith, with great determination although faced with obstacles, and put together a sound case”. They conducted “a thorough investigation,” Mr Sofronoff found.

Although police had made mistakes, some of which had caused Ms Higgins unnecessary pain, “none of these mistakes actually affected the substance of the investigation and none of them prejudiced the case,” he said.

Likewise, Mr Sofronoff found that Victims of Crime Commissioner Heidi Yates, who often appeared at Ms Higgins’ side during the trial, had been subjected to “a degree of unjustified public criticism” because of a general lack of understanding about what the law required her to do.

Ms Yates’ presence at Ms Higgins’ prejudicial speech after the jury was discharged was also due to no fault of her own, he said.

“Her sole purpose at that time, consistently with her statutory duty as well as with human decency, was to ensure, so far as she could, the wellbeing of her client.”

The only substantial finding by the inquiry in Mr Drumgold’s favour was that he was justified in bringing the prosecution against Mr Lehrmann. However, no one, including the police, had submitted he was wrong to do so.

Drumgold’s failure to disclose Moller Report

Perhaps the most serious finding by Mr Sofronoff concerns Mr Drumgold’s repeated attempts to keep the so-called Moller Report out of the hands of Mr Lehrmann’s defence team, even though they were legally entitled to have it.

The Moller Report, first revealed by The Australian, consisted of an internal police executive briefing note by Detective Superintendent Scott Moller that detailed discrepancies in Ms Higgins’ evidence and suggested police didn’t think there was enough evidence to prosecute Mr Lehrmann.

Mr Drumgold tried to stop the defence obtaining this and other documents that became known as the Investigative Review Documents.

First, the DPP claimed these documents were not disclosable to Mr Lehrmann’s defence team.

In his report, Mr Sofronoff said that “wise and experienced prosecutors always adopt the rule of thumb, ‘if in doubt, disclose’ ”.

In fact here, there was “simply no doubt” that the investigative review documents should have been disclosed to the defence.

Mr Drumgold had breached the prosecutors “golden rule” of disclosure.

On the second day of the public hearings, Mr Drumgold told the inquiry that he thought disclosure of internal police investigations that suggested inconsistencies in her evidence would be “crushing” to Ms Higgins.

That, said Mr Sofronoff, “is not a proper basis for a prosecutor to resist disclosure of documents”.

Mr Drumgold’s next claim, that the documents were subject to legal professional privilege – made without him having read them all, and without checking with police – was also “wrong and untenable”.

Mr Drumgold knew that legal privilege over these documents was for the police, not him, to claim. He never picked up the phone to ask police.

Mr Sofronoff found that Mr Drumgold knew the AFP had not made a claim of legal professional privilege over these documents and that the AFP made no mention of intending to make such a claim.

When Mr Lehrmann’s legal team made an application to the court for disclosure, Mr Drumgold instructed solicitors in his office to draft an affidavit to support non-disclosure on the basis that the documents were protected by legal professional privilege.

Mr Drumgold emailed two solicitors in his office about drafting the affidavit.

He had sidelined the more senior member of his staff who had queried the source of the information and instead “procured a youngster to do the job”.

“Mr Drumgold could not name a source (for the privilege claim) in his instructions to his staff member because, as Mr Drumgold admitted in his evidence, he himself was the source.” Instead, he “required his fledging staff member, newly admitted”, to unknowingly swear an affidavit that did not comply with the rules about the source of information being sworn. Mr Drumgold sent this most junior lawyer wording for the affidavit that claimed the police documents sought by the defence were privileged.

“Mr Drumgold knew, or ought to have known, that when relying upon hearsay evidence in the circumstances, the deponent is required to identify the source of the information and the grounds for the belief.

“If he did not know, that is a very serious instance of gross incompetence. If he did know, he was intending to mislead the court by deliberate deception. I am of the opinion that Mr Drumgold knew the rule.”

Mr Sofronoff found that by submissions and by the false affidavit, Mr Drumgold “deliberately advanced a false claim of legal professional privilege and misled the court.

Mr Drumgold made statements of fact to the Chief Justice that the AFP were making a claim of privilege over documents when he knew they had not.

The DPP’s claim that the documents were covered by legal professional privilege “had no factual basis … and no such opinion could honestly be formed by a competent lawyer”, Mr Sofronoff said.

The inquiry found that Mr Drumgold had tried to use “dishonest means to prevent a person he was prosecuting from lawfully obtaining material”.

“Had the defence, by their professionalism and persistence, not obtained (the internal police investigative documents) despite the improper obstruction they faced, and had the documents come to light after a conviction, in my opinion the conviction would have been set aside on the ground of a miscarriage of justice.

“This would have meant wasted expense for the government and for Mr Lehrmann and it would have meant additional anxiety for those involved,” Mr Sofronoff said.

“Mr Drumgold kept the defence in the dark about steps he was taking to deny them the documents,” Mr Sofronoff said. That meant defence lawyers were in no position to mount a challenge.

“Criminal litigation is not a poker game in which a prosecutor can hide the cards,” he observed.

Mr Sofronoff described Mr Drumgold’s submission to the inquiry that it was not appropriate for him to give legal advice to the AFP over disclosing the Moller Report as “Pilate-like detachment”, which was at odds with his “later vigorous assertion of a claim of privilege”.

Mr Drumgold’s representation that it was an error that the documents had been listed as disclosable in a document known as the Disclosure Certificate served on the defence was untrue and was “an invention of his own”.

Mr Sofronoff found that Mr Drumgold’s claim about the disclosure certificate was “another invention”. “Mr Drumgold constructed a false narrative to support a claim of legal professional privilege” that was “utterly untenable”. Nor was Mr Drumgold “confused”, as Mr Tedeschi had suggested to the inquiry.

Mr Drumgold knew exactly what he was doing, when having been “foiled” by a more senior DPP lawyer, he asked a junior staffer “to do something improper”.

“Quite apart from Mr Drumgold’s misconduct in misleading the Supreme Court in a criminal case … he egregiously abused his authority and betrayed the trust of his young staff member to whom he owed a duty to be a mentor and role model.

“Mr Drumgold preyed on the junior lawyer’s inexperience,” Mr Sofronoff said.

“Had the defence, by their professionalism and persistence, not obtained (the police documents) despite the improper obstruction they faced, and had the documents come to light after a conviction, in my opinion, the conviction would have been set aside on the ground of a miscarriage of justice.”

The Logies speech and the note

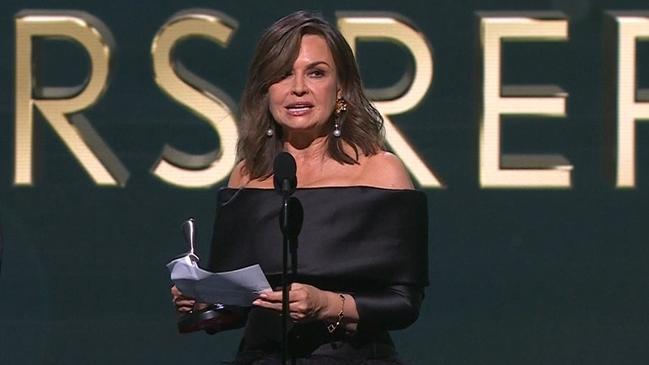

Mr Sofronoff made serious adverse findings against Mr Drumgold over his use of a supposedly contemporaneous note made of a discussion he held with Lisa Wilkinson four days before her Logies speech.

Mr Drumgold said he warned her about the danger of prejudicing Mr Lehrmann’s upcoming rape trial. Wilkinson rejected that, saying Mr Drumgold “did not at any time” give her the warning he claimed.

Mr Drumgold presented a note of the conference to Chief Justice McCallum as if it had been written contemporaneously by a junior lawyer present at the meeting. It hadn’t.

That part of the note that was critical to the Chief Justice was effectively written by Mr Drumgold days later after Wilkinson gave her speech – and after it became clear the upcoming trial was in jeopardy because of it.

Mr Sofronoff found that Mr Drumgold “knowingly lied to the Chief Justice”.

“For the Chief Justice’s purposes, the note was not contemporaneous. (The junior DPP staffer) had not made the note. Mr Drumgold’s statements to the Chief Justice were false. The note was nothing more than a copy of an email which Mr Drumgold had written five days after the meeting and which purported only to record his ‘best recollection’.”

Mr Sofronoff dismissed a claim by Mr Drumgold’s counsel that those untruthful statements were just a mistake.

“I reject that a prudent and experienced barrister would behave in that way or make a mistake of this calibre,” Mr Sofronoff said. “This is a wholly untenable excuse for a barrister of the seniority and experience of Mr Drumgold.

“He could not have forgotten that the material words in the note were words that he had written himself (choosing to do so in the third person) on the day before.”

Mr Drumgold had “ample opportunity to correct his untruths at many points” but did not do so.

“He must have known that (Chief Justice) McCallum had found, as a matter of fact, that Ms Wilkinson had engaged in wilful defiance of his ‘appropriate’ warning and that her finding was based entirely on the proofing note.

“I do not accept that Mr Drumgold’s misstatements about the nature of the note were a mere mistake that he made.”

Mr Sofronoff said it was true that Wilkinson was a very experienced broadcaster who should have appreciated the likely effect of her intended words, but Mr Drumgold’s duty of care was not to her but to the court, “to do what is required to preserve the integrity of the administration of criminal justice”.

“Instead, he did nothing and thereby left alive a threat to the trial. A postponement might have endangered Ms Higgins’ health, which Mr Drumgold knew was fragile. It imperilled Mr Lehrmann’s right to the presumption of innocence. It left Ms Wilkinson under the false impression that she was at liberty to give the speech.”

Mr Sofronoff agreed with Mr Lehrmann’s barrister Steven Whybrow’s submission that after the Logies speech, an application for a temporary stay of the imminent trial “should be brought by the Director, not opposed by the Director”.

It was, however, no surprise that the DPP opposed the stay. After all, Mr Sofronoff found that while Wilkinson had been wrongly accused in court of causing the stay, in fact “a successful application for a stay had resulted from (Mr Drumgold’s) failure to warn” Wilkinson.

Baseless claims of political interference

At the trial, Mr Drumgold told the jury that “political forces” explained the delay in Ms Higgins’ complaint to the police, and that “it is abundantly clear from the evidence and actions of Senator (Linda) Reynolds during this trial that those political forces were still a factor.

Mr Drumgold alleged strong political forces on numerous occasions during the trial. Mr Sofronoff found that “there was not a single piece of evidence that anyone had applied pressure upon Ms Higgins that could legitimately be described as ‘strong political forces’ ”.

During the trial, Senator Reynolds strongly denied discouraging the young staffer from making a complaint for political or other reasons. “Notwithstanding this evidence, Mr Drumgold submitted to the jury that the ‘evidence and actions of Senator Reynolds during this trial’ indicated that ‘political forces’ were still extant,” Mr Sofronoff said.

In his cross-examination of Senator Reynolds, Mr Drumgold claimed she “arranged” for her partner to attend court and that he had been discussing Ms Higgins’ evidence with her. But there was no evidence of this and it was “tantamount to an allegation of an attempt to pervert the course of justice”, Mr Sofronoff said.

It is a fundamental principle of ethical legal practice that suggestions to a witness should not be made unless they are supported by reliable information. Otherwise, the barrister could abuse the privilege of immunity from defamation afforded to counsel in order to seek an unfair advantage.

“Mr Drumgold was examined about his understanding of this ethical principle. His ignorance deeply disturbed me … He fails to understand the difference between putting forward to a witness an allegation of misconduct as a fact and asking a witness whether or not something is a fact.”

Mr Drumgold had also attempted to discredit Senator Reynolds by questioning her about a text she had sent to Mr Whybrow requesting a copy of the trial transcript to be sent to her lawyer.

“Mr Drumgold had no basis upon which to put that suggestion which was intended to impute impropriety in Senator Reynolds in the eyes of the jurors,” Mr Sofronoff said. Ms Higgins had issued legal proceedings against Senator Reynolds and she had been advised by her lawyer to get the trial transcript in order to provide her with advice.

“A phone call to the lawyer would have revealed the truth about that matter to Mr Drumgold,” Mr Sofronoff said.

The same could be said about the presence in court of Senator Reynolds’ partner, Mr Sofronoff observed. Relatives and friends of witnesses frequently attended cases to observe proceedings. In this case, some friends and supporters of Ms Higgins attended.

“The suggestion that Senator Reynolds as well as her partner were engaging in potentially criminal conduct was an improper one and should not have been made,” Mr Sofronoff said.

“Likewise, it was improper to put to Senator Reynolds that she was ‘politically invested’ in the outcome of the trial. There was not only no basis for this but the nature of the political investment, why it might be important politically for there to be an acquittal, was never identified.”

Mr Sofronoff said that he accepted Mr Drumgold’s submission that “he acted out of ignorance but I must say that I am taken aback that a senior counsel holding the office of DPP should be so ignorant of this fundamental principle”.

“The suggestions made by Mr Drumgold had no basis at all and should not have been made.

“They were intended to, and might have, affected the outcome of the trial adversely to Mr Lehrmann and the conduct was, therefore, grossly unethical.”

Fiona Brown treatment

Another disclosure issue during the trial concerned an email sent to the Office of the DPP during the trial by Fiona Brown. Ms Brown was described by Mr Whybrow as the most important witness, after Ms Higgins, because she spoke to Ms Higgins soon after the now infamous security breach at Parliament House.

Ms Brown emailed the ODPP to express her view that Ms Higgins, upon her return to the witness box after a break of some days, gave demonstrably false evidence. Ms Brown was concerned that the jury had been left with the wrong impression that Ms Higgins had said Ms Brown had offered to pay her out to go to the Gold Coast during the election.

Ms Brown had done no such thing. She did not have the power to offer such a payment; indeed, it would have been improper for her to do so.

Mr Sofronoff found that the full context of what Ms Higgins had said in the witness box about being offered to work from the Gold Coast diminished the probative significance of Ms Brown’s email.

Mr Sofronoff found that Mr Drumgold’s submission that he did not need to disclose Ms Brown’s email to defence “followed a sound application of the threshold of disclosure, but it produced the result that the defence were deprived the opportunity to explore a legitimate forensic inquiry.”

“Such an outcome is inconsistent with the purpose of disclosure to facilitate a fair trial and assist the court to arrive at the truth.”

Brittany Higgins’ counselling notes

Mr Sofronoff found that the police had erred in handing Ms Higgins’ confidential counselling notes to the defence and to the prosecution but accepted it had not been done intentionally.

Evidence at the inquiry revealed that the only person who read the protected counselling notes was Mr Drumgold. Mr Sofronoff was highly critical of Mr Drumgold, who said he had read the counselling notes to determine “how much harm” the disclosure to the defence could cause to Ms Higgins. He was not permitted to do so, Mr Sofronoff found, because there is “no kind of exception made in favour of the prosecutor” in the Evidence Act.

“Having read the notes, Mr Drumgold was in a position where he held information about the matter that the defence did not … This was unfair because it gave him a forensic advantage.

“This demonstrated a disturbing lack of awareness in Mr Drumgold’s understanding of his prosecutorial duties…”

Mr Sofronoff said that having wrongly put himself at an advantage, Mr Drumgold had three choices open to him: he could have withdrawn from the case; he could have brought an application to enable him to disclose their content to the defence; or he could have supported any such application brought by the defence.

“By doing none of these things, Mr Drumgold breached his duty as prosecutor,” Mr Sofronoff said.

“It is hard to see how there could be a fair trial in these circumstances,” he concluded.

DPP’s relationship with police

On November 1, 2022, Mr Drumgold wrote an angry letter to ACT Chief Police Officer Neil Gaughan making a series of what Mr Sofronoff called “scandalous allegations” about political interference in the investigation and trial of Mr Lehrmann.

“The adverse suspicions that Mr Drumgold formed during his early interactions with the investigators predisposed him to see non-existent malignancy in benign interactions between the police and the defence at the trial,” Mr Sofronoff found. Mr Drumgold and members of his team had complained police were speaking with the defence at the trial during adjournments. However, Mr Sofronoff found Mr Drumgold’s claim the interactions amounted to interference in the case was “baseless”. It was not surprising, said Mr Sofronoff, that the police felt deep antipathy towards the DPP, since the feeling was mutual.

“Mr Drumgold did not seem to appreciate that mutual trust is a two-way street. It was he who, at the first opportunity, formed the baseless opinion that the investigators were improperly trying to thwart a prosecution.”

Mr Sofronoff found that Mr Drumgold “advanced nothing resembling evidence to support the serious allegations of impropriety that he levelled against the police, defence and Senator Reynolds”.

Instead, “as was submitted on his behalf, he was relying upon ‘perceptions, suspicions, or concerns’ ”. Mr Drumgold claimed he had no choice but to write his letter to the Chief Police Officer, but Mr Sofronoff pointed out that he could have reported his concerns to the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity (now part of the National Anti-Corruption Commission), which ended up investigating the case anyway.

“As we now know, that agency’s valuable time has been wasted by the need to investigate very serious allegations made by a high officer of government that he has finally admitted were baseless.”

Mr Sofronoff said that allegations of wrongdoing in the public sector “require discretion and confidentiality while the matters are investigated. Allegations of corruption are extremely serious and, without a proper basis, are defamatory. They can damage public confidence in institutions if not handled properly.

“This inquiry has thoroughly examined the allegations in Mr Drumgold’s letter. Each allegation has been exposed to be baseless. Late in giving his oral evidence, Mr Drumgold finally resiled from his scandalous allegations.”

Mr Sofronoff said that “any official writing a letter of that kind would also know that copies of the letter would have to pass through many hands and that there was a real risk that it would be made public. In fact, it was with the help of Mr Drumgold himself that the letter defaming others made its way into a newspaper.

“The allegation of political interference was particularly wicked because it was an allegation that had a tendency to lessen the community’s confidence in the system of administration of justice and was made without the slightest evidence to support it.”

Drumgold’s speech at the courthouse

On November 9, 2022, Ms Higgins’ lawyer contacted Mr Drumgold to say the young woman did not want to proceed with a retrial because of mental health concerns. Two weeks later, the lawyer sent Mr Drumgold two psychiatrists’ reports and requested on behalf of Ms Higgins that Mr Drumgold discontinue the prosecution.

On the morning of December 1, 2022, legal representatives for the parties attended the Chief Justice’s chambers and Mr Drumgold informed them he would be discontinuing the prosecution “because the ongoing trauma associated with the prosecution presented a significant and unacceptable risk” to Ms Higgins’ life.

Mr Sofronoff found Mr Drumgold had made the correct decision. “In the circumstances, Mr Drumgold’s decision to discontinue the prosecution was right. He could not have reasonably continued knowing the grave risk to Ms Higgins’ health,” he said.

However, when Mr Drumgold made a speech outside court announcing his decision, he stated that he still believed there was a reasonable prospect of convicting Mr Lehrmann and applauded Ms Higgins for her “bravery, grace and dignity”.

“Mr Drumgold’s comments were improper. They undermined the public’s confidence in the administration of justice and (it) was a failure in his duty as DPP,” Mr Sofronoff said.

He said there was a well-established principle that a prosecutor should not make any public comment about a trial which they have prosecuted.

Mr Drumgold’s comments implied that he “personally believed Ms Higgins’ complaint of rape was true and that, as a consequence, Mr Lehrmann was guilty”.

“The comments were improper and should not have been made.

“It was not necessary for Mr Drumgold to express his views on the prospects of conviction at the time of discontinuance.

“Nor was it his function to identify himself with the complainant to a degree that he made a public statement of support.

“The motive for this was good; the decision was bad.”

Mr Drumgold owed Mr Lehrmann the presumption of innocence and was not entitled to “use his high office to impute guilt in a public forum”.

FOI release of letter

On the morning of Saturday December 3, 2022, The Australian published an article with the headline, Police doubted Brittany Higgins but case was ‘political’, that revealed senior police officers believed there was insufficient evidence to prosecute Mr Lehrmann but could not stop Mr Drumgold from proceeding because “there is too much political interference”, according to diary notes made by Superintendent Moller.

The article also revealed that in a separate executive briefing, Superintendent Moller advised that investigators “have serious concerns in relation to the strength and reliability of (Ms Higgins’) evidence, but also more importantly her mental health and how any future prosecution may affect her wellbeing”.

The day before the article appeared, Mr Drumgold had withdrawn the charges against Mr Lehrmann, citing concerns for Ms Higgins’ mental health, so his retrial would no longer proceed.

In his report, Mr Sofronoff said he had required Mr Whybrow, police and DPP staff to disclose their communications with the media about the case, but “there is no evidence tendered before me that explains how and when the briefing documents and the diary note were disclosed to The Australian”. That Saturday morning, Guardian journalist Christopher Knaus called Mr Drumgold and alerted him to the article, which Mr Drumgold read while on the phone to the reporter.

Mr Drumgold said he felt “‘highly emotional at the personal attack and the unfounded accusations of misconduct” that the article was directing at him”.

He “felt a sense of absolute devastation”. He had never been the subject of such a “malicious, serious and unfounded personal public attack” before, he said.

Mr Drumgold gave the journalist a written response: “I am greatly concerned that potentially legally protected material may have again been unlawfully distributed. Given myself and others have already raised concerns about matters that are currently under investigation, it would not be appropriate to comment further whilst investigations are under way.”

In fact, there were no “investigations under way”.

On the Monday following, Mr Knaus submitted a Freedom of Information application for “a copy of any documented complaint made by the DPP about the conduct of police during the matter of R v Lehrmann, which was sent to ACTP in the months of October or November 2022”.

Mr Drumgold authorised the release of the unredacted letter containing the DPP’s suspicions of impropriety against named police officers and Senator Reynolds, without any of the consultations or redactions required by law.

The letter contained legal advice over which the AFP could have claimed privilege, the viability of which could have been affected by public disclosure of the letter, Mr Sofronoff said.

“So much would have been blindingly obvious to any rational person with Mr Drumgold’s knowledge of the matter,” Mr Sofronoff said.

The FOI application was determined and executed within four hours of being considered for the first time.

When the Chief Police Officer discovered the letter had been released and rang to complain, Mr Drumgold told him that “he did not know about the FOI or the fact that it had been released”.

“Mr Drumgold’s statements to him were false”, Mr Sofronoff concluded.

Mr Drumgold’s office later sent out a redacted version of the letter.

The Guardian had already published an article quoting Mr Drumgold’s allegations “but acting with scrupulous adherence to the ethics of journalism, Mr Knaus did not name the individuals concerned”, Mr Sofronoff said.

Chief Police Officer Neil Gaughan made a complaint to the Ombudsman about the release of the letter. Mr Drumgold explained his failure at the inquiry by asserting that it was up to an executive officer of the ODPP, Katie Cantwell, to decide on requirements being met under the FOI Act.

Mr Sofronoff said: “I reject Mr Drumgold’s explanation as false.”

Mr Drumgold had given Ms Cantwell “an unambiguous verbal instruction to her to release the unredacted letter” to The Guardian.

Mr Sofronoff concluded that “the evidence before me has revealed that the explanations proffered by Mr Drumgold to the Ombudsman, ACTP and to me were untrue. It is also clear to me that he has shamefully tried falsely to attribute blame to Ms Cantwell who, in every respect, performed her duty assiduously and in accordance with instructions that she was bound to follow from the Director.”

Conduct of police

The police who conducted the investigation into Brittany Higgins’ rape claims were largely exonerated by Mr Sofronoff, who found that no officers had breached a duty or acted improperly.

“The evidence before me showed that the investigators consistently acted in good faith and conducted a thorough investigation … Nobody suggested to me that the investigation was flawed in any way.

“On the contrary, the course of evidence demonstrated to me that the investigators and their immediate superior officers performed their duties in absolute good faith, with great determination although faced with obstacles and put together a sound case.”

The police had made mistakes, Mr Sofronoff said, including conducting a second interview with Ms Higgins that was not likely to produce anything useful and which caused her distress.

“None of these mistakes actually affected the substance of the investigation and none of them prejudiced the case.”

There was also a lack of understanding by police about the discretion to lay a charge which Mr Sofronoff found concerning. “That was not the fault of individual officers but of the AFP in its failure to have a clear policy”, he said.

Mr Sofronoff also examined statements by police first revealed in The Australian that there was insufficient evidence to prosecute Mr Lehrmann but that they could not stop Mr Drumgold from proceeding because “there is too much political interference”.

Mr Sofronoff found that police were not alleging a deliberate attempt by any person to interfere but referring to “the environment that we were in at the time” and the collective pressure that they were feeling.

It was this reference, discovered by Mr Drumgold, which fuelled the DPP’s suspicions that police were deliberately undermining the prosecution, a belief Mr Drumgold later conceded was wrong.

Conduct of Victims of Crime Commissioner

Mr Sofronoff likewise made no findings against Victims of Crime Commissioner Heidi Yates who, he said, was subjected to a degree of unjustified public criticism because of a general lack of understanding about what the law required her to do.

During the trial, Ms Yates attended court with Ms Higgins and her attendance was noted by the media.

“The conspicuous presence at the side of a rape complainant of a public officer whose duty it is to support ‘victims’ of crime led many public commentators to question whether the Commissioner’s actions were prone to prejudice the presumption of innocence to which Mr Lehrmann was entitled.

“Yet, one of the ways in which the Victims of Crime Act permits victims to be supported is by the attendance at court of a representative of the Commissioner’s office, not excluding the Commissioner herself,” Mr Sofronoff said

“It seems to me that, having regard to the way in which this matter unfolded, both in the conduct of the police and lawyers and the actions of media outlets, it was inevitable that the person assigned by the Victims of Crime Commissioner to aid Ms Higgins under the statute would become a fixture until, at least, the conclusion of the trial.

“The Commissioner’s presence at Ms Higgins’ (speech after the jury was discharged) was unfortunate because of the impression it made but it was due to no fault of her own. Her attention was upon her duty to Ms Higgins.

“I have found that a combination of circumstances which were not of her making put her into a spot which implied that she was endorsing a speech by Ms Higgins that was capable of impugning Mr Bruce Lehrmann’s entitlement to a presumption of innocence.

“Her sole purpose at that time, consistently with her statutory duty as well as with human decency, was to ensure, so far as she could, the wellbeing of her client. It was natural and right for her to think and act this way.”