‘Those statements were false’: prosecutor grilled on stand

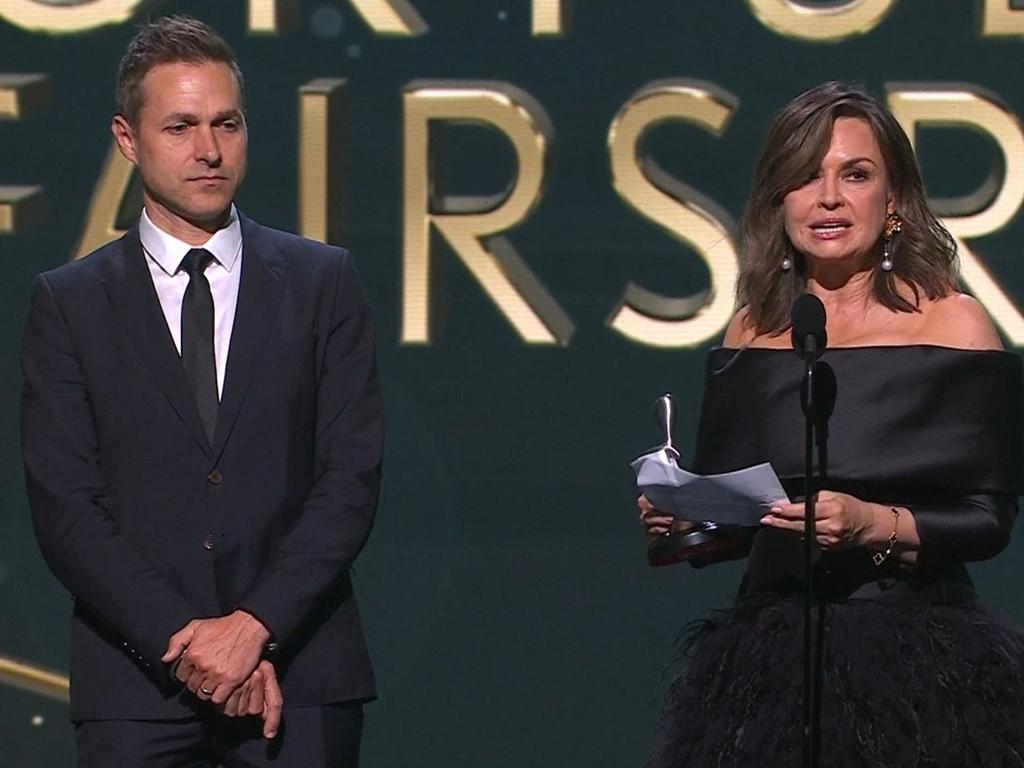

The chief prosecutor in Bruce Lehrmann’s rape case has been accused of making false statements in a hearing over Lisa Wilkinson’s controversial Logies speech.

The chief prosecutor in Bruce Lehrmann’s rape case has been accused of making false statements to trial judge Chief Justice Lucy McCallum in a hearing last year over Lisa Wilkinson’s Logies speech.

ACT Director of Public Prosecutions Shane Drumgold appeared on Monday as the first witness to a special inquiry into the case, headed by Walter Sofronoff KC, facing intense scrutiny over whether he properly disclosed relevant material to the court and the defence.

New documents emerging from the inquiry also reveal the extent to which crucial police documents questioning Brittany Higgins’s rape claims were withheld from defence lawyers.

Just over an hour into the first day, counsel assisting, Erin Longbottom KC, accused Mr Drumgold of making a false statement to Chief Justice McCallum during an stay application to halt proceedings sought by Mr Lehrmann’s lawyers after Wilkinson’s Logie speech last June.

“Those statements were false,” Ms Longbottom put to Mr Drumgold. “They were knowingly false.”

The accusation levelled at Mr Drumgold in the inquiry concerned a contemporaneous note taken during a meeting between Mr Drumgold, two of his junior staff and Wilkinson and her lawyer. Wilkinson had been expected to be a witness at the trial and was being “proofed” – that is, made aware of what would be expected of her when she gave evidence.

The inquiry heard that the note drafted by a junior solicitor, Mitchell Greig, was altered the day before the application to cease proceedings brought by Mr Lehrmann’s lawyers, and after Wilkinson delivered her Logie speech, and other media commentary around her speech.

On the Monday morning after the Logies, Mr Drumgold first advised Mr Greig that the original unaltered proofing note “Looks fine to me”. Six minutes later, Mr Drumgold sent additional words to Mr Greig about his advice to Wilkinson.

The proofing note was later altered to include the copy and paste parts from Mr Drumgold’s email.

This was critical to the application being heard by the Chief Justice, as it recorded Mr Drumgold’s claim that he had stopped Wilkinson from reading her proposed Logie speech to him. “We are not speech editors,” Mr Drumgold said, which was added to the proofing note, along with seven extra lines from the DPP. This altered proofing note was sent to the defence team that afternoon.

When Mr Drumgold was asked in court the next day by the Chief Justice who was responsible for the proofing note, and whether it was contemporaneous, Mr Drumgold told the Chief Judge that his junior solicitor wrote the proofing note and it was contemporaneous.

Commissioner Sofronoff put to Mr Drumgold this was not a contemporaneous note and the cut and paste part tbeing discussed in court by the Chief Justice was not written by his junior solicitor.

“Mr Drumgold, those statements were false,” Ms Longbottom said in court.

Mr Drumgold replied: “No, I don’t accept that they were false.”

Ms Longbottom continued: “And they were knowingly false.”

Mr Drumgold did not accept that.

Mr Sofronoff asked who made the note and Mr Drumgold said it was “made on my contribution”.

“So the answer [to the court], that Mr Greig made that note is not true. It’s false,” Mr Sofronoff said.

Mr Drumgold replied: “Unintentionally, I think so.”

“How can it be unintentional?” Mr Sofronoff asked.

Mr Drumgold said: “Because I hadn’t dissected the note down into its constituent path … Well, I accept that. I was probably an error.”

After some back and forth, Mr Drumgold agreed with Mr Sofronoff that the proofing note was not contemporaneous and that the critical part was not written by his junior solicitor, but had in fact been added at his request the day the application was first sought by Mr Lehrmann’s lawyers, on June 20 last year.

Mr Drumgold also accepted inquiry criticism that he had failed to advise Wilkinson properly.

“She (Wilkinson) was asking for you as the chief prosecutor in the territory to advise her whether in substance the trial would be jeopardised if she said in public what she read out to you? She was asking for your guidance on whether the trial would be jeopardised, wasn’t she?” Ms Longbottom said.

Mr Drumgold said “in hindsight, I should have listened more intently to the speech”.

Mr Sofronoff asked the Chief Prosecutor if he saw it as no part of his function to say to somebody in Wilkinson’s position that she should not make the speech and that it might jeopardise a trial.

Mr Drumgold said he thought he had exercised that function in telling her that any publicity could give rise to a delay or ceasing of court proceeding.

These failures by Mr Drumgold, as described by Ms Longbottom, form only one part of claims against him in this inquiry. Previously unseen documents released by the inquiry on Monday raise new questions about Mr Drumgold’s conduct in the case, particularly in his duty to disclose all relevant material to the defence, as required by law, and his release of unredacted material under Freedom of Information laws to selected media outlets.

The Moller reports

The relationship between the DPP and the Australian Federal Police deteriorated rapidly as the latter progressed their investigation of Ms Higgins’s claims.

Despite his involvement in the case as chief law officer of the ACT, and the national publicity that the rape allegation had received, Mr Drumgold claims it was “unusual” for senior ranking AFP officers to be involved in briefings. He regarded briefings by them as trying to influence his advice as to whether to prosecute Mr Lehrmann.

On June 21, 2021, Mr Drumgold was handed a police brief that described Ms Higgins as “evasive, unco-operative and manipulative” and concluded: “Investigators have serious concerns in relation to the strength and reliability of her evidence but also more importantly her mental health and how any future prosecution may affect her wellbeing.”

The AFP brief was part of a bundle of documents called the Investigative Review Documents, known informally as the Moller report after one of the officers in charge of the investigation, Detective Superintendent Scott Moller.

The existence of the Moller report was first reported in The Australian in December, which revealed that senior police officers on the Higgins case believed there was insufficient evidence to prosecute Mr Lehrmann but could not stop Mr Drumgold from proceeding because “there is too much political interference”.

The full Moller report, now released by the inquiry in Steven Whybrow’s statement, catalogues dozens of discrepancies and “identified issues” in Ms Higgins’s evidence, among them whether she was as drunk as she claimed on the night of the incident, whether she had any romantic interaction with Mr Lehrmann earlier at the 88MPH bar, the placement of her dress when found the next morning by security guards, her repeated failure to hand over her phone to police and questions about the provenance of a photo she claimed to have taken of a bruise caused during the alleged assault.

Mr Drumgold thought the police brief was evidence that investigators were attempting to undermine the investigation.

“I regarded the contents of the documents … as being an attempt by senior police officers to influence the advice that I was asked to give them. In my experience, I had never seen an attempt such as this,” Mr Drumgold said in his statement to the inquiry.

He agreed during questioning that under the court rules of disclosure, police documents prepared as part of their investigation must be handed to the defence.

Ms Longbottom asked Mr Drumgold why that rule of disclosure existed.

“Well, because it has to facilitate interrogation of both inculpatory and exculpatory factors, and factors that I can’t foresee that someone else might be able to foresee,” Mr Drumgold replied.

Yet as the trial approached, the defence team was unaware of the Moller report’s police briefs revealing their serious concerns that there was insufficient evidence to prosecute Mr Lehrmann.

While his first lawyers at Legal Aid had been notified about these documents in the Disclosure Certificate they received, when Mr Lehrmann hired new lawyers – Kamy Saeedi Layers – these documents were not disclosed in the Disclosure Certificate given to them.

Mr Saeedi discovered the documents were missing from the brief handed to them only when he laid the earlier Disclosure Certificate, given to Legal Aid lawyers, side by side with a later copy and realised it didn’t match.

The most recent certificate had been altered to delete any reference to the investigative review document. Nor had “Investigative Review Document” been added to the list of documents that were marked not to be disclosed because of legal professional privilege. It had simply disappeared.

In his statement to the inquiry, Mr Drumgold said: “I am not aware how there came to be two disclosure statements, both apparently dated identically.”

On Monday, Mr Drumgold claimed the investigative review documents were put in two places in the first Disclosure Certificate, but removed from one because the AFP said they were privileged.

Mr Lehrmann’s lawyers immediately issued a disclosure request but were stonewalled by the DPP at every turn.

While Mr Drumgold says in his statement that he “was not involved in all aspects of disclosure in the Lehrmann case”, numerous emails and file notes attached to his statement suggest that he instructed his junior staff that the investigative review documents were privileged and not disclosable to the defence.

In June 2022, Mr Drumgold responded to a request for advice from the AFP by claiming the documents were privileged.

“I considered the investigative review documents were preparatory to confidential communications between the ODPP and the AFP for the dominant purpose of providing legal advice and were therefore not disclosable,” Mr Drumgold said in his statement.

The protracted dispute over disclosure, which continued for three months, spilled over into the courts.

At a hearing on 8 September 8, 2022, Mr Drumgold claimed the document had originally been listed on the disclosure certificate “in error” and that was why it was removed. In court, Mr Drumgold said: “It is the AFP’s legal professional privilege and it is not an issue for us.”

His statement records that during the court stoush, Mr Lehrmann’s barrister, Mr Whybrow, contacted Superintendent Moller, who informed him that the documents were not prepared for legal purposes and that they had no objection to them being handed over.

Eventually, the AFP supplied the documents directly to the defence after a subpoena was issued, noting “the stated intention of the originators of the documents was that they were not created for the purpose of obtaining legal advice, but to obtain a decision from the Deputy Chief Police Officer”.

In his statement, Mr Drumgold said “I formed the view that DS Moller actively wanted to disclose to the defence, his commentary including his perceived weakness in the case.

“This appeared to be a further example of what I perceived as ongoing assistance to the defence.”

Mr Drumgold did not provide evidence of why the documents were not disclosable, given DS Moller had said their documents were not prepared for the purpose of legal advice.

When Mr Sofronoff put to Mr Drumgold that whether legal professional privilege applies to these police documents was a matter of fact and to be determined by the state of mind of the author of the document, Mr Drumgold responded: “An inquiry is being made of me.”

Mr Sofronoff: “Correct. You’re a barrister. I would expect that in order to answer the question, you’d need some facts, and you don’t seem to have any facts, Mr Drumgold.”

Mr Drumgold: Effectively what I’m saying there is, based on the timing, I considered them to be subject to legal professional privilege.

“Now, if they consulted widely as they did and got an alternative view on their dominant purpose for them, they were free to find that.”

Part of the Moller reports received by defence lawyers was an investigation review dated August 3, 2021.

Superintendent Moller had sent the police brief for “a tactical investigative review” to be carried out by Commander Andrew Smith and three other officers, none of whom was involved in the original investigation.

The review team found “that the investigation was conducted in a thorough, reasonable and proportionate manner, adhering to the lawful requirements for interviewing suspects and witnesses.

“The investigation team applied a critical and analytical mindset to the material which identified their avenues of inquiry.

“The review team did not identify any significant additional avenues of inquiry.

“There is nothing to suggest the investigation was inadequate or unprofessional.”

Mr Drumgold does not mention the Smith review in his statement to the inquiry.

The Brown complaint

Another disclosure issue for Mr Drumgold concerns Fiona Brown, chief of staff to minister Linda Reynolds at the time of the alleged offence. Ms Brown was an important witness in the trial.

Ms Higgins had alleged she was pressured by Ms Brown and Senator Reynolds not to pursue the alleged assault, in the context of a looming federal election, but her claim was vigorously rejected by both women at the trial.

The Australian has previously revealed how Ms Brown accused Mr Drumgold of threatening and intimidating her after she left the witness box on a morning tea break, and of ignoring her pleas to be recalled to the stand to refute “blatantly false and misleading” evidence by Ms Higgins.

In a formal complaint to the ACT Bar Association, Ms Brown said Mr Drumgold and an associate berated her for providing “inadmissable evidence” and that Mr Drumgold then tried to use her mental health to discredit her as a witness.

Ms Higgins had told the court that Ms Brown offered to pay her six weeks’ wages to go to the Gold Coast with no prospect of her returning to work after the election.

Ms Brown emailed the DPP saying that simply did not – and could not – happen. “Neither Minister Reynolds or I had the authority to pay any staff member out. And I did not at any time state or suggest this” Ms Brown wrote.

“I am deeply troubled by this serious misrepresentation in proceedings and I seek to have them corrected or put to me in court,” she requested.

Ms Brown says she did not receive a response to her request to correct the record.

In his statement to the inquiry, Mr Drumgold rejected Ms Brown’s contention as “without substance”.

“I was confident the defence and jury were aware of Ms Higgins’s initial evidence on the issue and its import, and were aware of Ms Brown’s differing account.”

Mr Drumgold also said he “did not consider Ms Brown’s email raised any issue requiring disclosure to the defence”.

Consequently, Mr Lehrmann’s legal team was never alerted to the complaint and had no opportunity to decide whether it wanted to recall Ms Brown to raise the inconsistency in front of the jury.

Mr Drumgold said he had not received notice of the outcome of the complaint to the Bar Association.

The fast FOI approval

The inquiry is also expected to closely examine Mr Drumgold’s decision to release under FOI his unredacted letter of complaint to ACT police chief Neil Gaughan only hours after The Guardian newspaper applied for it.

Mr Drumgold describes receiving a phone call from Guardian journalist Christopher Knaus on the morning of December 3, 2022, asking whether he had seen the Moller report article in The Australian.

“I was confronted by a clear and what I considered to be an unfounded inference that I had committed misconduct in my office by directing police to lay charges in an unmeritorious case due to political pressure that was supposedly exerted on me,” Mr Drumgold said in his statement to the inquiry.

“I did not draw any firm conclusion as to how material from the 4 June, 2021, minute came to be in the possession of The Australian, but felt that the source could realistically only be the AFP or the defence, as aside from the ODPP, these were the only parties who, to my knowledge, were in possession of that document.

“I felt highly emotional at the personal attack and the unfounded accusations of misconduct that I felt had been made against me, and felt a sense of absolute devastation.

“I had never been the subject of such a malicious, serious and unfounded personal public attack before.”

On December 7, 2022, at 3.06pm, Mr Drumgold received an email from his information officer, Katie Cantwell, attaching the FOI request and expressing her view that the documents were “likely to be subject to legal professional privilege”.

At 6.35pm, Ms Cantwell emailed him, asking whether “this is the letter you are happy for me to release under FOI to the Guardian?”

Drumgold responded 15 minutes later: “I am happy for it to go out”.

Ms Cantwell emailed the letter to Mr Knaus that evening without any redactions.

“When sending that email. I had not given it due thought,” Mr Drumgold conceded in his statement to the inquiry.

“I acknowledge that my response to Ms Cantwell risked being interpreted, as it subsequently was, that the letter was to be sent out without further consideration of other relevant FOI considerations.”

Two days later, the ODPP sent a redacted version of the letter to The Guardian that removed all names of parties, except that of Mr Whybrow.

Mr Drumgold failed to explain in his statement why he continued to deny access to the letter to all other media outlets for several days. In response to repeated requests from The Australian and others for a copy of the letter, it was finally made available five days after its release to The Guardian.

It was in that letter to Gaughan that Mr Drumgold asked for support for a public inquiry.

That inquiry, called by the ACT government, will see Mr Drumgold questioned further over the course of this week by a host of lawyers, including Ms Longbottom and lawyers acting for the AFP, Mr Whybrow and for Wilkinson.