Six ordinary Australians who did extraordinary things to save Australia during World War II

Listen to their stories, cherish them, because we’re down to the last, hardy survivors of the 900,000-plus Australians who pulled on a uniform when the world went to war in the bloodiest conflict in human history.

They’re a bonza bunch, aged 97 to 105, amazing Australians all. They saw the country through the darkest time it ever faced in World War II and built a future that every single one of us can be thankful for.

They’re among the last of their great generation and here they are, together in their twilight years, enjoying each other’s company and the warm Melbourne sun ahead of Anzac Day.

Some of their lives have intersected over the decades; others met after entering Vasey RSL Care at Brighton, where the staff are inordinately proud to look after six of Australia’s few remaining WWII veterans.

There’s Ralph Butcher, 105 and counting, still lively, still dining out on how he became a captain in the British army after Australia turned him away. His parents were missionaries, you see, and there was the complication that they had lived in New Guinea among practising cannibals and sent him to boarding school in England. It’s quite a tale.

Betty Cooper, 101 in August, nursed the sick and wounded who fought the Japanese to a standstill on our northern doorstep and became a casualty herself. She was invalided home from New Guinea with a lifelong spinal injury.

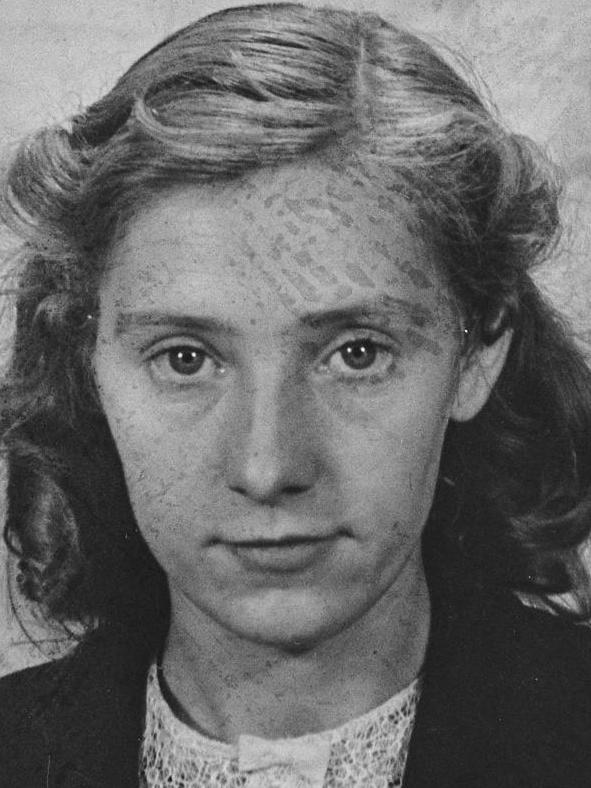

At 97, Audrey Baker remembers the camaraderie of her sister WAAAFs in Hut No.7 of the sprawling air force headquarters in Albert Park, Melbourne. They were bonza, too. “Make sure you use that word,” she said, laughing. “You don’t hear it these days.”

Annie Overs, 101, joined the RAAF in 1942 because her brother, Mick, and Uncle Bob were air force men. Her war was mostly spent in the catering mess at the big air base in East Sale, Victoria: it was hard, thankless work, but she is proud to have done it for her country.

For Marie Laurenceson, 98, becoming a signals clerk in the RAAF at 18 was the natural thing to do when her father, Joseph, had slogged through the WWI killing fields of Gallipoli and the Western Front. She vividly remembers how the family would host lonely young Diggers who had nowhere else to go before being deployed to a far-flung theatre of World War II.

A fellow named Laurie spent his visit reading the Bible. “I later heard he was killed,” she said. “He probably spent that time with us thinking about what could happen when he went to war.”

Frank Bristow, 98, was having an off day, confined to bed when The Australian visited. The RAAF veteran doesn’t like to talk about his job on the ground staff of a unit responsible for anti-aircraft batteries and air-to-air fighter interceptions across what’s now the Indonesian archipelago.

“Israel is more interesting at the moment,” he said.

Honouring the heroes of World War II

Listen to their stories, cherish them, because we’re down to the last, hardy survivors of the 900,000-plus Australians who pulled on a uniform when the world went to war between 1939 and 1945 in the bloodiest conflict in human history.

It was the first and only time the homeland was threatened directly as the Japanese advanced relentlessly through the Indo-Pacific, conquering Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, Burma and most of the Solomon Islands before being checked by the US Navy at Midway and by Australian troops at Milne Bay and on the Kokoda Track in modern-day PNG.

The last of the greatest generation

The WWII generation is fading fast: by July 1, there will be fewer than 2500 of them left, a number that has halved in two years. The veterans’ ranks will halve again by the end of next year and is projected to dip to just 800 in 2026. By then, their average age will be 101.5, up from 99.6 today.

Three of the Vasey Six live on the same corridor of the quiet residential care home in bayside Melbourne: Ralph, Marie and Audrey, which seems fitting given how the war shaped their lives.

Well, he would have to wait at least six weeks for a ship home, and the voyage would take another month and could be dicey when the German navy was on the prowl. “They told me it might be better to join the British army because that was the fastest way to get into it, so I did,” he said. “But … it wasn’t my first choice.”

His missionary father had instilled quite the spirit of adventure in young Ralph, though he didn’t believe in killing. Ben Butcher had seen too much of that as a padre in the WWI trenches. The family had lived in a hut he built by hand on the Kikori River in southern Papua, among the exotic-looking tribespeople who persisted in eating their enemies when Ben first encountered them.

After being selected for specialist officer training, Ralph was posted to the Royal Army Ordnance Corps to trail the frontline units and scour captured, abandoned or valuable battle-damaged enemy equipment.

In North Africa, he scavenged prized optical sights from the smoking wreckage of German panzers. He was in a convoy bound for Greece, towards the end of the war, when one of the transport ships struck a sea mine and capsized. He had been urging the crewmen who had climbed onto the overturned hull to swim for it, when a companion said gently: “Ralph, they’re British, not Australian. They don’t know how.”

Back home in Melbourne, he helped found the Beaumaris Legacy Widows Club, where he encountered Marie at one of the meetings. They struck up a lasting friendship. “Ralph was always a gentleman,” she remembers. “He did a lot for Legacy; he still does.”

She and husband Bert, an RAAF man, raised a family of two daughters that now numbers four grandchildren and nine great grandchildren. Marie and Ralph still swap news when they catch up in the breakfast room.

Audrey remembers the bland, wartime fare of tinned bully beef and cabbage, and how the girls in Hut 7 knew better than to complain when the troops in the islands were lucky “to get tea and cigarettes”. She joined up on her 18th birthday in 1944 and met her husband, Edward, not long after the Japanese threw in the towel.

He was a gunner in the artillery whose leg had been shattered by a sniper’s bullet on Bougainville, and returned home weighing barely 38kg, racked by malaria. On one of their first dates, he passed out in the cinema and the sailors sitting behind them took charge, saying kindly: “We know what’s wrong with him.”

Audrey didn’t remarry after Edward died of lung cancer in 1961, aged only 41. The poor man never got over the war, she said. He tried and tried, but he would become “morose” and take long, lonely push bike rides to Geelong.

“He was grey at the temples when he came home,” she recalled. “He had the feeling that he had lost so much out there, in the war. He was like a lot of the other men … he just couldn’t get over that feeling of loss … it was a weight he carried with him and in the end I think it killed him.”

Betty hates to think about the possibility that any of her nine great grandchildren could have to endure the hardships and heartache her generation did in WWII.

The memory of the horribly hurt and ill soldiers she nursed in New Guinea – before being laid low by a swimming accident – haunts her to this day.

A few years ago, she had four vertebrae surgically fused to relieve the grinding pain.

“I don’t like to talk about my army experience very much,” she said. “I feel if I do, it sort of glorifies war and I don’t want to do that after seeing what I did, knowing how cruel it is.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout