But it has little to do with Donald Trump.

Two other significant adjustments were beginning to occur before the conservative political realignment in the US.

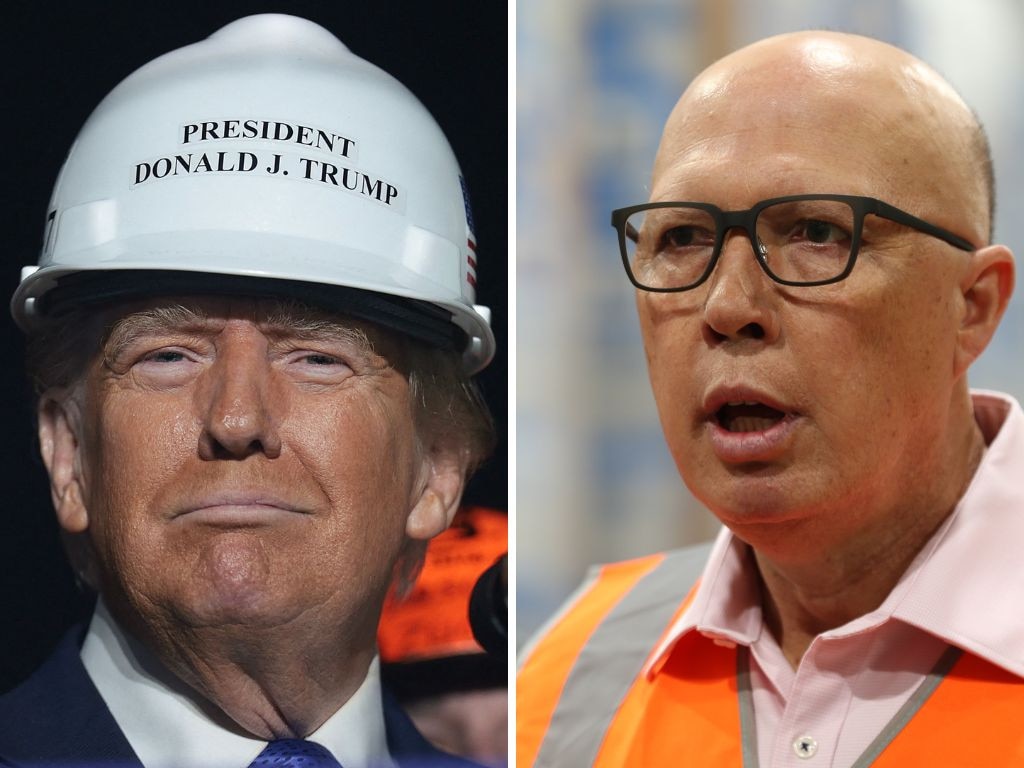

The first is the new domestic economic assessment. The second is the evolving assessment of Peter Dutton.

The likelihood that there may now not be an interest rate cut before a May election now threatens to disrupt the Albanese government’s preferred orthodoxy on inflation and spending.

As a consequence, it has severely degraded Labor’s strategic options.

Failure to elicit a rate cut will diminish Labor’s ability to campaign around a theme that, through its management, economic conditions had turned.

If anything, by the time of the election, living standards will have fallen further.

If Jim Chalmers has come to the same conclusion as the markets have about rates, there will be nothing for Anthony Albanese to wait for – he might seek to go to an earlier election.

The economy has boxed Labor into a corner because they got it wrong by underestimating how hard it was going to be to beat the inflation problem, despite attempting to get the settings right.

There are already signs of the shift in Labor’s thinking.

If the $20bn student loan relief plan is any indication, the government has already made the decision that in the absence of a rate cut, the only way it can appeal to voters is by spending more.

The Opposition Leader is convinced of this. Having been left with few options, Labor will simply open the pipes on spending.

What that will do to inflation and interest rates after the election will become an election issue.

Hope is fading of a cut to rates before the election and this will continue to dawn on people over the coming weeks.

This becomes a significant problem for the Prime Minister in trying to frame the election narrative. What will it be?

The second shift is equally challenging for Labor, and one that was not anticipated.

Dutton has managed to restore the Coalition to a position of electoral competitiveness. His approval ratings are now better than Albanese and there is little between the two leaders as to who voters prefer as prime minister. At the same time, the Coalition’s primary vote has been restored to a competitive level at 40 per cent.

Few on the Coalition side believed that considering the low base it was working from following the last election, they would be in this position months out from an election.

Even fewer on the Labor side would have seen this coming.

The Coalition’s economic narrative is so far unrefined. But Dutton has now assessed that inflation will still be the single most important fight.

It leaves everything else for dead. Including, it would appear, tax cuts.

The interpretation of Dutton’s remarks this week are that he has walking back tax cuts. This is not the case. The question for Dutton will be what can the Coalition afford in the budget, which will depend largely on Labor’s spending profile, and the potential inflationary effect.

There are still plenty of ways Dutton can frame a tax-cut package, including the more likely scenario of staging them beyond the critical inflationary period.

The Coalition is still committed to tax cuts in some form. What Dutton has signalled this week is that they will be a secondary issue to the primary battle over falling living standards under Labor.

The Coalition-dominated Senate select committee on cost of living, released on Friday after two years of inquiry, points to where Dutton intends to take the election contest.

Labor’s spending commitments between now and the campaign will be in much sharper focus. Dutton’s success lies in whether he can convince voters of the link between government spending and the conditions that continue to make life harder for them.

The domestic political ground has fundamentally shifted over the past few weeks.