Re-elect PM? Turns out some weren’t so Kean

It was less than two weeks from election day when Matt Kean, the second most senior Liberal in NSW, inserted himself into the campaign against Scott Morrison’s re-election.

It was less than two weeks from election day when Matt Kean, the second most senior Liberal in NSW and the state’s Treasurer, inserted himself into the political campaign against Scott Morrison’s re-election.

Kean shot a message to a young journalist on the road with the then-prime minister, encouraging her to ask questions around the political controversy over Katherine Deves. The Warringah candidate had backtracked on her apology over comments about transgender children being “surgically mutilated’’ the night before in an interview with Sky News host Chris Kenny.

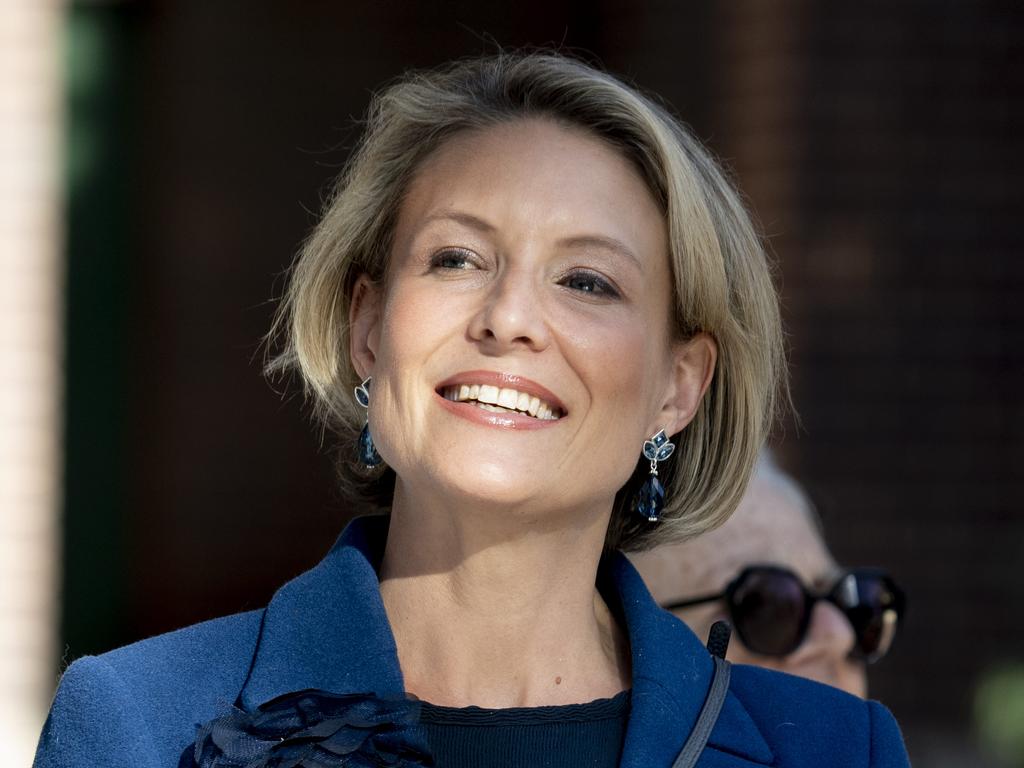

Kean, 11 days out from polling day, messaged the Ten Network’s Stela Todorovic, urging her to ask questions about the issue.

Morrison was standing with Liberal state minister Natalie Ward announcing an extension of the Epping Road Bridge in Sydney’s north.

Kean pushed Todorovic to draw Ward into the furore over Deves, who was lying low on the orders of the national campaign.

“We definitely pushed it along. I tried to get Natalie on it – and she seemed keen to chat but Morrison ended the presser and she was forced to leave,” the reporter wrote to the Treasurer over Twitter’s Direct Messaging platform.

“You should pap her,” Kean responded, according to photographs of the exchange seen by The Weekend Australian.

News that Kean, who declined to comment, was encouraging journalists to pursue the issue made its way to the prime minister and his senior team.

They were astounded that one of the most senior figures in the NSW Liberal government was trying to sabotage Morrison’s election prospects. While Labor premiers Mark McGowan, Annastacia Palaszczuk and Daniel Andrews were campaigning to help Anthony Albanese win, a top politician from one of only two state Liberal governments was seemingly working against the prime minister.

Kean had been leading calls for the Liberal Party to disendorse Deves. His stance was at odds with that of Premier Dominic Perrottet, who sent Morrison a text message on the weekend of April 16 to offer his support on the substantive issue of women competing against women in sport.

Morrison’s principal private secretary, Yaron Finkelstein, phoned Kean that day, but he missed the call. They finally spoke the following morning and it is understood Finkelstein said he had become aware of Kean’s contact and messages with journalists.

A second source close to Morrison raised the issue separately with Kean, who strongly denied the allegation and claimed he was doing everything in his power to help Morrison’s re-election.

Liberal rivals

There was no love lost between Kean, the leader of the moderate faction in NSW, and Morrison.

Kean had reinvented himself as a green warrior championing action against climate change and more renewable energy after a major personal crisis. He had fretted whether his political career was over after an ex-girlfriend leaked messages he had sent to a female MP, propositioning her for sex. His ex-girlfriend worked for prime minister Malcolm Turnbull at the time.

While Kean and Turnbull had an acrimonious start to their relationship, the Treasurer has confided to friends that the pair worked through their differences and were in contact.

The 40-year-old first spoke publicly against Morrison in February 2020 when he told this author on Sky News that some of Morrison’s senior cabinet ministers wanted him to take stronger action on climate change.

Mr Morrison retorted the next day: “Most of the federal cabinet wouldn’t even know who Matt Kean was.”

The remark, reported widely, ironically elevated the little-known MP’s profile.

As the years went on, the animosity between the pair grew. But the war Kean waged against Morrison was ultimately self-defeating. Many of his moderate colleagues would end up losing their seats, including his close friend Trent Zimmerman and federal treasurer and potential future prime minister Josh Frydenberg.

The wipe-out of ambitious and talented Liberals in blue-ribbon seats delivered Peter Dutton the Liberal leadership and has given Kean’s rival conservative faction the power and the numbers in Canberra.

On the surface, Morrison was battling Labor and the teals during the election campaign, but he was also facing division from disgruntled Liberals.

Liberal senator Andrew Bragg, who worked with pollster Crosby Textor during a short period at the federal Liberal Party before entering the Senate in 2019, was one of the strongest internal dissenters. During the campaign, Bragg was vocal about his distaste for the way Morrison had operated as prime minister, describing him to colleagues as unprincipled.

“If he wins, he will need to change the way he operates,” Bragg said during the campaign.

He was angry and freely expressed his view that Morrison would cost moderates, such as Frydenberg, their seats. Bragg was a strong supporter of Frydenberg and was canvassing support for him to take over the opposition leadership after the election.

As such, he was not awarded a frontbench position in Dutton’s shadow ministry reshuffle.

Political strategist Isaac Levido, credited with Boris Johnson’s 2019 win, was working in the Coalition’s Brisbane campaign headquarters and, as a close friend of Bragg, was chosen as the emissary to try to pull Bragg into line on several occasions during the campaign.

“They sent him out to talk to me when they wanted to send a message,” Bragg says.

“They didn’t want me to talk about the transgender issue, but I said if I was asked I would give an honest answer because I didn’t agree with Morrison’s position.

“They also didn’t want me to speak about expanding the superannuation policy, opening up super for mortgages and other things. That was the final week of the campaign and I agreed in general terms not to inflame things.”

In the final week of the election campaign, The Australian’s columnist and Ten reporter Peter van Onselen claimed to have “leaked internal Liberal polling” that showed the Liberals were on track to lose three NSW seats: Reid, Bennelong and Parramatta. He also said Deves was “still in the hunt to win the seat” of Warringah with a two-party-preferred vote of 47 per cent to Zali Steggall’s 53 per cent. It was the second set of polling van Onselen had broadcast.

Senior Liberal figures scratched their heads, wondering where it had originated. The precise numbers did not reflect what was emanating from the party’s official poster, Crosby Textor.

An internal probe discovered that Bragg had submitted expenses to the NSW Liberal division of about $35,000 to $40,000 to conduct his own alternative polling in many NSW seats.

There is no suggestion that Bragg leaked the polling to van Onselen, which he denies. It was not in his interest to depress the prospects of candidates he was fighting hard to help win.

It’s not even clear whether the polling Bragg commissioned was the same polling broadcast on Ten. However, Morrison’s team believed it was.

Bragg had circulated the polling he commissioned to many Liberals – an action one source described as “sloppy” – and the suggestion is a recipient subsequently leaked it to the media.

Questioned about the research for this article, Bragg admits he commissioned alternate polling and is scathing about the way Liberal headquarters and Crosby Textor treat Liberal candidates, who he says are kept in the dark about how they are faring.

“The Liberal Party and Crosby Textor treat the candidates like absolute shit and don’t give them the information they need,” Bragg says. “The candidates, who are often members of parliament, all they are given is a phone briefing and if they’re lucky they might get a piece of paper. Crosby Textor omit key things like the favourability of the leader because they’re worried that will leak to the media. If you know the party leader is massively unpopular you’ll differentiate so you can hang onto the seat. But if you’re not told that how are you supposed to know? It’s conflicts galore.”

Battle for Wentworth

In Wentworth, Bragg’s robo-polling during the campaign showed Dave Sharma was on track to win his seat with a primary vote in the high 40s. Crosby Textor’s polling painted a vastly different story, showing Sharma’s primary was about 38 per cent, closer to the 40 per cent he achieved.

“In our mind we needed 43 or 44 at least to win and the CT track never had us there,” a Wentworth insider said.

Another internal Liberal source said Bragg’s alternate research had the effect of giving Sharma false confidence his position was stronger than the reality.

“When you start having duelling polling wars going on and different methodologies, that’s never helpful,” a senior Liberal said.

There was also a sense the published polls got it wrong in 2019 and Sharma was encouraged by the positive reception at pre-polling booths. “It feels more like 2019 than 2018,” he said during the campaign, referring to the by-election he lost to Kerryn Phelps in the wake of the federal leadership spill in late 2018.

While Sharma and Bragg remain good friends, others involved in the Wentworth campaign want to ban him from interfering in future elections by muddying the waters with conflicting research.

The alternative polling was “inevitably described as ‘official’ polling and had the effect of creating overly pessimistic or overly optimistic result scenarios and impacted upon subsequent campaign activities, fundraising and momentum”, says the Wentworth FEC submission being prepared for the Liberal Party election review led by Brian Loughnane.

It recommends: “No longer allow patron senators to commission polling, research or demographic data analysis without the specific approval of the relevant state director.”

Bragg says he commissioned the research not only to give candidates more information but to guide which seats he should invest in from the $350,000 he had fundraised for the NSW division of the Liberal Party.

“Obviously if I’m going to spend $300,000 on an election campaign from money I’m raising from people, a lot of dinners and lunches, you want to make sure you’re going to put that money into seats where you have the best chance of winning,” he says.

Bragg, who was flatmates with Sharma and former Reid MP Fiona Martin in Canberra, is also blamed for encouraging Martin to cross the floor on the religious freedoms legislation, which he didn’t support. Bragg strongly urged Sharma to cross the floor.

Martin was the only MP not to afford Morrison a heads-up that she wouldn’t be supporting the government’s bill – a betrayal that was held against her.

Senior campaign sources say the move cost her the otherwise cohesive Maronite Christian vote in her electorate. It’s understood Archbishop Antoine-Charbel Tarabay let it be known he was disappointed in her actions.

The Prime Minister’s unpopularity was certainly a factor in seats won by the teal independents.

In Wentworth, Sharma’s favourability was plus 13 while Morrison’s favourability was negative 26, according to polling in the first week of May.

Albanese was the preferred prime minister in Wentworth on 50 per cent, while Morrison had the support of 35 per cent.

In the wake of the election, Morrison has expressed an idea to some of his confidants about a possible strategy to deal with the independents in future elections: establish the Liberal National Party brand Australia-wide as the main conservative political movement.

Instead of the Nationals being the Coalition partner, he has suggested setting up a new progressive Liberal movement as the Coalition partner. It could run a different brand in the inner-city seats.

Campaign flaws

Aside from Morrison’s unpopularity, particularly with female voters, there were other major structural issues with local campaigns.

An excerpt from a draft submission by party officials to the Liberal campaign review, obtained for this article, claims there were a number of first-term MPs who ultimately lost their seats after they “failed to meet minimum benchmarks for community engagement and voter contact either through traditional doorknocking, direct mail or social media”.

The recommendation is that new MPs and senators need to undertake formal training by political professionals.

There was also the problem of inadequate candidate vetting. External agencies were hired to vet candidates including Deves and the Liberal candidate in the Victorian seat of Scullin, who came unstuck amid controversy around his real estate business.

The extent of Deves’s controversial remarks on the transgender issue was not discovered during the vetting process. While the external agencies employed had a good record of vetting board appointments, they underestimated the scrutiny political candidates would be subject to.

In Wentworth, campaign officials decided they couldn’t compete with independent Allegra Spender’s enthusiastic team of volunteers who were putting corflutes up around the electorate. Instead they tried to get Ausgrid to force her to pull them down, in accordance with the law.

“A view taken was because we couldn’t match the volume of her corflutes, getting Ausgrid involved evened the playing field,” a campaign insider said.

This didn’t happen and the result was that Spender’s face populated the electorate. Her name recognition rose while Sharma had very little visible presence.

Sharma was also outmatched in volunteers by an estimate of four to one. It was a struggle to staff polling booths from 8am to 6pm during the pre-polling weeks.

Polling shortfalls

The Crosby Textor research may have accurately captured the Liberal and Labor primary vote in most of the seats it tracked, but there is criticism it vastly underestimated the independent vote, severely masking the threat to the Liberals from the teals, and it failed to detect the size of the swing against the Liberals in Western Australia.

The WA research indicated Swan and Pearce were in trouble, but those close to Morrison predicted potentially only one seat would be lost in the state.

They were even hopeful of picking up Cowan, held by Labor MP Anne Aly.

Senior Liberal MP Ben Morton felt relaxed enough about his seat of Tangney that he stopped campaigning in his electorate halfway through the campaign, instead hopping on the Prime Minister’s plane to travel with him, as he had done in 2019.

It was a shock to Morrison on election night when Morton lost his seat. Sources say he felt terrible for both him and former Robertson MP Lucy Wicks, close friends now out of a job.

“It was pretty stupid, to be honest,” one senior Liberal source said of Morton’s move to leave his seat for the travelling campaign.

“To be frank, I don’t think he wanted to do three or six years in opposition as well, so I don’t think he’s too bothered.”

The optimism the Liberal Party had about Western Australia proved to be utterly wrong, with the state recording the biggest swing against the party nationwide. “I don’t think we expected to lose seats like Tangney, Curtin; we didn’t expect Menzies to be as close as it was in Victoria,” a senior source said.

The seats contested by independents were not included in the nightly track, a deliberate decision because the track measured the Liberal-versus-Labor contest.

The seats ultimately won by the teals were instead subject to spot polls at occasional points during the campaign.

Frydenberg was well behind independent candidate Monique Ryan when his seat was polled several weeks out from election day. As May 21 drew closer, it looked like his position had improved.

“I don’t think there was a CT poll that had Josh ahead,” a senior Liberal said. “The assumption was made that he was improving his position and that come polling day people may have been flirting with Monique Ryan but returned to Frydenberg.

“There was a hope that very effective members like Josh and Dave Sharma would get over the line because voters in these seats are sensible.”

The fact the Crosby Textor research underestimated the losses in Western Australia and the impact of the teals gave Morrison more confidence about his prospects on election day.

No Liberal strategists anticipated the Coalition’s seat total to plunge from 76 to 58.

“I wasn’t expecting us to win but wasn’t expecting our seat count to be so low,” a senior campaign source said.

The Liberal Party’s final polling in the 20 marginal seats it was tracking nightly was accurate – just 0.8 per cent out from the two-party-preferred result.

That final tracking poll was 72 hours from the close of polls.

Misplaced confidence

Undeterred, Morrison remained “relentlessly disciplined in his confidence” and upbeat in the final days of the campaign. At that point, there were high hopes at senior levels of the Liberal team that the 5 per cent of undecided voters could fall their way.

Morrison’s confidence was also attributed to how Labor’s primary vote had plummeted in the final weeks of the campaign, according to Crosby Textor research. Morrison’s view was understood to be that Labor couldn’t form majority government with a primary vote that had crashed so low.

At midday on election day, Finkelstein was downcast about their chance of success, confiding to his colleagues that Albanese would win. “He thinks the undecided started to fall the way of change on Thursday night and last night,” a source said at the time.

Federal Liberal campaign director Andrew Hirst was also pessimistic and was bracing for a loss, although not as brutal as the scenario that eventuated.

The prime minister, however, dismissed Finkelstein’s dire prediction.

“Yaron is just tired, he’s exhausted after a long campaign,” Morrison said early in the afternoon to a close confidant.

Those close to Morrison say he was “quietly confident” that he could win minority government; that he could pull off a miracle once again.

On election night, Sky News host Paul Murray was reporting from the Liberal function at the Fullerton hotel in Sydney’s CBD.

He recalls that at the start of the night there was no sense of the scale of the impending defeat.

“There are times when you’re going to lose so everyone walks in going ‘how bad is this going to be’,” he said.

But that wasn’t the mood in the room on election night. Instead there was an initial sense of hope.

“The whole scenario is they weren’t supposed to win last time,” Murray said.

“They all had muscle memory of winning against the trend.

“On election night, everyone saw Labor’s vote was down so they assumed this was happening again. Even in the second hour when it started going against the Libs, they were very much of the view that pre-poll hasn’t been counted yet.

“Then there was the final realisation that the train is not going to arrive.”

At Kirribilli House, Morrison remained hopeful and upbeat as he bundled into his study with his closest friends, advisers and strategists, including David Gazard, Andrew Carswell, Finkelstein, Adrian Harrington and John Kunkel. Morrison sat at his desk, examining the raw numbers as they were coming in from the Australian Electoral Commission.

Outside, Jenny Morrison, ever-positive and smiling, entertained about 20 of the couple’s friends from the Shire.

The first hour looked to be a repeat of 2019, with early polling showing Labor’s depressed primary vote.

Then there was a view in the room, about 7.30 to 8pm, that there wouldn’t be a definitive result that night.

Nail in the coffin

But then it changed.

“The pre-poll voting, which we would have thought favoured us, it just didn’t,” said one source from the room.

“When those results started being dropped, it cemented the trend. And then it changed really quickly.”

Morrison left the room to take a long call from Frydenberg, who a source said was “in a pretty bad way”.

During the half-hour that he was out of the room, the size of the teal problem crystallised.

Morrison walked back in and said: “How is it looking?”

“It’s not good,” an adviser said.

“I know it’s not good,” Morrison replied.

“It’s got worse,” a friend replied.

Then the Mackellar numbers started flowing in. “Jason (Falinski) is in trouble,” Morrison said.

A source in the room said that “when Jason’s results became clear, that’s when hope was abandoned”.

Finkelstein was the one who called it, according to those present. “We will be conceding tonight,” he said.

Not long after that, Jenny and the Morrisons’ daughters, Abbey and Lily, came in and gave the outgoing prime minister a hug.

“It was a night of mixed emotions for Jenny. She had a sadness for Scott but it was tinged with a different emotion, which is that now she will get some sense of normality for her and her girls,” a source said.

Morrison was disappointed but not overtly emotional. Pragmatic, he started working on his concession speech with his team before calling Albanese to concede just after 10pm.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout