Premier needs to ‘step up’ in Koonalda rock art dispute

Scientists banned from the cave because of a dispute between Indigenous groups say it’s time for Peter Malinauskas to get involved.

Scientists barred from the ancient Koonalda Cave in South Australia following a dispute between Indigenous groups say it’s time for Premier Peter Malinauskas to step in and resolve the impasse.

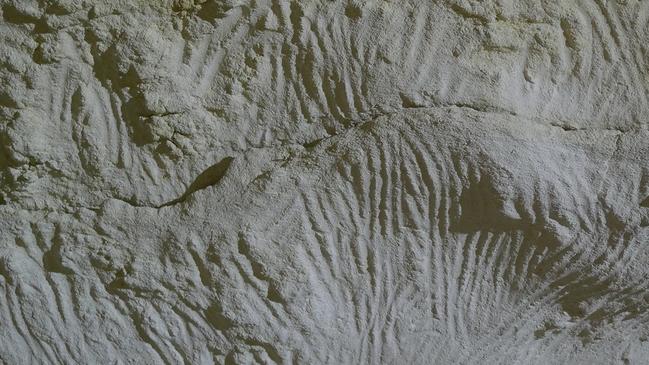

Clare Buswell, the chair of the conservation commission of the Australian Speleological Federation, said that the conflict between “warring government agencies” administering various legislation had in effect left our understanding of the 40,000-year-old cave on the Nullarbor Plain stuck in the 1960s.

“Maybe it’s time for the Premier to step in and do the job his ministers are clearly not doing,” she said.

Dr Buswell worked on the cave, 900km from Adelaide, for several years with archaeologist Keryn Walshe and Canadian researchers, but work was halted in mid-2022 when they alerted authorities to vandalism at the site.

The Australian Heritage Commission gave South Australia $400,000 to protect the cave which has precious “finger flute” engravings said to be unique in the world. It is understood much of the money has been spent on a two-year consultation process led by the state’s Department of Environment and Water and on proposed surveillance cameras at Koonalda. But $85,000 earmarked for research will now be returned unused because the review, which has developed a conservation management plan for the cave, could not resolve a dispute over access.

The native title holder, the Far West Coast Aboriginal Corporation, supports research, mainly the measurement of water and temperature in order to determine how best to protect the fragile limestone. But the Council of Mirning Elders, which was involved in the review as traditional owners, argue it should monitor any research.

Dr Buswell said there was an urgent need to review the SA Aboriginal Heritage Act and the scientific permits process because researchers were often caught between DEW and the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation and the SA National Parks and Wildlife Service.

“There is a need for greater transparency around who grants this permit and the power of its permissions,” she said.

“The conflict that currently exists leaves those wishing to contribute to the knowledge values of the area caught between two warring government agencies, resulting in the view that management by inaction is the best way forward.

“This is an outcome that has meant that understanding the values of the Koonalda Cave has not moved on from the 1960s when Dr Alexander Gallus undertook his ground breaking work. Maybe it is time for the Premier to step in and do the job his ministers are clearly not doing.”

The DEW said last week that during the review “questions were asked regarding aspects of future research proposals” and that “further work is required to reach an agreement addressing those questions. Once addressed, research will be able to continue at the cave.”. A DEW spokesperson said the conservation management plan would soon receive final approval from the Director of National Parks so that cameras could be installed.

Dr Walshe, a freelance archaeologist previously with the South Australian Museum, was originally granted access by the Mirning people, but after native title was decided in 2014, access was via the FWCAC. That is now being challenged by the Mirning group.

Koonalda has been all but ignored by Australian research funders for decades and Dr Walshe’s work has been supported since 2016 by about $200,000 of Canadian government and university money through April Nowell, an archaeologist and professor at the University of Victoria, British Columbia.

Dr Nowell, who has been poised to return to the site for months in anticipation of permits being granted, told The Australian the ban was “heartbreaking”.

“Koonalda is so well known internationally,” she said. “Outside Australia, it’s a site that’s really well known, that’s extremely valued. You say, Oh, I’m looking at Koonalda, and people say, ‘Oh, really!’. Everybody knows the site.”

She said the “finger flutes” were thought to be the oldest associated with humans anywhere in the world: “They’re spectacular because they’re so well preserved, and there are so many of them. As someone who has studied human evolution and rock art, this is an incredibly interesting and important site and one that I’ve been teaching about in my class on rock art for decades.

“I’m frustrated because we put all of our research on hold for more than two years in good faith; we were very concerned about protecting the site right from the very beginning. “What’s so discouraging is that we have an excellent team in place; we have good research questions; we have a wonderful relationship with our Aboriginal research partners.”

Dr Buswell said it was important to place Indigenous rangers on country at Koonalda to educate tourists and afford better protection than security cameras.

An SA government spokesman said Aboriginal people had cared for the cave for tens of thousands of year and it was recognised as an important and sensitive cultural site.

Any research activities that could damage or interfere with this site must be undertaken with support of traditional owners and in compliance with the law.

Changes to the act came into effect in January this year and included significant increases in penalties for those who damage or interfere with Aboriginal heritage without authorisation.