Cultural stand-off risks South Australian rock art turning to rubble

The national heritage-listed Koonalda Cave holds unique Indigenous engravings but their preservation is now threatened.

Ancient rock engravings in the 40,000-year-old Koonalda Cave in South Australia are at serious risk of decay, according to scientists and Indigenous owners, after the state government halted research at the national heritage site.

The ban comes after a two-year consultation process failed to decide which Indigenous group has the right to be the “cultural monitors” of archaeological work at the remote Nullarbor Plain site 900km from Adelaide near the border with Western Australia.

Two groups of traditional owners and native title holders and an Indigenous advisory group have agreed that tests of water, temperature and humidity at the internationally renowned cave should go ahead, but it is understood they cannot agree who should oversee the work by a team led by archaeologist Keryn Walshe.

Dr Walshe, who began researching the limestone cave and its unique “finger fluting” art almost 30 years ago, said on Monday that the failure of the state and federal governments to exercise their powers and choose between the competing groups was a devastating outcome.

“They’ve chosen to find fault within the Indigenous stakeholders rather than take responsibility for protecting a site they are legally responsible for,” she said. “The state departments involved, and their ministers, have failed even the lowest standard of conservation practice.”

Her research at the site had been on hold for more than 2½ years as she awaits the result of the review process, but she has now been told verbally that it cannot resume.

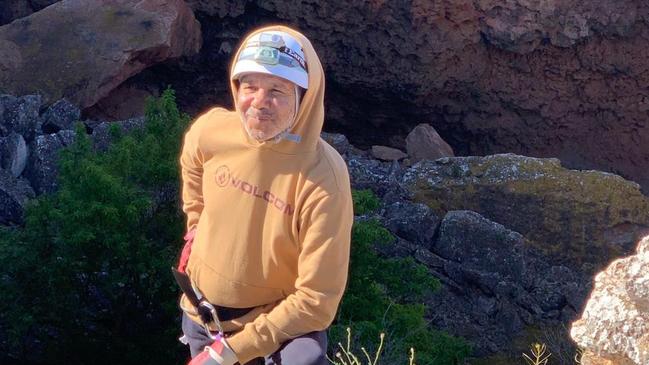

Clem Lawrie, who is a custodian of the cave and a member of the group holding its native title, and who backs the research, said the ban showed the government was more worried about threats of legal action from one of the Indigenous groups than in protecting the cave.

Koonalda sits in the Nullarbor Wilderness Protection Area and is located on the native title land of the Far West Coast Aboriginal Corporation (FWCAC).

Two other groups – the Nullarbor Parks Advisory Committee (NPAC)) and the Council of Mirning Elders (CME) – are officially acknowledged as having a voice in the management of the cave and were involved in the long consultation process.

Mr Lawrie is a member of FWCAC, which previously issued research permits to Dr Walshe. He is also chair of NPAC.

He said the groups had agreed on a conservation management plan predicated on baseline scientific research, but he had been told by the state Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation that the CME had threatened legal action if FWCAC entered the site.

Mr Lawrie said that there had been a complete failure on the government’s part in putting the CME – which had also raised issues of intellectual property and the problem of women entering the site – ahead of the advice and decisions of other stakeholders.

The dispute over who should oversee research has dogged the review process, which began after Mr Lawrie, Dr Walshe, who is a freelance archaeologist; and speleologist Dr Clare Buswell, who is an adjunct lecturer at Flinders University, and chair of the Australian Speleological Federation’s conservation commission, discovered extensive graffiti at the site in July 2022 and raised the alarm.

The site was shut down and the researchers shut out as the South Australian government sought and was granted $400,000 from the Australian Heritage Commission to protect the site. Razor wire was added to a gate at the cave opening, but the state Department for Environment and Water launched a review to develop a conservation management plan for the cave. The Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation was also involved but none of the researchers was allowed input into the two-year process, which also involved a private consultant.

Dr Walshe said that while some of the $400,000 grant would now be used to install surveillance cameras, it appeared most of the money had been spent on the consultation. She understood $85,000 allocated for her research via a Canadian university was now to be returned to the commission.

She said that while vandalism was a major issue for the cave, the biggest long-term threat to the art was changes in climate.

“The cave environment has been stable for at least 40,000 years and that has allowed the rare and extensive engravings to be preserved,” she said.

“But the optimal cave conditions required for preservation are not known. The only way to know is by measuring fluctuating forces – temperature, humidity, air flow and water levels. This type of analysis is long term and it’s critical to the overall understanding of optimal conditions inside the cave that preserve the art. But we have no idea of those optimal conditions.”

She said the Department for Environment and Water had never undertaken baseline measurement in Koonalda Cave even though this was standard practice around the world, and in other parts of Australia. Data loggers to measure baselines had been placed in the cave in 2021, but the department demanded their removal after the vandalism in 2022.

Dr Walshe said DAAR had also intervened by claiming, at the end of the consultative process, that a clearance was needed under a section of the state’s Aboriginal Heritage Act which covered any disturbance or destruction of a site.

“But there is no disturbance or destruction involved in digital recording and placing data loggers on the ground,” she said. “This is a furphy.”

Koonalda’s uniqueness was recognised internationally when it was first explored in 1956 but by the late 1970s, research funds had dried up and it was only in 2006 that Dr Walshe, then working at the Museum of South Australia, resumed work there. In 2014 Koonalda was given national heritage listing and the following year Dr Walshe gained support of the FWCAC to continue the work.

A spokesperson for DEW said the primary aim of the consultation was to protect Koonalda from vandalism.

“This is being achieved through the development of a conservation management plan, improved understanding of the cave and its environment and installation of security equipment,” the spokesperson said.

The final conservation management plan had been endorsed by the Nullarbor Parks Advisory Committee last week and would soon receive final approval from the director of National Parks.

“Following that approval, a new security camera array will be established at the cave to improve the protection of the natural and cultural heritage values of the site,” the spokesperson said. “DEW values scientific research on conservation reserves to improve our knowledge and assist management decisions. Research in the cave has been undertaken via permit and, during the consultation for the conservation management plan, questions were asked regarding aspects of future research proposals. Further work is required to reach an agreement addressing those questions. Once addressed, research will be able to continue at the cave.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout