With the bounty comes an obligation and opportunity to make things right

Our parliament gives us both Lidia Thorpe and Jacinta Nampijinpa Price – the voice will have hits and misses, too.

We are one of the most successful nations on the planet, replete with natural resources, enjoying the benefits of economic prosperity, personal liberty and strong institutions, with a welfare net and a peacefully diverse population. We do ourselves occasional harm that we hope will be transitory (such as undermining our cheap energy advantage for climate gestures and surrendering our freedom and fiscal strength during pandemic paranoia) because there is no reason our good fortune should not continue.

But there is a single enduring blight that we struggle to overcome – reconciliation with our Indigenous population. In practical terms this means closing the substantial gap in life outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, and in political terms it means reaching a settlement over the dispossession and mistreatment of the past in a way that will provide confidence for the future.

Contemporary Australians are not guilty for the misdeeds or misguided indifference of previous generations but, just as we inherit the fruits of their labours, we must deal with the consequences of their unresolved engagements. The bounty handed down to us brings with it an obligation and opportunity to make things right.

We have made progress, from the 1967 referendum to native title rights, and from policy initiatives to improve education, health and law and order outcomes to inquiries and apologies. But we are left, still, with a chasm to be crossed.

In some Aboriginal communities most children are born into despair, which is a situation none of us should tolerate. We are part of an ongoing national project, not passengers on a completed vessel; if our forebears had not accepted this, we would still be a collection of British colonies.

Late 19th-century colonialists understood the notion of Australia and enacted a federation project to enhance and improve it. Most citizens today, whether they were born here or migrated, share that goal of constant improvement.

While the debate about a constitutionally enshrined voice to parliament has become racially divisive and polarised at times, it strikes me that the place to start is with this shared project. There is a broad consensus that reconciling Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia is a worthy and necessary goal, even if the final result might be partly in the eye of the beholder.

If we focus on what John Howard called practical reconciliation the unanimity is even clearer. There is an obvious social and moral value in ensuring that the opportunity for healthy and productive lives should not be drastically lower for Indigenous children compared with the rest of the population. The life expectancy for Indigenous boys born last decade is in the low 70s, 10 years less than for the overall population; for girls, the life expectancy gap is slightly smaller, just under 10 years. The latest figures show that out of every 100,000 Indigenous Australians, 2222 are in prison (an incarceration rate of 2.2 per cent); for the rest of the population there are 164 people in prison per 100,000 (or 0.16 per cent).

Add to this disastrous comparisons in education, employment and domestic violence, and you have hard data that defines our national shame. Contemporary Australians do not have to accept blame for this or to apologise but it is ours to help fix.

This is the cause on which most Australians agree – we all want reconciliation and closing of the gap. There is also broad support for Indigenous recognition in the Constitution because, as Tony Abbott put it, rather than altering our founding document this would “complete” it.

Given the push to enshrine a voice to parliament in the Constitution is driven by these aims of reconciliation and closing the gap, we can see the opposing sides cannot be far apart. If we all aspire to a similar outcome, neither side need demonise the other. In the context of the historical challenge, the differences over the voice are minor. Scott Morrison’s Coalition government was committed to legislating local, regional and national voices, and many opponents of the current constitutional proposal have no objection to a legislated voice.

This means constitutional enshrinement is the only sticking point. It is not much of a hurdle given the proposed constitutional wording has been public for many months and has not drawn any serious criticism. Former chief justice of the High Court Murray Gleeson has declared a constitutionally mandated advisory body “hardly seems revolutionary” and another former chief justice, Robert French, says it is a “sensible and straightforward” proposal that does not constitute a third chamber.

A raft of other constitutional experts have described it as safe and limited – a change that will not lead to judicial overreach or unintended consequences.

Given the widespread acceptance of the desirability of constitutional recognition and some form of representative input from Indigenous Australians into laws and policies directed at them, it is only the fears about constitutional complications or precedent that matters. Unless there is a risk in this area then the only risk of the voice proposal is that it might fail to make much practical difference – you know, like most everything else that has been tried.

On the upside, it could be a significant step forward in recognising Indigenous aspiration, overcoming a constitutional oversight, and giving Aboriginal Australians a say and more ownership over practical measures to improve their lot. It would enshrine a fair go into our Constitution.

Despite fearmongering by some commentators and politicians about “race-based rights” and “apartheid”, there has been precious little follow-through on how the proposed constitutional amendment could lead to judicial activism or racial division. This is not about race anyway, but indigeneity, and it aims only to give Indigenous people the right to have a representative body offer non-binding advice to parliament and government on issues that pertain specifically to Indigenous people.

The hysteria about a racial divide is blown away by the fact even the people running that line also say they have no problem with a legislated voice. How can a legislated voice not be racially divisive while one legislated because of a constitutional requirement would be?

The point about constitutional enshrinement is merely that it will guarantee there must be a voice. A legislated voice might be amended or abandoned, a constitutionally enshrined voice could only be amended – although eventually, of course, it could be dispensed with by referendum.

A broad consensus of Indigenous Australia has made clear this is the only way they want constitutional recognition expressed. This is a repudiation of mere symbolism in favour of an aspiration to deliver constitutional recognition with practical potential.

As someone who has worked across these issues over the past couple of years through my appointment to the Morrison government’s co-design committee, my concerns about it are more prosaic. There is a great risk it will become another layer of bureaucracy between Indigenous problems and solutions, and a risk it will be thrown into a contest of authority and ego between various Aboriginal bodies.

In the co-design deliberations it was made clear the voice would not displace existing organisations. But this cannot hold.

This guarantee to existing organisations might be important to avoid acrimony or opposition from existing Indigenous bodies. But for voices to succeed at a local, regional and national level they must eventually subsume some representative bodies.

The government must not be left wondering whether to listen to the Coalition of Peaks, the National Voice or some other body.

The voice network should subsume other organisations. Rather than suppress these debates until after the referendum, we should have them now so we can see how the architecture of Indigenous organisations can be rationalised and streamlined under a voice, rather than congealed. There should be an efficiency dividend.

Will a voice work? Maybe, maybe not. It is like asking whether parliamentary democracy works – sometimes it does and sometimes it does not, depending on the mix of representatives.

But in principle it is right, and when the right people approach it with the right attitude it is a powerful force for good. Likewise with the voice. It could be brilliant, ensuring governments get grassroots advice on the best way to tackle chronic issues, with the ownership of the Indigenous input inviting a reciprocal obligation of responsibility and accountability.

It will not be seamless. Our parliament gives us both Lidia Thorpe and Jacinta Nampijinpa Price – the voice will have hits and misses, too. But we must ask ourselves whether we are doing so well on reconciliation now that we can afford to reject this modest proposal put forward by Indigenous Australians after broad consultation. Especially when there is no credible downside risk.

There is a passion against the voice from some quarters that is difficult to fathom, even when you consider the radicalism and spite that comes from some of the green-left proponents. This national project should be far too weighty to be knocked off course by the antipathy at the fringes of both sides. Better to cling to the middle ground, ask whether this is worth a go, and consider whether there really is any discernible risk. What we do know is that this proposal is fair and reasonable, and that everything we have tried so far has failed.

While closing the gap is a prime national challenge, there is another side to reconciliation, the non-Indigenous side.

To grasp the historical opportunity of the voice we need to embrace the notion that success would not only be a gift of justice and recognition to Indigenous Australians but a reform to enrich us all and make a better country.

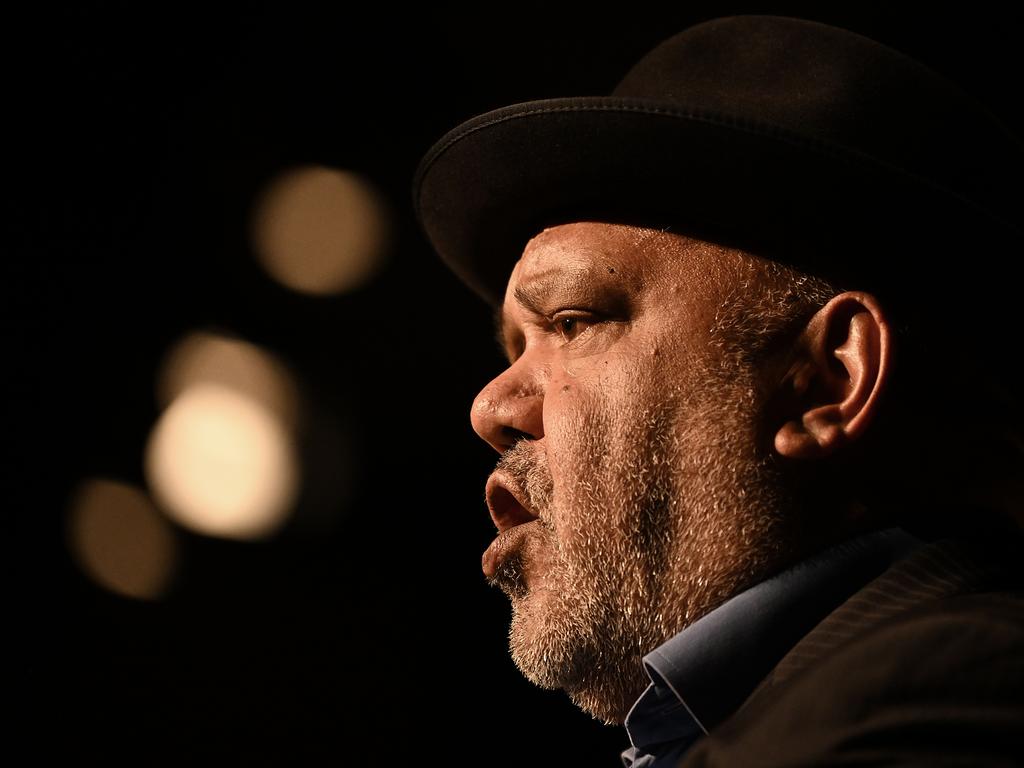

In his first Boyer lecture last week, Noel Pearson spoke of how the insecurity (my word, not his) of non-Indigenous Australians contributes to an unease around these issues.

“It is a troubling and unsettled question, involving denial and defensiveness and how to deal with guilt and truth,” said Pearson.

“It is also such an old question going back to colonial days: if the colonists recognised the Indigenous then, would that not be a repudiation of who they were and their place in this country?”

It is an insightful observation, and it explains why some people are resentful towards Indigenous Australians. Recognition and a voice should bring us together, especially when Indigenous Australians also recognise the advantages delivered by British institutions and multicultural migration.

Filmmaker Rachel Perkins explained the inevitability of this in her first Boyer lecture three years ago when she focused on the obvious shared cause of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians: “It is our love for our country, our land and our sea, that binds us together and makes our futures inseparable.”

That is unarguable, and it suggests we best get on with it.

Chris Kenny will moderate “It’s the voice, do we understand it?” at News Corp’s Beyond ’23 event on Tuesday.