So much emotion evident in every Voice raised in support

Noel Pearson’s stirring call last week for Australians to adopt the Voice illustrates why it should fail.

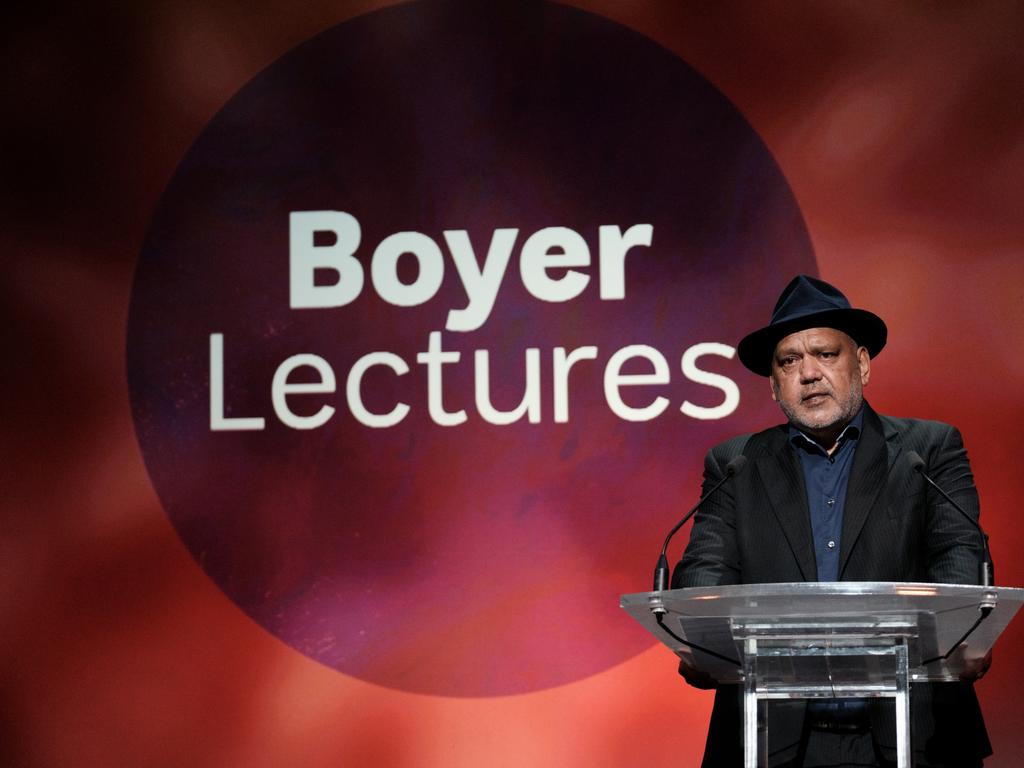

Pearson’s lecture is a magnificent piece of oratory. Its assertions, at least while unexamined, appear unchallengeable. Pearson’s truth is, at least to him, self-evident. He says “let me point out what is incontrovertible: Australia doesn’t make sense without recognition. Until the First Peoples are afforded our rightful place, we are a nation missing its most vital heart.” Then comes the rhetorical sleight of hand – recognition means a constitutionally entrenched Voice. The rightful place of Indigenous Australians is a special body open only to them, with rights not afforded to other Australians. Moreover, Pearson promises, if Australians vote “yes” to the Voice, “racism will diminish in this country”.

This encapsulates the strengths and weaknesses of the case for the Voice. It is highly emotional, highly dependent on assertion and feeling. It claims to appeal to our better angels. But this is also when its halo starts to slip.

Appeals to emotion easily slide into emotional blackmail. The implication is that failure to adopt the Voice is racist, or at best lacking in moral sensibility and empathy. Those who don’t want a new untested and unknowable institutional structure inserted into our highly effective Constitution are not merely wrong but bad.

From there, of course, it is easy to justify stern measures against opponents of the Voice. The cancellations have started in earnest with Facebook’s recent action to de-platform a video opposing the Voice by two Coalition senators, Jacinta Price and James McGrath. Prominent lawyers refuse to go public with their significant concerns about the legal consequences of the amendment to the Constitution proposed by the Prime Minister because they know it will put their professional careers and prospects at risk. The government is testing ideas to ensure the “no” case receives no public funding and its proxies are examining ways to amend the law governing constitutional referendums to ensure the Voice gets up. The government seems committed to forcing the Voice on us by hook or by crook. There is more than a faint hint of thuggery in all this.

This is, of course, all hugely counter-productive. A Voice forced on us by emotional blackmail and without careful, dispassionate logical analysis will not heal racism. It will exacerbate it.

It was always dubious to assert that we could reduce racism by giving one race preferential constitutional privileges over all others. But to crowbar the Voice into the Constitution by saying, to quote Greg Craven, that “Indigenous souls would be broken” if we don’t agree to the Voice is a recipe for future anger and division.

While Pearson is entitled to his rhetorical flourishes, and indeed one would expect to find them in the Boyer lectures, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians would benefit enormously from removing the emotion from this debate and doing some cold hard analysis.

For, with respect to Pearson, many of his propositions are far from incontrovertible, and asserting them does not make them so. For example, even if one accepts that some form of constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians is appropriate, the Voice is possibly the most overreaching and contestable method of recognition one could imagine.

Recognition of Indigenous peoples certainly is not synonymous with conferring constitutional privileges on them not shared by non-Indigenous Australians. Recognition need not mean an end to equal treatment under the Constitution. One could revisit the proposed preamble, adopt a legislated Voice able to be abolished by parliament if it becomes unnecessary or ineffective, or adopt any of the moderate suggestions for constitutional amendment that until recently were the preferred options even of activists.

Until recently, a range of mechanisms for recognition of Indigenous Australians focused on modest and defensible constitutional amendments to abolish section 25 of the Constitution (which authorises disfranchisement of certain racial groups in some circumstances) or amendment or abolition of section 51 (xxvi) of the Constitution (the so called “race power”).

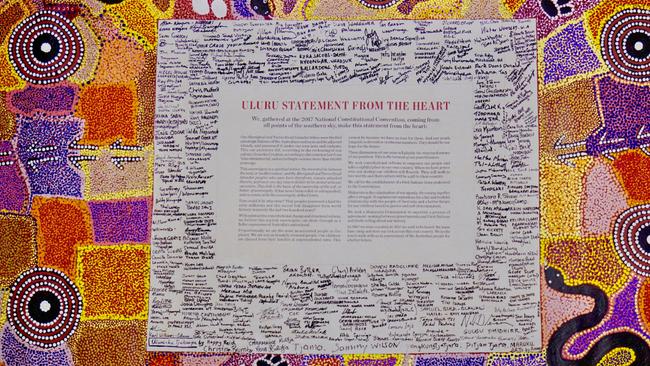

It was only when the Uluru Statement was adopted in 2017 that the much more radical option of a Voice became the preferred instrument of activists. Indeed, the Uluru Statement as a whole, with its highly contestable claims of co-sovereignty with the Crown, needs a lot more careful analysis than it has received, but that must await another day.

For now, we do need to scrutinise rigorously both the fundamental premise of a Voice and its practical implications as outlined by the proposed Albanese Amendment to our Constitution.

The fundamental premise that we should divide our population up into Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians with different rights and privileges dependent on their race only needs to be stated to understand why many Australians, probably most, may object to it. But even if you accepted the fundamental premise, there are at least two major problems with it which have not been addressed, properly or at all, by the government or by Voice activists. There are numerous other problems but these two will do for today.

The first is parliamentary supremacy. The Albanese Amendment makes the High Court the final arbiter of the powers, privileges and processes of the Voice, not parliament. As the amendment stands, no legislation passed by parliament can change the fact that if the High Court does not think that legislation accords with the purpose and function of the voice as expressed in the amendment or implied by the High Court from the express words of the amendment, the High Court’s view, not parliament’s, prevails. This confers on the Voice, its members and any other activist, enormous powers to hold parliament and the executive government to ransom by exploiting the resulting opportunities for litigation and lawfare.

The Voice would in effect become a piece of constitutional ransomware able to be activated almost at will, and with the opportunity for enormous pay-offs. Voice activists pooh pooh this analysis, saying it can’t happen and that the Voice is not justiciable, in other words, beyond the reach of the courts. But the best evidence that leverage and lawfare is precisely the purpose and effect of the Voice is that when pressed to insert some self-destruct language in the Albanese amendment to dissolve the Voice if it ever becomes justiciable, activists angrily reject any such safeguard.

The second big issue for today is the Voice’s remit. The language of the amendment makes clear the Voice will give Indigenous people an extra say not only on matters affecting Indigenous people only but also matters affecting non-Indigenous people (provided some relevant nexus with Indigenous affairs is found).

Again, one could clarify this by inserting into the amendment a provision saying the Voice has no jurisdiction over matters which can affect non-Indigenous Australians, and again, activists angrily reject any such attempt to curtail the Voice’s extraordinary reach.

These, and a host of other issues, need careful, considered thought. So, while one may admire Pearson’s gifts with the English language, can we please skip the emotion and the rhetoric in favour of some hard-headed logic.

Chris Kenny will moderate “It’s the voice, do we understand it?” at News Corp’s Beyond ’23 event on Tuesday.

Noel Pearson’s stirring call last week in his first Boyer lecture for Australians to adopt the Voice in our Constitution illustrates not only why there is much emotional support for the Voice, but also why the call for the Voice should fail.