William Deane’s letters show how Queen avoided the republic limelight

William Deane’s vice-regal letters reveal the Queen avoided coming to Australia in the lead-up to the 1998 constitutional convention and 1999 republic referendum.

William Deane’s vice-regal letters reveal the Queen avoided coming to Australia in the lead-up to the 1998 constitutional convention and 1999 republic referendum but was advised her long absence from Australia could encourage the view that “the Queen doesn’t seem to come to Australia anymore”.

Buckingham Palace, though mindful the Queen had not visited since 1992 and would not visit again until 2000, was determined to ensure she was not seen as “campaigning” for the monarchy in this period of growing support for a republic.

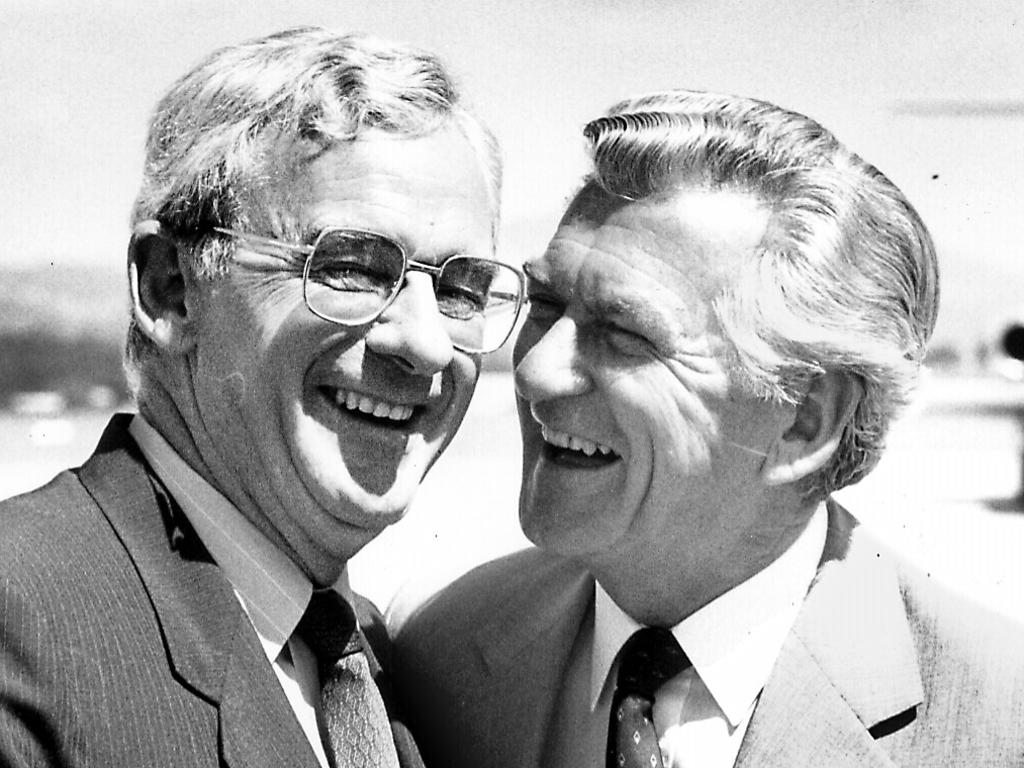

The then-governor-general and prime minister John Howard were eager for the Queen to visit Australia. They made a formal request for a royal tour in 1998 and assured her of a warm welcome. But the invitation was declined.

“Her Majesty is, however, personally held in such high regard in this country that I don’t think there would be any real danger of a visit being disrupted or marred by significant hostile demonstration on the part of those who support a republic,” Sir William wrote to Sir Robert Fellowes, the Queen’s then-private secretary, in March 1997.

Sir Robert repeatedly said the Queen was eager to avoid “contention and controversy” ahead of the republic referendum and especially any suggestion “that she was in some way campaigning for the retention of the monarch in Australia,” he wrote in October 1998.

Sir William’s secret correspondence with Buckingham Palace is now open for access at the National Archives of Australia. Appointed on the advice of Paul Keating, and holding office from February 1996 to June 2001, Sir William signed off his letters: “I have the honour to remain, Madam, your majesty’s dutiful servant.”

The convention and referendum feature prominently in Sir William’s correspondence. Buckingham Palace worked with Mr Howard’s office to prepare statements for the Queen to be issued in the event the referendum was carried, defeated or there was a majority vote but not in a majority of states.

While the governor-general provided updates on the public mood ahead of the referendum, he thought the odds of it being carried were slim. Buckingham Palace maintained a consistent position on the republic: “The Queen regards this matter as one for Australians to decide,” Sir Robert wrote in February 1998.

When Sir David Smith, the former official secretary at Government House, argued the governor-general was actually head of state, Buckingham Palace made it clear in January 1999 that this argument, often propagated by monarchists, was nonsense and the Queen was indeed Australia’s head of state.

Sir William gave voice to his strong views about addressing injustices faced by Aboriginal Australians and his support for reconciliation. He did not criticise Mr Howard for not apologising to the stolen generations. “Although it is of course the case that reconciliation would be on a different path if the prime minister had different views relating to it, commentators can exaggerate the issues,” he wrote in March 2000.

The governor-general did, however, tell the Queen that Pauline Hanson’s “intolerant and ignorant” views on racial matters had done “considerable damage” to Australia in the eyes of the world in August 1997. Sir William further described her statements as “extremist” and appealing to “ignorance, intolerance and racial prejudice” in June 1998.

The controversy over Mr Howard’s preference to open the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games, which he ceded to Sir William, is also discussed in the letters. The governor-general asked Buckingham Palace for advice. Sir Robert wrote that he could not see any argument for why the prime minister should open the Games. In October 2000, Sir William wrote that he did not enjoy opening the Games anyhow.

Several policy and political matters are canvassed in the correspondence. Sir William informed the Queen about the scandal enveloping Bronwyn Bishop over the “poor treatment” of aged care residents, the introduction of the GST and the sale of Telstra. He reported that Mr Howard and Labor leader Kim Beazley were “both decent and genuinely committed men”.

He conveyed his concern over economic and social divisions between urban and regional Australia. “The economic divide is reflected to some extent in differences in social and political attitudes, not so much traditional left and right, but rather in a sense of increasing alienation in the country and a mistrust of politicians and the democratic process,” he wrote in March 2000.

The National Archives has released more than 3000 pages of vice-regal correspondence between governors-general and Buckingham Palace between 1965 and 2001. Contrary to the claims of certain academics, the seven governors-general write candidly about politics, express concerns about policy, assess government and opposition figures, and some ruminate on their reserve powers.

Sir Robert told Sir William in March 1997 that Buckingham Palace had “indefinite powers” to keep the letters from “public gaze”, but they have since been classified as Commonwealth records and open after 20 years.

As with other correspondence, the National Archives has made extensive redactions to Sir William’s dispatches which run counter to the spirit of Australians having a right to know their history. These redactions are often about mundane matters such as the scheduling details of a royal visit to Australia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout