As the ABS reported on Thursday, there are now over one million more people working than before the pandemic.

The overblown monetary and fiscal responses to the crisis are coming home to roost in higher inflation and debt, and the consequent “normalisation”, as officials describe it, of interest rates and the budget.

But there is, nevertheless, a platinum lining for Australia: a 3.5 per cent unemployment rate, record levels of employment and bountiful participation.

Look at our peers in the rich world and even amid a cost-of-living squeeze we’re doing really well on the economists’ old “misery index” of unemployment plus inflation.

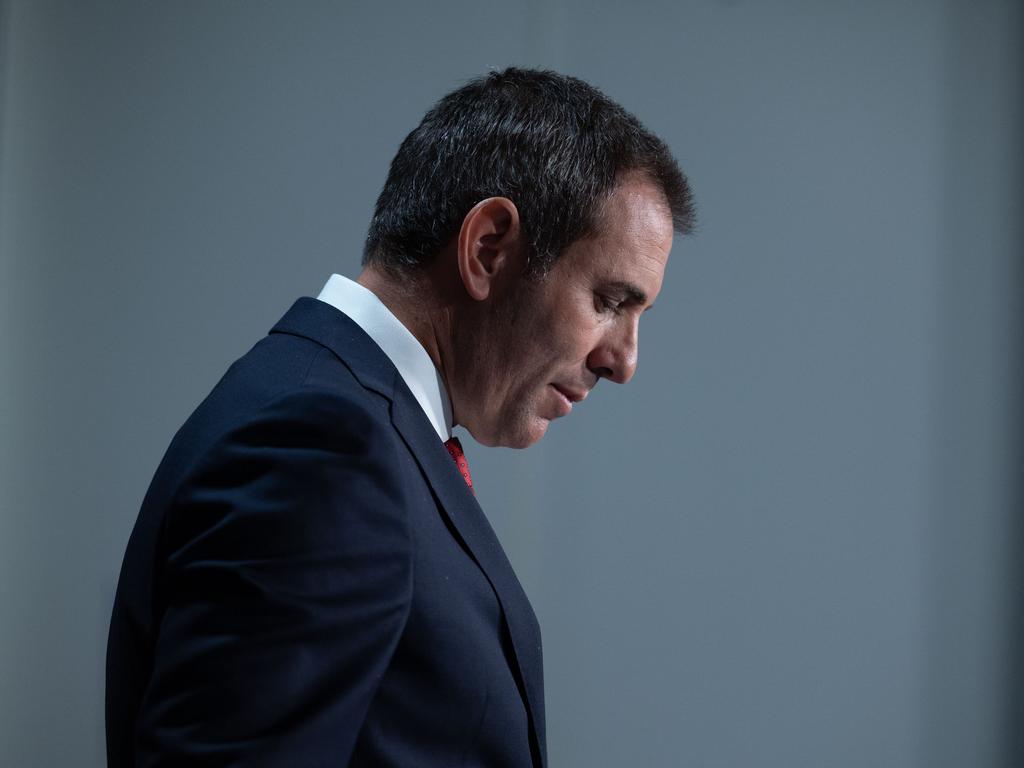

Treasurer Jim Chalmers is releasing the first iteration of the Measuring What Matters statement on Friday.

It’s sold as trying to track the nation’s progress, but it’s hard to see it as anything more than a pitch to progressives living in Green and teal colonies.

Boil down the Treasurer’s “values capitalism” vibe and it’s another piece of political marketing and of a piece with the fads in New Zealand and Mathias Cormann’s OECD bolthole in Paris.

You wonder what the point is of bringing under a wellbeing tent 50 indicators and five broad themes that governments are already profoundly attuned to.

Then consider the things that are truly fundamental and only get cursory treatment. Poverty is mentioned only once in the document circulated by Chalmers.

Or freedom. Perhaps that is so elemental we take it for granted like the air we breathe (although air quality, “stable or little change”, does make the fabulous 50).

Chalmers insists we already have big-picture measures such as Gross Domestic Product, income and employment, and while he says they are important, “they don’t capture the full story”.

One senior Canberra identity speculates that putting together an itemised list motivates all those agencies involved to pursue better outcomes in areas that have deteriorated, such as homelessness, and don’t get much attention outside of CEO sleep-outs.

Maybe, but productivity looks a bit forlorn and forever neglected at the bottom of the naughty list; getting more out of our precious capital and labour should be a national mission.

There are various ways of looking at human development and how nations are tracking. As one senior government economist put it, income per person is pretty hard to go past.

To debase a Nobel laureate, money isn’t everything, but in the short-run it’s almost everything when it comes to how well a country is doing, America aside.

That’s why full employment, which the Albanese government has elevated and will be at the centre of the Reserve Bank’s new mandate, is the alpha and omega.

As Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy said in April, the health and wellbeing benefits of being employed are often overlooked.

Long-range data from the invaluable Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey show working is associated with better mental health and lower rates of psychological distress.

“We also know that there are strong intergenerational benefits as children with parents who work are more likely to work themselves,” Kennedy told a conference on full employment.

There’s a debate about what the level of full employment is. Let’s be bold.

We shouldn’t settle for the likely 4.5 per cent that Michele Bullock nominated last month that will coincide with the return in mid-2025 of consumer inflation to the top of the 2 to 3 per cent target band.

Pushed on by trade unions and a host of others, will Chalmers sign up the new RBA governor to an employment goal more in tune with today’s near 50-year jobless low? Or lower?

A hard, skinny number to aim for is good for accountability and messaging.

University of Melbourne economist Jeff Borland says it‘s universally accepted that it’s infeasible we’ll eradicate unemployment and underemployment; the jobs market is in constant flux.

Pushing job growth too hard causes other problems, such as wage inflation, which inflicts other ailments.

“Working to achieve a specific target for full employment means policy is directed towards improving wellbeing,” he writes in Inside Story this month.

In this balancing act, Borland reckons keeping the current 3.5 per cent jobless rate would “generate substantial benefits for national output and equity”, compared with returning to the 5.5 per cent we averaged through the 2010s.

Perhaps an even better approach, Borland argues, is chasing a broader indicator, combining unemployment and underemployment, known as “labour under-utilisation”.

To my mind, that translates to “no one is held back and no one is left behind”. Sound familiar?

That’s a form of wellbeing that is actually authentic and is worth us all aspiring to.

The best form of wellbeing is a job.