Spy agencies face biggest overhaul in 40 years

ASIO will be given greater flexibility to spy on Australians, including dual citizens living here, to help disrupt foreign interference.

ASIO will be given greater flexibility to spy on Australians, including dual citizens living here, to help disrupt foreign interference campaigns in a move aimed at closing a “gap” in the nation’s security and intelligence framework.

The proposal is part of the biggest intelligence architecture shake-up in more than 40 years, aimed at strengthening Australia’s national security laws and improving offshore operations while equipping spies with “fit-for-purpose” powers and breaking down barriers between agencies.

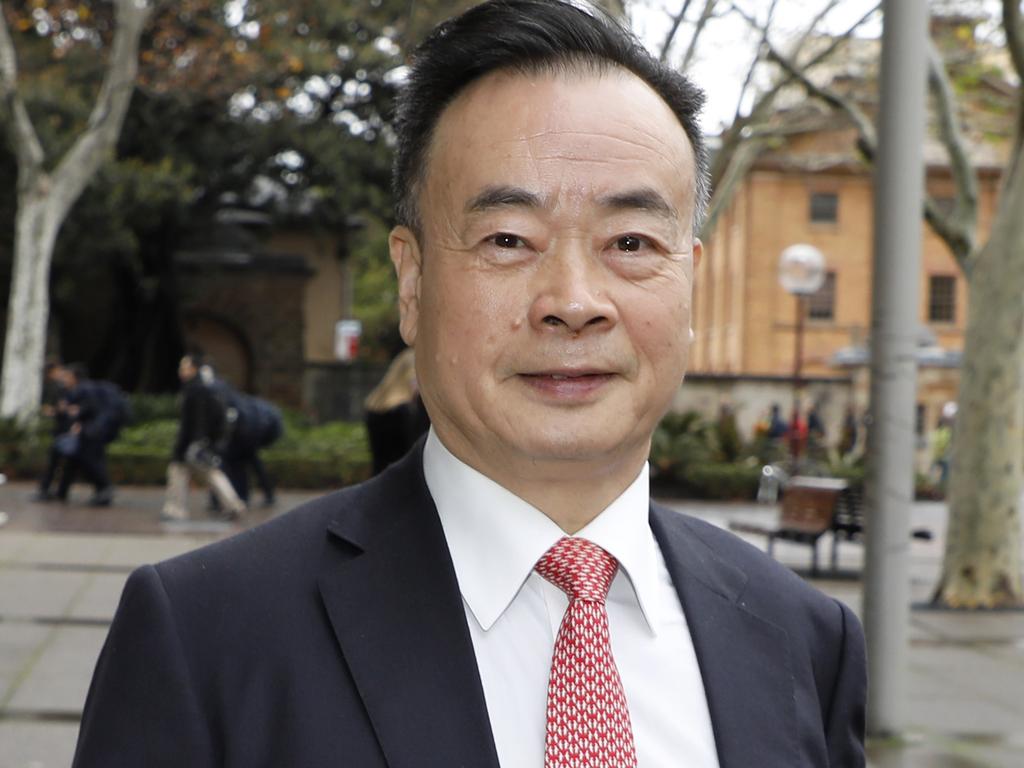

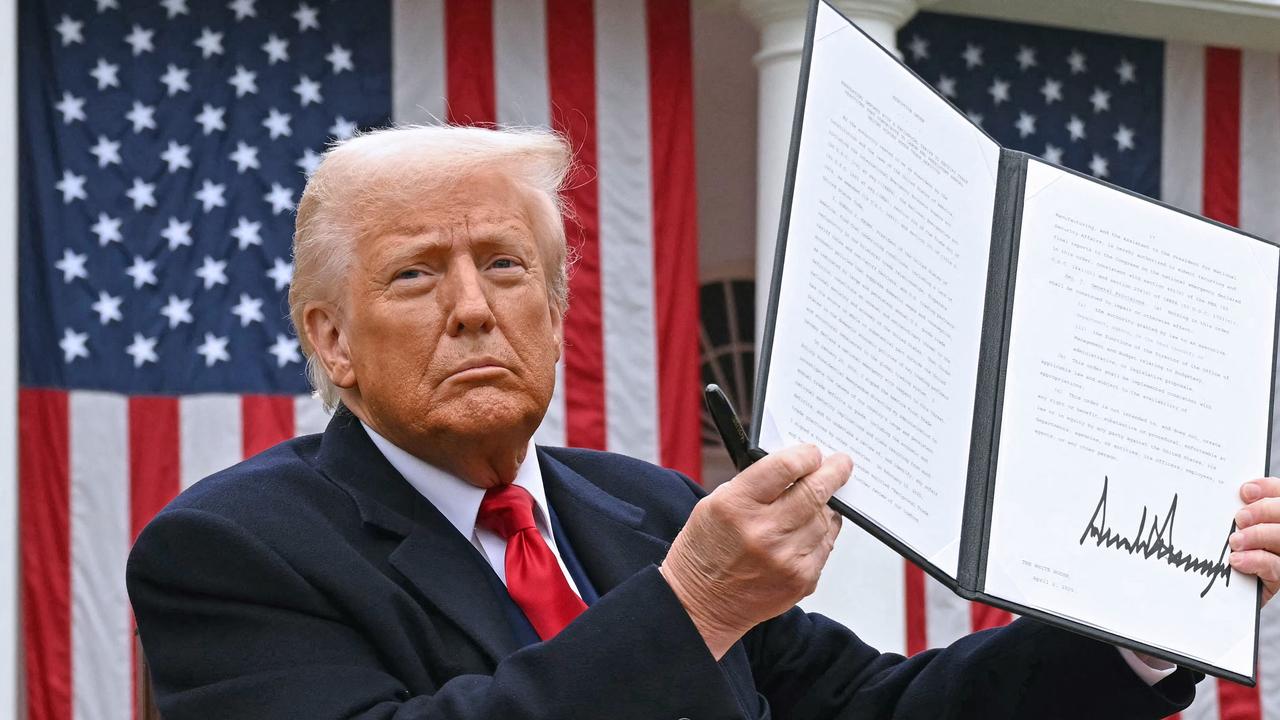

Attorney-General Christian Porter on Friday confirmed the government would adopt all but four of the 190 recommendations outlined in the $18m national intelligence review led by former spy chief Dennis Richardson. An additional 13 classified recommendations have been endorsed.

Amid increasing foreign interference threats, Mr Porter said the 1600-page review had identified a gap in ASIO’s legislative framework that required tightening and cited the example of an Australian citizen holding dual citizenship who had previously worked overseas for a foreign government.

“They return to Australia and are undertaking very similar activities, but ... there are restrictions around the way in which you could get the same information that you are trying to get offshore, onshore,” he said. “So that type of circumstance you can imagine is arising with greater frequency ... We’ve obviously agreed with that recommendation, but it is a problem.”

Mr Porter also said the government would develop an Electronic Surveillance Act to replace “unnecessarily complex” legislation, which had been “outpaced by technology” including smartphones and end-to-end encryption.

All security agencies operating overseas — apart from the Australian Secret Intelligence Service — would also have to “consult and inform” the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade when engaging in “covert human intelligence zactivity offshore without the knowledge of the host authorities”. The government will also apply greater rigour to overseas intelligence activities that could harm Australia’s foreign relations and other offshore security operations “if revealed or compromised”.

In the review, Mr Richardson — a former head of the Defence Department, DFAT and ASIO — criticised some security agencies for suggesting existing laws were “ad hoc, piecemeal and inconsistent”.

“On closer examination, it was often apparent that these barriers, to the extent they in fact were barriers, were not due to legislation, but rather to culture, policy or practice,” he said. “In other cases, a perception of the existence of barriers stemmed from an immature understanding of the foundational principles governing the intelligence agencies.”

Australia’s former ambassador to the US said this lack of understanding led “some agencies to suggest that legitimate safeguards should be removed to … facilitate better information sharing or relieve administrative burdens”.

“One member of the NIC (national intelligence community) saw ‘legal requirements’ as a hindrance to data and information sharing. The ends do not always justify the means and the referenced legal requirements are important features designed, amongst other things, to protect individuals’ rights,” he said.

Mr Richardson also raised “cultural barriers” between intelligence bodies over recognition of security clearances.

“Agencies do not always trust the quality of each other’s vetting processes. This means clearances cannot always be seamlessly transferred between agencies, and mobility of staff can be impeded. It is simply not acceptable that Australian agencies accept the clearance, without question, of their Five Eyes counterparts, but not always those conducted by their fellow Australian agencies.”

Mr Richardson, who handed over his 18-month review to government last December, recommended legislative amendments enabling the ASIO director-general of security, on request by the foreign or defence ministers, to seek a warrant from the attorney-general for the “collection of foreign intelligence on an Australian person who is acting for, or on behalf of, a foreign power”.

Mr Porter said while the report had found the “key principles that underpin Australia’s intelligence legislation are sound”, issues had been raised in relation to how warrants were issued and the need to overhaul existing electronic surveillance powers, described by Mr Richardson as a “dog’s breakfast”.

In his report, Mr Richardson said “much has changed over the past 30 to 40 years”, citing rapid shifts in intelligence capacity and priorities following the September 11 terror attacks and the new threat of cyber attacks.

Amid geopolitical tensions across the globe, including the rise of China and refusal by countries including Russia, Syria and North Korea to “act in accordance with international law and norms”, the review warned of “strategic implications for Australia”.

Mr Richardson said between September 2001 and August 2019 parliament passed more than 124 acts in support of national security agencies, including more than 14,500 minor and technical amendments.

“Complex laws also undermine public trust and confidence. It should be clear to the Australian public what intrusive powers are available to NIC agencies, the circumstances in which they may be used, and the limits, controls, safeguards and accountability mechanisms that apply.

“In other areas, it is necessary for the legislative framework to be complex, given it is designed to strike a balance between individual rights and collective security.”

In its response to the review, the Attorney-General’s Department said national intelligence agencies would now advise DFAT before conducting covert “human intelligence activities in another country”.

“Relevant agencies will work together and with DFAT to develop a flexible, nuanced process to assist DFAT in managing any foreign-relations risk,” the AGD said. “To the extent ASIO’s unilateral activities include covert human intelligence collection in a foreign state without that state’s consent, ASIO should notify DFAT of those activities.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout