Second bone-stealing scandal fuels Crowther statue debate, ahead of heritage ruling

More body-snatching allegations surrounding a former Tasmanian premier and his family have surfaced just days before the state’s heritage council decides the fate of his statue.

More body-snatching allegations surrounding a former Tasmanian premier and his family have surfaced just days before the state’s heritage council decides the fate of his statue.

The Tasmanian Heritage Council will on August 18 rule on plans by the Hobart City Council to tear down the Franklin Square statue of surgeon and premier William Crowther.

Its main justification for the statue’s removal – which would be the first of its kind in Australia – is the accusation that Dr Crowther stole the skull from an Aboriginal corpse in 1869.

Dr Crowther denied the charge, which was never proved. In 1878, he was reinstated to his position at Hobart’s general hospital and became premier in December that year.

Now archival material freshly uncovered by amateur historian Scott Seymour reveals that in the same year, 1878, another bone-snatching scandal enveloped the hospital and Dr Crowther’s son and fellow surgeon, Edward Lodewyk Crowther.

A former hospital worker, Thomas Stopford, told police he removed from the hospital’s “deadhouse” two casks “containing the skeletons (pickled) of two men”.

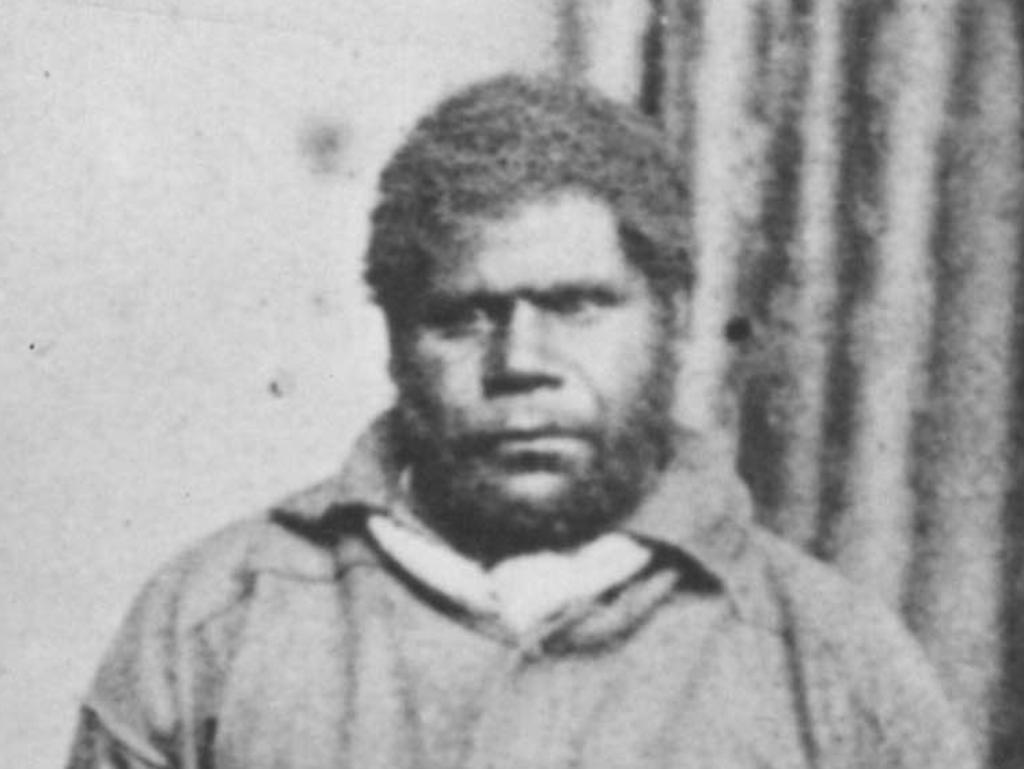

Stopford told police the skeletons were those of pauper William Pinford and South Sea islander Henry Tanna, and that he took them “to the house of Dr EL Crowther in Macquarie Street”.

“I believe the casks and their contents are now buried in the ash-pit at the bottom of Dr EL Crowther’s garden,” Stopford said.

In response, the government ordered the exhumation of several graves, while the hospital commissioned an inquiry.

The inquiry concluded Stopford’s claim about Pinford’s bones was “entirely without foundation”, but “fully sustained” his allegation about Tanna’s skeleton being removed in a tub.

Tanna’s coffin was found to contain “neither body nor bones”, only “sawdust and several pieces of apparently human flesh of very dark colour”.

A house surgeon confirmed the tub with Tanna’s skeleton was removed on Edward Crowther’s orders to “premises conjointly occupied” by Crowther and a medical student, Mr Rawson.

Mr Rawson confirmed Tanna’s flesh was removed from his skeleton, but told the inquiry he had no knowledge of the bones being removed from the hospital.

He suggested any removal was temporary, advising Tanna’s skeleton was currently being used at the hospital for study purposes.

Edward Crowther argued it was standard that “when a body has no friends” it was “handed over to the (medical) students”, licensed by law to study it.

The inquiry suggested any offence by Edward Crowther should be viewed in context: “If the appropriation, for a time, of the bones of an unclaimed deceased fellow creature, for the promotion of an important branch of public education, be a misdemeanour in the eye of the law, or an offence against public decency, then undoubtedly such an offence has been committed.”

Mr Seymour said while the case might cast further suspicion on the Crowthers, the council had acted on erroneous information in deciding to tear down the statue and should pause the process pending the outcome of further research.

Some city councillors and Aboriginal activists, however, argue enough is known about William Crowther’s bone-hunting to justify the bronze’s exile.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout