New clues in search for Tasmania’s King Billy

Fresh evidence emerges in one of the most gruesome, shameful and enduring mysteries of Australian history.

New evidence has emerged to rekindle one of the most gruesome, shameful and enduring mysteries of Australian history: what happened to the stolen remains of Tasmania’s so-called “last man”, William Lanne.

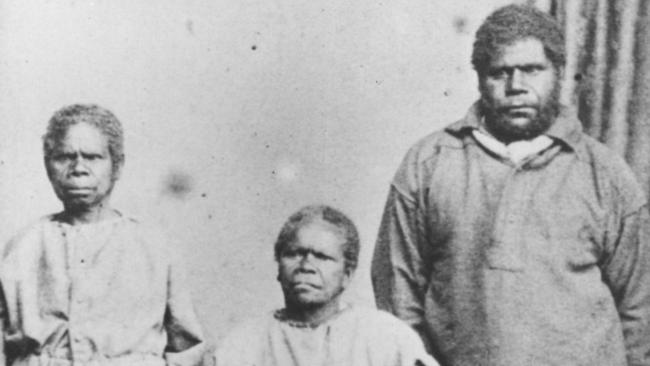

Lanne, or King Billy as he was also known, was a “good natured, jolly fellow”; a hard-living whaler, popular with women at the Oyster Cove Aboriginal settlement south of Hobart. He was, in the flawed language of his time, the last “full blood” Tasmanian Aboriginal man, and married Truganini, who was similarly, and inaccurately, described as the last of their race.

Local newspapers referred to Lanne, or Lanney, as “Tasmania’s last man”. As such, his death from illness on March 3, 1869, made his skeletal remains hot property among Hobart’s rival “gentlemen” bone-hunters.

Eager to win kudos with a scientific community that believed skulls could help “rank” the races, several high-profile society figures began a fierce brawl over who would obtain Lanne’s remains.

Two key protagonists were doctors at Hobart Town General Hospital. William Crowther, later to become premier, wanted Lanne’s remains for the Royal College of Surgeons, London. Hospital house surgeon George Stokell wanted them for the Royal Society of Tasmania. When it appeared the society would prevail, story has it that the wily Crowther invited Stokell for tea at his house on the evening of March 4.

While Crowther’s wife kept Stokell talking, Crowther and his son Bingham were in the hospital’s “dead house”, removing Lanne’s skull and replacing it with that of a white man, whose body was on hand. In response, Stokell and other Royal Society allies severed Lanne’s hands and feet. After Lanne’s funeral and burial, Stokell and his allies exhumed and stole the rest of the body, de-boning it and drying the bones on the hospital roof.

A scandal ensued. Crowther lost his hospital position and Stokell was not reappointed as house surgeon. An Anatomy Act was passed by the Tasmanian parliament to avoid any more unseemly horrors. Lessons were only party learned. True, the Royal Society was prevented from mutilating Truganini’s remains when she died in 1876, but it did win approval to exhume her body, which it later publicly displayed.

No confirmed remains of Lanne have ever been located.

In 1991, a skull thought to have been Lanne’s was returned to the Aboriginal community from Edinburgh University, and given a ceremonial burial. But a scientific report by the university later concluded it was not Lanne’s after all.

In recent weeks, however, a letter found in Tasmania’s state archives by local amateur historian Scott Seymour has shed further light on what happened to Lanne’s remains.

The letter was sent on August 8, 1873, from Morton Allport, a Royal Society member involved in the mutilation scandal, to doctor Barnard Davis, a keen London bone collector and craniologist. The letter shows the Royal Society still had the bulk of Lanne’s remains four years after his death, and suggests the skull was with Crowther’s medical student son, Bingham, at Guy’s Hospital, London.

Boasting to Davis about the society’s Indigenous remains, Allport writes: “A third specimen consists of the greater part of the skeleton of the (so-called) last male Aborigine ‘William Lanney’.

“Of this specimen the head and two vertebrae were stolen from the general hospital Hobart Town by one of the medical officers, and the skull is now believed to be in the possession of one of the students at Guy’s (a Mr Bingham Crowther).”

Allport suggests Davis seek out the skull, but without revealing who tipped him off. “You might very possibly see it (the skull) if you carefully conceal the fact that you obtained this information from me,” Allport writes.

Seymour says the revelations are significant. “The general consensus seems to have been that after 1869 the skull has disappeared and the rest of his remains vanished … perhaps overseas,” he says. “So it’s interesting to read in that letter that some four years after Lanne’s death, the Royal Society still has ‘the greater part’ of the skeleton. It’s obvious they weren’t in a hurry to send those remains overseas.”

The letter also tends to debunk old theories, including that Lanne’s remains were buried at what is now Hobart’s Campbell Street Primary School. Certainly, Allport’s letter suggests there were no skeletal remains there.

If Allport is correct about Crowther’s son having the skull, this would also demolish a story – repeated in several history books – that while being smuggled to England the skull was thrown overboard by sailors outraged at the stench. The letter also raises new questions. If the Royal Society held on to Lanne’s remains in Hobart, where are they now and could they still be gathering dust in a forgotten store room?

Royal Society president Mary Koolhof says all of its collection, aside from art works, were transferred to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in 1885. “The Royal Society has no ancestral remains in its possession,” she says.

TMAG director Janet Carding, however, insists Lanney’s remains were not among those it received. “(TMAG) has no records to indicate that the remains of William Lanne were part of the Royal Society of Tasmania collections which formed the museum,” she says. “Provenance research over a number of years … has not confirmed that Lanne’s remains have ever been a part of the TMAG collection.”

Unless TMAG records are lacking, the Royal Society must have disposed of Lanne’s remains between 1873 and 1885. It seems likely the society – which like TMAG has apologised for its past theft of and trade in Aboriginal body parts – will face further questions and scrutiny of its records.

As to the skull, its fate may never be known. There has been speculation William Crowther sent it to the Royal College of Surgeons in London, which in 1874 made him an honorary fellow.

However, according to a comprehensive 1997 paper by historian Stefan Petrow, the college’s skull and bone collection was destroyed by Nazi bombs in World War Two. A later study of college records found no evidence of a Crowther donation.

The skull returned by Edinburgh University in 1991 had been donated on Crowther’s death by another of his sons, EM Crowther, who believed it to be Lanne’s. However, a forensic facial reconstruction in the early 1990s concluded it was not.

So is it time to let Lanne rest, as best he can, wherever his remains may be? Or should this new information, combined with a renewed focus on Lanne and Crowther, as part of a “truth telling” under way in Hobart, prompt fresh efforts to solve the puzzle?

A new book on Aboriginal resistance fighter Tongerlongeter, by Henry Reynolds and Michael Clements, is also sharpening interest in the Black Wars that preceded the hardships of survivors such as Lanne and Truganini.

Aboriginal leader Michael Mansell has spent decades seeking the return of remains, and was part of the delegation that retrieved the Edinburgh skull and other Indigenous bones in 1991. He wants government funding for researchers to explore more of the vast material in archives, to try to bring home not only Lanney’s remains but those of many other Aborigines who suffered a similar fate.

“Talking about truth telling and a treaty, this is exactly the sort of thing that can be done, so why wait?” Mansell says. “There is so much material in archives. There is a paper trail but it’s hidden.”

Historians, too, still want answers. “If William Lanne’s remains are still out there somewhere, I think it’s important to try to find them if we can,” argues Seymour. “We should at least make an effort to follow the trail until it comes to a conclusion. He deserves that. The Aboriginal community deserves that.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout