Indigenous ‘patriots’ deserve place in our history of heroes

Indigenous warrior Tongerlongeter led a sophisticated resistance campaign against the British in Tasmania.

Australia’s ignorance of and lack of interest in our First Nations’ warriors is a national peculiarity that must surely astound interested foreign observers.

By whatever measure is employed, the frontier wars loom large in our history. They lasted in one form or another for well over a hundred years. They were experienced on the coastlines of the Indian and Pacific oceans, from the southernmost part of Tasmania to the islands of Torres Strait. The death toll will never be known with any certainty, but it increasingly seems likely to have been higher than that of either of the world wars, particularly when we consider that Australia counts among its fallen heroes those who died of any cause, including accidents and disease.

The issues in contention in frontier fighting were by any measure of equal gravity to Australia’s many overseas entanglements.

Frontiersmen and Indigenous warriors were contending for the ownership and control of land across a vast continent. It was warfare on this country for this country. The linked series of local wars was a conflict of global significance. It was, arguably, Australia’s greatest war.

But when Australians seek war heroes, they invariably look to the men and women who battled, suffered and died overseas. The young men who fought at Gallipoli in 1915 are chosen for special attention as exemplars of admirable national characteristics. It is commonly asserted that the nation was made on those distant shores.

Thousands of Australians go there on pilgrimages. As in so many other ventures, it was recognition overseas that mattered. With embarrassed eyes averted from brutal bush fighting, Australia was unable to notice the heroes of the Indigenous resistance. By any fair measure, they stood taller than our servicemen and women who suffered and died overseas. Australian forces were in many cases better equipped, educated and trained than their assorted enemies. They had access to superior medical services and consequently had a much higher chance of surviving injury. They also had what cannot unfairly be called the luxury of fighting on other peoples’ lands. They certainly suffered grievously. But they knew all the while that their own country was safe, that their homes and families were secure, that their own property was sacrosanct, and their way of life inviolate.

None of these certainties was available to the warriors of the First Nations who struggled desperately to hold back the irresistible tide of British colonial expansion. The longer the fighting went on, the more the balance of power tilted in favour of the invader. Vast open plains did not provide the sanctuary of Tasmania’s rugged hinterland. European guns improved out of sight during the course of the 19th century.

Colonial frontiersmen took to the saddle and stayed there. Irregular cavalry, aided by Aboriginal and mixed-descent trackers, was far more effective than the stumbling infantry of early Tasmania and NSW.

Aboriginal warriors faced impossible odds, not just now and then, but always. And yet they went on fighting. In the case of the Oyster Bay – Big River nation, they resisted until there were only 26 of them left. It is a heroic story in anyone’s language. Tongerlongeter and his people were great patriots fighting as patriots have done over time all across the world to defend their homeland against foreign invaders.

Sympathetic contemporaries recognised patriotism when they saw it.

Lieutenant William Darling, when talking to the exiles in Bass Strait, found they were “a brave and patriotic people” who considered themselves to have been “engaged in a justifiable war against the invaders of their country”. Gilbert Robertson came to the conclusion that “they consider every injury they can inflict upon White Men as an Act of Duty and patriotism”.

JE Calder, another Tasmanian settler who thought deeply about the island’s war, wrote to a local newspaper in September 1831: “We are at war with them: they look upon us as enemies – as invaders – as their oppressors and persecutors – they resist our invasion. They have never been subdued, therefore they are not rebellious subjects, but an injured nation, defending in their own way, their rightful possessions which have been torn from them by force.”

Why is it so hard for today’s Australians to see what was clear to observers almost 200 years ago? Why is Tongerlongeter virtually unknown? There are no relevant monuments. His name has never been chiselled in stone, cast in bronze or placed on an honour board. No tree has been planted in his honour. No one tends his known place of burial. No official ceremony has ever been held to commemorate his struggles.

There is nothing in the Tasmanian landscape to remind locals or visitors that once an island of patriots fought a desperate war against an invader. Why ever is Tongerlongeter not one of Australia’s national heroes? It is hard to think of any historical figure more deserving of that honour.

The important role he played in Australia’s colonial history is, as we have shown, beyond dispute. He led the most significant Aboriginal campaign against the British invasion. He continued to play a leadership role in the life of the exiled community on Flinders Island until his premature death.

The campaign that he led had a large impact in Tasmania itself, and helped bring about major changes in British imperial policy, not as dramatic as the abolition of slavery, but of real importance to the indigenous peoples of the Empire.

The Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 and the recognition of Aboriginal rights on land held under pastoral lease right across the Australian colonies were innovations that continue to have relevance today. Although almost unknown, Tongerlongeter was without doubt one of the most influential leaders of Australia’s First Nations to have emerged since the British first invaded the continent 233 years ago.

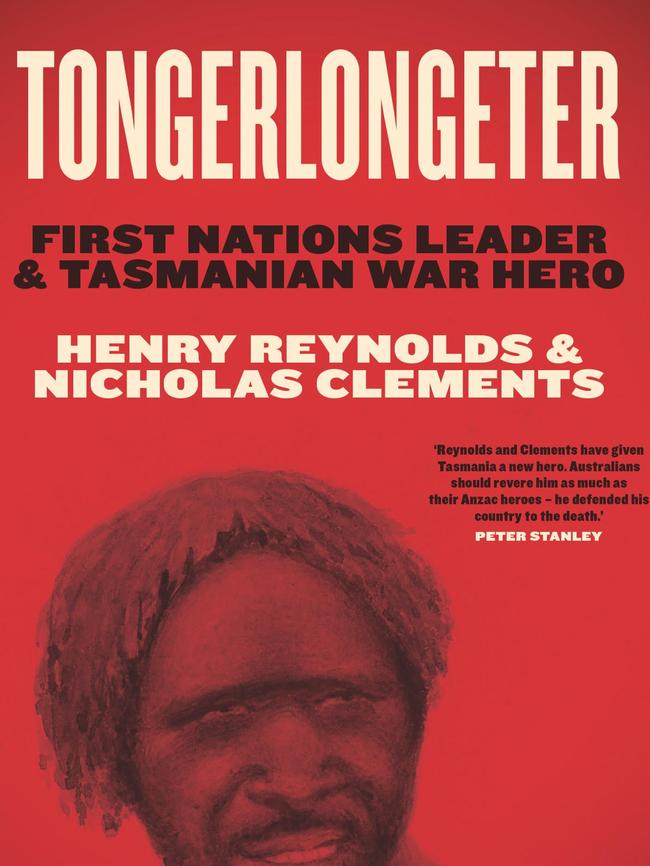

This is an extract from Tongerlongeter: First Nations Leader and Tasmanian War Hero by Henry Reynolds and Nicholas Clements published this week by NewSouth.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout