Robert Menzies’ home movies capture Australia at a ‘crucial time’

Footage shot here and abroad shows the 12th prime minister was a born performer.

In January 1941, Robert Menzies left for a four-month wartime trip abroad to London, Dublin, Ottawa and Washington to ensure Australia’s voice was heard at the highest councils of government. Before his departure from Rose Bay in Sydney aboard the Corinna seaplane, he packed a handheld movie camera.

Menzies was given the camera, which shot 16mm colour films, by his friend George Nicholas. These home movies allow us to look through Menzies’ eyes and see the places and people he met: the wreckage of London during the Blitz; Winston Churchill puffing on a cigar and feeding swans; candid shots of a young Princess Elizabeth.

The extraordinary films Menzies made during his two prime ministerships (1939-41; 1949-66), and his years in the political wilderness between them, include candid images of political and military leaders and a relaxed royal family, and provide glimpses into his home and family life in Melbourne and at the Lodge.

The story of Menzies’ movies is told in a new documentary produced by Sky News Australia for Foxtel and presented by John Howard.

“Menzies had taken his country to war after only 20 years since the most destructive war in all of human history, so he knew it was a dramatic and historic time, and this was his way of chronicling it and recording it,” Howard says in an interview with The Australian.

“What fascinated me was that this man was so good with the movie camera all those years ago and that it was colour when everything else was in black and white, and that it was at an absolutely crucial time for Australia.”

It is not the first time Menzies’ home movies have been presented on television but it is the first documentary that showcases them at length. The films were donated by Menzies’ wife Pattie to the National Film & Sound Archive in 1985. Menzies’ camera and brown leather case with “RGM” on the front is held at the National Museum of Australia.

The documentary, produced by Richard Andrews and Mick O’Donnell, includes extracts from Menzies’ 1941 diary, voiced by an actor, and additional historical footage. It also features interviews with Menzies’ daughter, Heather Henderson; granddaughter, Edwina Menzies; the chief executive of the Robert Menzies Institute at the University of Melbourne, Georgina Downer; and historian Anne Henderson.

Menzies was concerned that Australia’s interests were not given the attention they deserved in the British war cabinet. He was not being kept informed about war strategy or the deployment of Australian troops. He wanted Singapore reinforced. He had difficulties with Neville Chamberlain and thought matters would get only worse when Churchill succeeded Chamberlain as prime minister in 1940. This is what motivated the lengthy trip abroad.

Menzies stopped in Singapore, Jakarta and Bangkok, and had 10 days in the Middle East. He filmed aboard ships at sea and planes in the air. In the Middle East he is seen meeting, reviewing and addressing Australian troops, touring army hospitals and shaking hands with Thomas Blamey, the commander of Australian forces.

The movies show wartime London: the Palace of Westminster and Big Ben, double-decker buses, Buckingham Palace, bombed and burning buildings during the Blitz. He meets the Churchills at home and visits former prime minister Lloyd George. Often politicians, civil servants, ambassadors and military figures stand awkwardly, smile and talk among themselves while being filmed.

The images Menzies captured of the royal family, including Princess Elizabeth packing up a picnic, are so valuable that a copy has been deposited in the Royal Archives. Several documentaries about Churchill also have used Menzies’ home movies.

“What stands out to me is the remarkable period of time that the films covered,” Howard says. “It is rare that you have a first person account of such a historic period in the history of a nation via a person having filmed it.”

Menzies travelled on to Canada, where he was filmed meeting RAAF trainees. He also met prime minister Mackenzie King. He went to the US to meet Franklin D. Roosevelt and filmed the Capitol and the White House, a nearby baseball game, the Supreme Court, the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial.

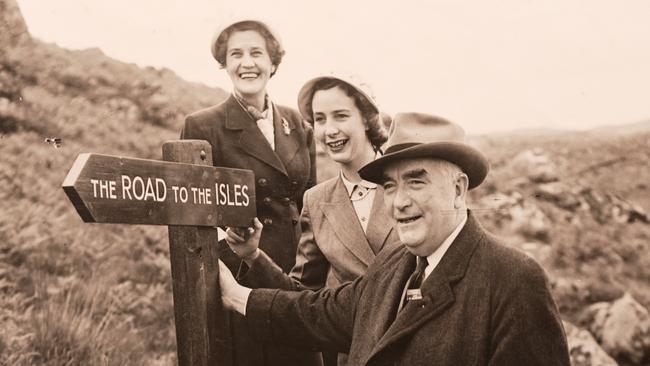

In 1948, as opposition leader, Menzies documented his journey to England that begins with Heather and Pattie throwing streamers from their ship to the wharf below. On board, we see Heather playing games and dancing above deck. The family travels around London, sees Cambridge University and visits Churchill at Chartwell, who was also in the political wilderness and yet to return as prime minister.

Another reel from Menzies’ 1948 trip to Europe shows him watching the cricket at Lords and visiting post-war Berlin, strewn with rubble, and includes footage of the sun set behind the Brandenburg Gates.

A third reel has the unfurling of Menzies’ certificate granting him the freedom of the city of Edinburgh and meeting William Birdwood, who commanded Australian troops at Gallipoli.

Menzies often set up a projector and screen in the opposition and government party rooms in Parliament House to show colleagues his home movies. He even screened the films for King in Canada. After dinner at the Lodge or in retirement in Melbourne, he would crank up a projector and share his films with friends and family.

One of the projectors is part of the collection of the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House.

There is no sound to accompany the pictures; they are silent movies. Menzies not only recorded people and places – with the camera next to his eye as the viewfinder was through the handle – he also advised Kodak on how best to develop the film and often edited the reels himself. Title cards were inserted by Menzies to describe scenes. One card prefacing a scene with Churchill reads: “Just to prove that I met him.”

Menzies was not just director, editor and producer, he was often the star. A born performer who could dazzle crowds with his oratory and bring them to laughter with his cutting wit, he wanted to be on-screen too. Menzies was a politician who understood the dramatic virtue in politics. He made sure he was in front of the camera as well as behind it.

“He had a curiosity for the UK but I also think they speak to the great thespian touch he had,” Howard says. “(The movies) tell us that he had a curiosity for things beyond politics (and) always remembering the political significance of something. He was a great actor. As a politician, you have got to have a certain thespian capacity.”

When the coronation of the Queen took place at Westminster Abbey in 1953, Menzies was there with his camera. His films show the monarch arriving in a horse-drawn carriage, the ceremony and procession. But some of this footage, like others, was taken by his personal secretaries.

On that same trip, Menzies filmed Churchill looking awkwardly and amusingly into the camera, playing fetch with a dog and walking with Pattie at Chartwell. Menzies and Churchill were now well acquainted, even admiring friends.

There is a naval review, including HMAS Sydney, at Spithead in Hampshire. And later, on that same reel, Menzies filmed snow falling at the Lodge in Canberra.

When the newly crowned Queen went on her coronation tour the following year, Menzies (or his personal secretary) was on hand to film her opening the Victorian parliament, waving to crowds at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, watching horse racing at Flemington and dedicating the Shrine of Remembrance.

This new documentary also takes viewers inside the Menzies family home in Kew, Melbourne, where they lived from the 1920s to the ’40s. This provides another valuable insight into Menzies, Pattie and children Heather, Ian and Ken. Menzies filmed his family at home, on holiday and celebrating birthdays, as well as Heather’s wedding to public servant Peter Henderson in 1955.

These films constitute an astonishing record made even more incredible because they were taken by an Australian prime minister. They also tell us much about Menzies himself.

He had a good eye for filmmaking and enjoyed it as one of his hobbies, along with reading books, writing verse, and watching cricket and football.

Having curated an exhibition on Menzies, made his own documentary and written a book on the Menzies era, Howard venerates his predecessor’s political skills and policy achievements. Howard says Menzies is “the greatest political orator” he has heard, respects the consistency of his values and admires his resilience.

Howard saw Menzies speak during the 1955, 1958 and 1966 election campaigns. He met Menzies just once – at the Lodge in 1964, when he was invited for drinks during a meeting of the federal council of the Liberal Party. “I do remember him mixing a martini,” Howard recalls. “He dropped an ice cube and chased it across the floor. He was a big man, but he caught it and picked it up, and it went back in the drink. I don’t think anybody suffered as a consequence.”

That lengthy 1941 trip, chronicled by Menzies on film, was ill-fated. Pattie warned him to expect “trouble” if he went abroad. His colleagues had grown restless, and some treacherous, at home. He lamented having to “play politics” on his return. He resigned three months later, having lost the confidence of his party.

But the movies Menzies made that year, and in subsequent years, survived and remain his gift to history.

Troy Bramston is the author of Robert Menzies: The Art of Politics (Scribe). The Menzies Movies premieres Wednesday, May 18, at 7.30pm AEST, On Demand on Foxtel and on Fox Docos.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout