NDIS rules fuelling surge in autism kids as doctors diagnose more severe cases in bid to help families

Children are being diagnosed with more severe autism than their characteristics warrant to give them a greater chance of securing a place on the NDIS, experts warn.

Children are being diagnosed with more severe autism than their characteristics warrant to give them a greater chance of securing a place on the NDIS, experts warn, boosting participant numbers and putting further pressure on the $34bn-a-year scheme’s financial sustainability.

The eligibility requirements for the National Disability Insurance Scheme are affecting how autism is being diagnosed as families and clinicians look to navigate the best support services for children, they say.

Andrew Whitehouse, professor of Autism at the Telethon Kids Institute and the University of Western Australia, said: “Clinicians and their families are regularly faced with a truly vexing conundrum, which is: should a child be given a diagnosis even if they don’t meet the criteria for autism, because it is the only way they will receive support.

“It is without question that clinical behaviour has become biased towards making certain levels of an autism diagnosis in order to provide families a better chance at receiving the support they need through the NDIS.”

Autism Spectrum Disorder ranges from people who need minimal support to those requiring 24-hour care. It most often manifests in the early years.

Under current NDIS guidelines autism is categorised into three levels of severity, with levels 2 and 3 “being likely to meet the disability requirements” for entry onto the scheme.

“This has led to an ‘all or none’ thinking which hangs in the background of diagnostic assessments,” Professor Whitehouse said.

“I’ve had many clinicians say to me they have not diagnosed someone with level 1 autism for many years – simply because it does not provide that family with a good chance of receiving the support they need through the NDIS.”

Paediatrician Gehan Roberts – the immediate past-president of the Neurodevelopmental and Behavioural Paediatric Society of Australasia, the peak body for doctors who care for children with developmental disorders – agreed there was an issue with diagnosis-based eligibility for NDIS funding support.

“It’s an uncomfortable space. As a clinician seeing someone one-on-one, you want to advocate for what’s best for the child,” Associate Professor Roberts said.

“On the other hand you want a rigorous evidence-based approach where a diagnosis is not made on the basis of enabling access to funding.”

The dilemma for clinicians and families of young people with neurodevelopmental issues is there is too little support available apart from the NDIS.

NDIS Minister Bill Shorten describes the scheme as “the only lifeboat in the ocean” after its creation saw other service providers including the states and schools vacate the field in terms of offering support to children with psychosocial challenges, and people with disability in general.

Mr Shorten says the scheme as originally designed wasn’t meant to cover everyone with a psychosocial illness, only the most severe. Yet a lot of states folded their mental health programs into the NDIS. “The Albanese Labor government is the proud defender of the NDIS and we want to make sure every dollar of the scheme gets to those who need it,” he said.

“We are open to looking at earlier screening for autism in infants and very small children so they can get the early intervention they need to flourish and find a path to independence.”

The NDIS is anticipated to cost the budget $34bn in 2022-23, rising to $90bn in the next decade. The number of children entering the NDIS with autism is driving overall scheme numbers, and cost, rapidly higher. And once they are in the scheme, very few exit.

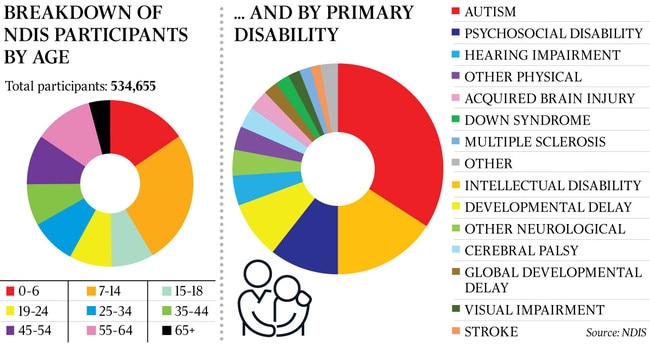

There are 92,000 children aged 0-6 on the NDIS, and another 140,000 aged 7-14. More than half (54 per cent) of the 266,000 participants aged 18 and under have autism and 20 per cent have developmental delay. About one in 10 of all boys aged 5-7 are now on the NDIS, along with 4 per cent of girls the same age. They are the fastest-growing category of participants in the scheme, which now numbers more than 570,000. Of the 20,477 NDIS plans approved in the December quarter, 9813, or 48 per cent, were for children younger than seven.

For about a third of NDIS participants, autism was their primary diagnosis, by far the biggest category. Packages range from a couple of thousand dollars a year to provide services such as speech and occupational therapy to six-figure sums for those who need 24/7 support.

Mr Shorten last year commissioned a review of the NDIS, due to report in October, which is examining its design, operations and sustainability. It is understood eligibility is a key focus.

Jim Mullan, chief executive of autism advocacy group Amaze, said the number of children coming onto the scheme in recent years “can’t be explained by the traditional view of prevalence rates in the population”.

“There also appears to be geographical variations, which may suggest that the way the diagnosis guidelines are being interpreted may be varying across the different regions,” Mr Mullan said. “For families, the NDIS is a gateway to supports for their child’s early development, which is often the primary factor in seeking a diagnosis. If you’re a clinician in the situation where that’s the case and no other supports are available to the child, you’re caught on the horns of an ethical dilemma.”

Associate Professor Roberts said a common situation was where a young child with developmental issues who has been receiving support through the NDIS’ early intervention program, which doesn’t require a formal diagnosis, such as autism, approaches the age of seven. “Parents are often told by disability service providers that NDIS services will end for their child once they reach seven years old if they don’t have a diagnosis of a disability,” Associate Professor Roberts said.

“If they don’t have this evidence, they will be left to navigate seeking support through the private, community or education system.

“To be eligible for the NDIS, they need to demonstrate their child has a ‘severe and permanent’ disability. Parents often wonder if a child with learning difficulties or ADHD will qualify for NDIS support: they don’t.

“For children without a physical disability, the commonest diagnoses that are eligible for support are intellectual disorder, diagnosed via cognitive (IQ) testing, or ASD. And for ASD the situation becomes murky.”

Associate Professor Roberts said NDIS eligibility for ASD effectively hung on a clinician’s diagnosis of either Level 2 or 3 severity. “When funding access is based on arbitrary lines in the sand like it is currently, prevalence of level 2 and 3 ASD diagnoses increases and level 1 plummets,” he said.

“As a healthcare provider, we go into bat in an advocacy role for our patients. If a family with no other means to access support has been told by a disability service provider there’s no other way it can provide support services other than through the NDIS, that’s when the pressure comes on the clinician to make a diagnosis at a level that will allow services to continue.”

Professor Whitehouse said he didn’t blame clinicians or families for wanting to do the best by a child.

“To be clear, these children need to be supported, and no blame whatsoever should be placed on parents and clinicians,” Professor Whitehouse said.

“However, our health, disability and education systems must adapt to provide the necessary support to all children, irrespective of their diagnosis.

“The purpose of a diagnosis is to provide understanding to the person and their loved ones, and to inform people about how best to support them. But to use diagnosis as an eligibility requirement means families are forced to jump through hoops at considerable emotional and financial cost, when all they are seeking is an urgent path to support their child.”

Professor Whitehouse said the future of the NDIS might depend on addressing issues around autism. “The NDIS is there to support those who need it the most, and it is clear that we need to more clearly define that boundary in order to keep the NDIS sustainable,” he said.

“But in doing that, we need other systems – such as state-based disability and education systems – to reinvest in this area, so that children not meeting criteria for NDIS still get the support they need. We should have no child left behind.”

Mr Mullan said the NDIS must be sustainable and available for those who needed it, but opportunities needed to be created for those who aspire to, and are capable of, life outside the scheme.

“The original design of the scheme envisaged that people could move in and out as their care needs changed over their lives,” Mr Mullan said. “The presumption behind this is that other pathways would be available outside the scheme to give them confidence to do that, but that isn’t happening. So it’s a cumulative effect. The NDIS is not designed to carry all the cost and all the weight of this challenge, which at the moment to a large extent it does.”

Associate Professor Roberts said that while the NDIS was fit for purpose for adults whose disability was fixed, it was harder to retrofit for young people continuing to develop over time.

“Ideally, early intervention wouldn’t stop at age seven, when families are required to either exit the scheme or accept a lifelong disability diagnosis,” he said.

“There might be stages as they grow older where they need fewer, or even no supports, and stress points when they need more supports: the system should be flexible enough for them to have a soft entry and exit for the times they need help.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout