Mortgage pain: 150,000 households to tip over $95bn cliff

Tens of thousands of homeowners on fixed rate mortgages are being hit by massive jumps in the mortgage repayments each month as their fixed rate terms expire.

Nearly 150,000 households on cheap fixed-rate loans risk falling off a $95 billion refinancing cliff over the next three months, as the nation hits the peak of the mortgage shock and the Reserve Bank’s rate hikes show their full economic power.

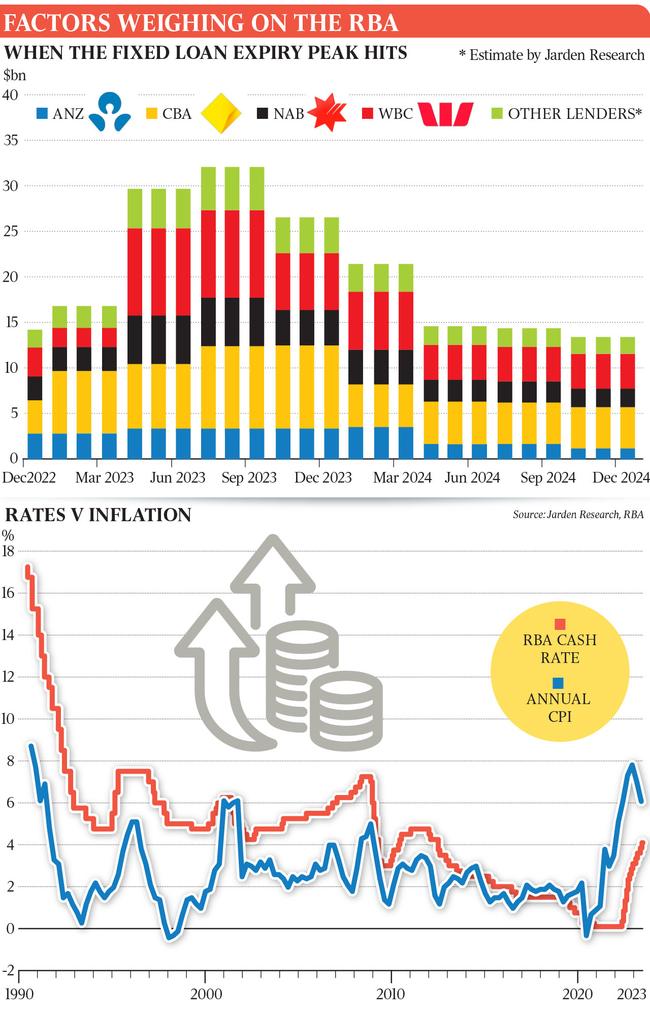

Ahead of the RBA board meeting on Tuesday to discuss whether to raise the cash rate for a 13th time since April last year, The Australian can reveal that $32bn of mortgages will refinanced each month in the September quarter.

For borrowers coming off fixed rates, the repayment on a $750,000 mortgage set at 2 per cent is set to balloon from $3180 a month to $4830 a month. This is an increase of more than 50 per cent overnight assuming a new rate of 6 per cent.

The new data came as Anthony Albanese returned to parliament on Monday after a six-week winter break to face an assault on cost of living from both Peter Dutton and the Greens.

The Prime Minister refused on Monday to consider the Greens’ demand for a freeze on rents to push his $10bn housing fund through parliament, or to accept the Coalition’s pitch to ditch the $40-a-fortnight JobSeeker rise and instead allow welfare recipients to pocket up to $300 in earnings without being booted off the payment.

Instead, Mr Albanese pointed to Labor’s ballooning $20bn budget surplus and his previous cost-of-living support in defence of his government’s approach to cost of living.

“We do have a plan to combat inflation,” Mr Albanese told parliament. “It is about turning the $78bn deficit into the first budget surplus in 15 years. The second is providing cost-of-living help that supports household budgets without adding to inflation. And thirdly, investing in supply chain challenges.”

Opposition Treasury spokesman Angus Taylor questioned why the government used old figures in the inaugural wellbeing budget to claim mortgage holders were better off than two decades ago.

“Why is the government so out of touch?” Mr Taylor asked.

Jim Chalmers said he acknowledged that small businesses were feeling the pressure of higher interest rates, but declared the biggest challenge in the economy was tackling inflation.

“The number one priority of this government … is getting on top of the inflation challenge and rolling out cost-of-living relief for Australians doing it tough,” Dr Chalmers said.

In 2021, Australians rushed to lock in historically low fixed mortgage rates of 2 per cent or below, with the share of borrowers taking out such loans quadrupling to 80 per cent.

RBA analysis has estimated that by the end of 2022 there were roughly 800,000 households on fixed-rate loans who were yet to pay a cent more for their loans, despite the Reserve Bank over the past year delivering the most aggressive series of rate hikes in a generation. Jarden chief economist Carlos Cacho said analysis showed that $32bn in fixed loans would expire in each of the three months to September – the peak rate of a roll-off to variable loans that would total nearly $550bn over the 15 months to March 2024.

Mr Cacho said the hundreds of thousands of households still on pandemic-era fixed-rate mortgages meant “there is still a tightening policy coming in the next six months, even if the RBA sits on its hands”.

Only about 75 per cent of the impact of the dozen rate hikes since the rate hikes started in May 2022 had hit borrowers, he said.

Mr Cacho said the recent run of economic data pointed to an RBA pause on Tuesday, and that he now had less confidence in his forecast that rates would reach 4.6 per cent by November.

NAB chief economist Alan Oster said the number of households rolling off ultra-cheap home loans in the second half of this year would be double the number in the first half.

Mr Oster said it was always difficult to judge when rate hikes would bite, but the overhang of fixed-rate mortgages made it especially hard to predict how deep the downturn in spending would be. “A lot of this worries me, as I’m old enough to have been in the federal Treasury in the late 1980s, when we kept increasing rates and nothing happened – and then something happened,” he said. “We are forecasting no growth in consumption in the second half of this year, and not even sure you would get in the June quarter.”

The extent of the bill shock facing tens of thousands of Australians comes ahead of the Reserve Bank’s cash rate decision on Tuesday, which economists believe is finely balanced between a 13th rate hike and a second straight decision to pause at 4.1 per cent.

While a slim majority of analysts tip a 0.25 percentage point rate rise on Tuesday, a faster-than-expected drop in inflation through the recent quarter and a large fall in retail spending for in June has led investors to cut back the probability of a rate rise to under 15 per cent.

The RBA board has become increasingly aware of the risks of pushing rates too high after delivering the most aggressive monetary policy tightening since the 1980s in its battle to bring inflation back under control.

With the economy decelerating sharply at the start of 2023, the central bank believes it has already pushed the cash rate to “clearly restrictive” levels.

But the historically large proportion of borrowers who snapped up super-cheap fixed-rate loans during 2021 has delayed the pass-through of higher rates to interest repayments and complicated RBA governor Philip Lowe’s task of navigating a “narrow path” to taming inflation without sending unemployment sharply higher.

Dr Chalmers last week said the 2022-23 surplus would come in “north” of $20bn, but added that the government was not working on any additional support for struggling households, although he also said an improved fiscal position would allow for more relief in “future budgets”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout