Migrant intake ‘not helping housing crisis’

A leading economist has warned that addressing the nation’s housing crisis cannot be achieved without slashing the country’s record migrant intake.

Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil says Labor’s upcoming migration strategy will not address the issue of the pace of population growth, as a leading economist warned that the country’s record migrant intake would need to be slashed to solve the housing crisis.

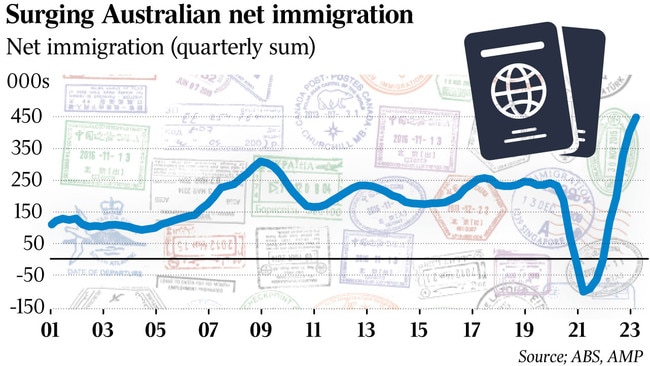

Amid growing concerns that the breakneck rate of net migration has exacerbated the nation’s housing crisis, AMP chief economist Shane Oliver called for annual net migration levels to be more than halved to 200,000 people – versus a likely 500,000 people in the year to June – for the country to have any hope of easing a chronic lack of suitable housing.

Dr Oliver said a broad consensus had emerged among policymakers, economists and bureaucrats that boosting housing supply is the best way to address plunging homeownership rates over recent years, and to take the heat out of soaring city prices that have sent young families fleeing overpriced markets such as Sydney.

But as rental vacancy rates drop to record lows and property prices reignite, the “debate about how immigration contributes to this issue is often lacking”, he said.

“Much of the focus has been on grants and other means to make it easier for first-time buyers to get a loan or on rent subsidies,” Dr Oliver said.

“But of course, this just boosts demand, making affordability worse.

“In recent times, there seems to be more recognition of constraints on the supply side. But surging immigration levels could easily overwhelm these efforts and lead to an even worse situation.”

Recent international arrivals data suggest net migration could reach 500,000 or more in the past financial year, or 100,000 more than projected in the May budget.

The Review of the Migration System, led by former Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet secretary Martin Parkinson and delivered in March, recommended that, longer-term, there was a need for a migration target.

That report found that Australia’s “approach to migration planning hasn’t properly accounted for the impact of large and uncapped temporary migration on infrastructure”.

“We need a long-term horizon that supports stable and predictable population growth and allows more effective planning of infrastructure, housing and services to meet the needs of all Australian residents,” it said.

Despite growing alarm over the record pace of migration at a time of worsening housing affordability, record low rental vacancy rates, and plunging home building approval numbers, Ms O’Neil said “what I want Australians to understand (is) this is actually not about how many people come to Australia … it’s about who”.

“It’s important to note that the overall effect of these changes will not be to increase migration in Australia. In fact, the effect of the (changes) will be to reduce the size of the system a bit,” she said.

While the structural fall in borrowing costs in recent decades has contributed to increasingly expensive housing stock, it has not been the prime determinant, as a number of countries have had low interest rates without unaffordable homes.

Dr Oliver said the deeper explanation is that “there has been a fundamental failure of housing supply to keep up with a surge in demand for housing that started in the mid-2000s with rapid population growth”.

He said immigration levels were “running well in excess of the ability of the housing industry to supply enough homes”.

He estimated that with an estimated housing shortfall of up to 280,000 dwellings by mid-2024 and a home-building supply capacity of 200,000 dwellings a year, immigration levels would need to be slashed to 260,000 people a year to prevent the housing crisis getting even worse.

“But if capacity is just 180,000 dwellings per annum … then immigration should be cut back to near 200,000 people a year.”

Mark Wright, who leads KPMG’s immigration practice, said there was merit in the government taking a longer-term approach to managing population growth, as long as it maintained a focus on meeting the nation’s shifting needs for different skills.

“Part of the reason migration often turns into a very charged debate is because we haven’t had a population policy, which is an obvious gap in economic planning,” Mr Wright said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout