Literacy gap ‘disadvantaging boys’, new NAPLAN data shows

One in five boys is semi-literate in high school, with boys twice as likely as girls to struggle with reading and writing at 15.

One in five teenage boys is semi-literate in high school, with boys twice as likely as girls to struggle with reading and writing at the age of 15, new data from a million Australian students reveals.

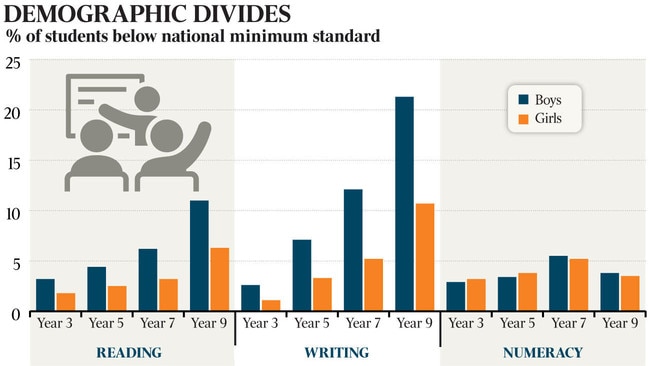

The 2021 test results for the National Assessment Program, Literacy and Numeracy, show one in 10 girls and one in five boys had failed to reach the minimum standard for writing after nine years of education.

Eleven per cent of boys and 6.3 per cent of girls failed to read at the minimum standard, sparking calls for intervention to prevent boys falling behind in their senior years of high school.

In writing, 21.3 per cent of boys and 10.7 per cent of girls fell below the national standard, meaning they could not punctuate sentences, spell most simple and common words, or write a story in paragraphs.

The Centre for Independent Studies’ research fellow in education policy, Glenn Fahey, said students should be screened for literacy problems when they started high school.

“I’d like to see the same level of attention applied to the gender gap in STEM applied to the gender gap in literacy,’’ he said.

“There is a lot of energy put into closing the gap between boys and girls in maths, but there is a much bigger difference in achievement in reading between boys and girls, and that flows through to all other areas of learning and opportunities in life.’’

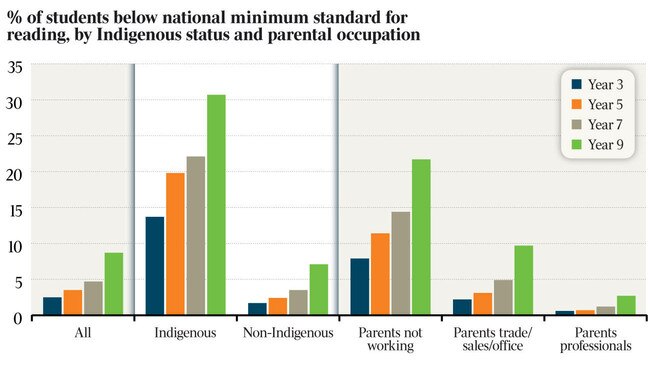

NAPLAN data also reveals a huge gap in achievement between Indigenous and other students, which grows wider as they go through high school: nearly one in three Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children cannot read properly in Year 9, compared with the national average of 8.7 per cent.

And students whose parents are unemployed are twice as likely to be unable to read at the required level in high school.

Even in Year 3, 8 per cent of children whose parents are not working fail to read to the minimum standard, compared with 2.2 per cent of students whose parents work in trade, sales or office jobs.

Mr Fahey said reading and writing were keys to learning other subjects, so poor literacy disadvantaged boys in higher education and the workplace.

“It puts them at a huge disadvantage when it comes to all subjects because once you’re in high school, there’s very little direct instruction in literacy,’’ he said.

“There’s a huge problem in the increased use of word-based assessment in mathematics, especially for boys.

“In some assessments, we see girls are improving not necessarily because their underlying numeracy skills are better but their comprehension and reading skills tend to be better than boys’.’’

Students in Year 9 are supposed to be able to interpret a labelled diagram, find information in a text and identify the main idea of a paragraph, but the national reading test reveals too many are lagging in literacy by the time they start senior high school, damaging their study and job prospects.

Primary students’ reading skills have improved over the past decade, as more schools switch back to phonic-based instruction to ensure children can learn to read by sounding out letters instead of memorising words.

The proportion of eight-year-olds struggling to read has halved since NAPLAN tests started in 2008. Data from the May 2021 tests of one million students from 9000 schools, released on Wednesday, shows 4 per cent of Year 3 students failed to meet minimum reading standards in 2021 compared with 8 per cent in 2008.

Reading expert Jennifer Buckingham, the founder of the Five from Five project who chaired the federal government’s expert advisory group on a Year 1 literacy check, hailed progress among younger students, saying phonics-based reading instruction was helping children learn to read, although boys tended to read less than girls.

“The more kids read, the better they get at reading,’’ she said.

“Boys just don’t read as much as girls so they’re not getting the practice.’’

At Fairfield West Public School in Sydney’s west, where one-third of the 600 students are from refugee families, students are flourishing in reading.

Principal Genelle Petruszenko said the school used needs-based funding to employ expert teachers and teacher aides, and used phonics to teach children to read.

The school also uses “explicit instruction’’, so teachers give detailed, guided and tailored instructions to children and then check their learning.

“Many of the children have never been to school before and sometimes their parents haven’t either,’’ Ms Petruszenko said.

“They want to do well – part of having freedom and choices in your life is to be able to read and write and do mathematics.’’

The NAPLAN test results reveal boys are more likely than girls to excel at maths across all year levels, although the gap is much smaller than for literacy.

In Year 9, just under 4 per cent of boys and girls failed to reach the minimum standard in numeracy, while 8.1 per cent of boys and 5.4 per cent of girls excelled at the highest level.

Acting federal Education Minister Stuart Robert said results confirmed there was “no drop’’ in student performance despite the pandemic.

Federal Minister for Regional Education Bridget McKenzie said “sadly, there continues to be a gap in performance between city and regional students’’.

The Australian Curriculum and Assessment Authority, which runs the NAPLAN testing, said Covid-19 lockdowns and disruption had had no “statistically significant impact’’ on student results.

“The NAPLAN results for 2021 indicate that when compared with 2019 – the last NAPLAN pre-Covid – achievement in numeracy, reading and writing remained largely stable at a national level for all students,’’ ACARA chief executive David de Carvalho said.

The 2020 test was cancelled because of Covid-19.

Australian Education Union federal president Correna Haythorpe called for more funding for public schools, which educate most of the nation’s disadvantaged students.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout