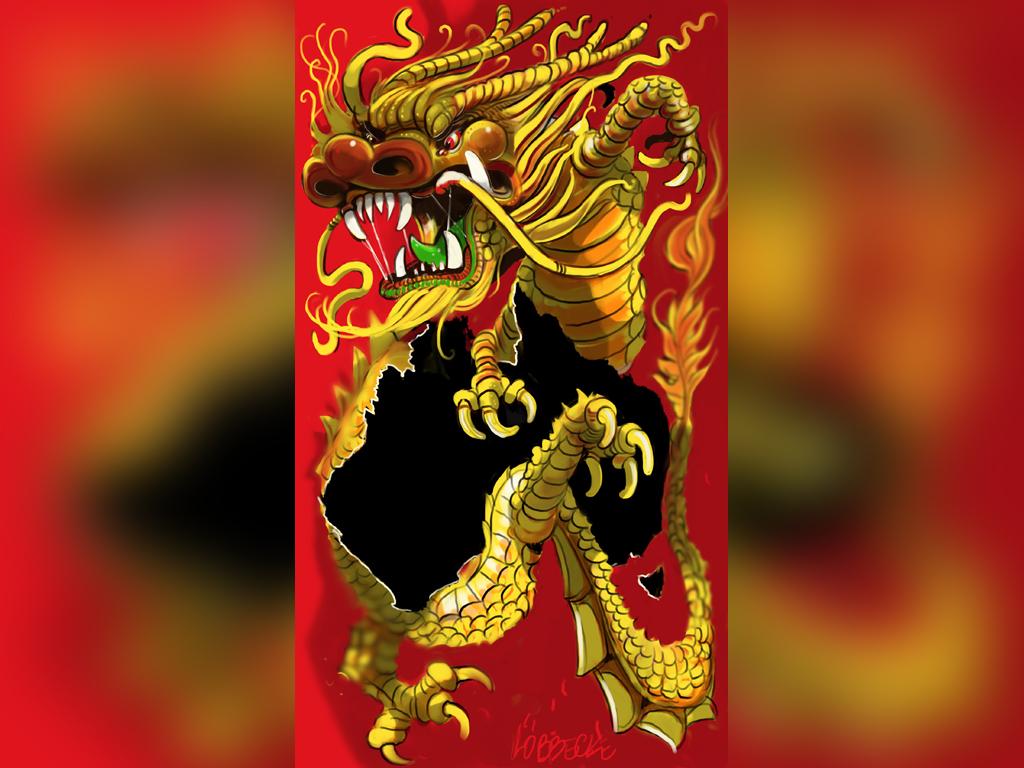

Left demands global action but cringes before Beijing

The China debate is playing out through a tired and lazy cultural cringe that infects our politics, particularly on the left.

To advance our nation’s interests it is vital to understand its strengths and vulnerabilities, and to have a firm sense of our place in the world along with that of other nations. In my time working with then foreign minister Alexander Downer he bristled at the description of Australia by politicians and academics as a “little country” or even a “middle power” and insisted we were, in fact, a “significant” country.

Speaking to Asialink in Melbourne in December 2005, he confronted this head on. “We’re not a little country — we’re a country with significant strengths and resources,” he said, noting our distinct characteristics and values. “Australia is a significant country, with global interests and not just a regional player.”

This is more than rhetoric — the UN has 193 member nations and Australia ranks as the 14th largest economy, the sixth largest land mass, with a population ranked about 50th and a military assessed as the 15th most powerful. Look at it this way: on such metrics, we sit in the 90th percentile of nations.

Forgive me for harbouring an old-fashioned but well-founded sense of national pride, but it seems to me that people who sit in our parliament ought to share this sense of place. We are, after all, one of the world’s oldest and most successful democracies, with more than our share of Nobel prizes, Olympic medals, Bookers, Oscars and Grammys.

But when Labor frontbencher Andrew Leigh was asked this week why we should not take up our trade disputes directly with Beijing rather than defer immediately to the World Trade Organisation, we got one of those cringe-worthy moments. “But what’s the alternative for a country that makes up 0.3 per cent of the world population?” whined Leigh. “If it comes to muscular one-on-ones, then a country the size of Australia will lose every time.”

This exposes a key problem with our foreign policy debate — sure, there is ideology at play, commercial interests, and more than a little politics, but the core dilemma is that inferiority complex. The same people who argue we should lead the world on climate change or spit in the face of Donald Trump go wobbly when we dare put our case to China. And it is not all about might, because the same protagonists also run anti-Australia lines when they come from Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur or even Dili.

The predisposition to take the foreign side against Australia has become a defining characteristic of the left. For much of last century this might have been explained in ideological terms, fuelled by anti-American fervour.

Now, we can see the Cold War hangover but it is infused with a dose of 21st-century identity politics. This is the self-loathing of those who prefer shame about a white, Christian and Anglo nation in the wrong place at the wrong time, rather than pride in a multicultural success story, founded through British institutions in a land of indigenous heritage, that helps to forge a better world.

Leigh told the ABC that Scott Morrison should not have suggested an independent investigation into the origins of a pandemic that has killed 300,000 people and sideswiped the global economy. “When you act on your own,” said Leigh, “you do find yourself being back in that realm that John Howard found himself in with the infamous deputy sheriff statement.”

This “deputy sheriff” taunt was used by former Labor foreign minister Gareth Evans as well. Back at the Chinese embassy, it would have brightened the spirits of the ambassador, Cheng Jingye, who finally had a pleasing cable to send back to Beijing.

Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews boasts about his state’s commitment to China’s Belt and Road initiative, an international infrastructure and influence scheme that our federal government — which has carriage of foreign relations — has chosen to avoid. The states need to stay out of such matters and stick to their constitutional priorities.

Just weeks ago Cheng was threatening us for raising a COVID-19 investigation. “The tourists may have second thoughts,” he told The Australian Financial Review. “Maybe the parents of the students would also think whether this place, which they find is not so friendly, even hostile, is the best place to send their kids to. So, it’s up to the public, the people to decide. And, also, maybe the ordinary people will think why they should drink Australian wine or eat Australian beef?”

China has since banned imports from four of our abattoirs, hiked tariffs on our barley and heightened post-pandemic fears for our wine, tourism and university sectors. With this unfolding, Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk said she was worried about a trade war and would write to the federal government to urge it to avoid one.

Say what? Is Australia the problem here? At least West Australian Premier Mark McGowan, despite mouthing similar concerns, had the good sense to lobby the Chinese consul-general as well as Canberra. Business leaders with deep commercial links to China, such as Kerry Stokes and Andrew Forrest, constantly urge Canberra to button up. What price our national values?

This is not to underplay the trade concerns. But if we do not want to be subservient and eternally bullied, we need to stand up for ourselves.

The contradiction inherent in the interventions of Leigh and Evans is that they claim when Australia independently speaks for national and global interests we are seen as a lapdog of the US. But presumably if we hide behind the skirts of the Statue of Liberty, the G20 or UN, and go along with whatever multilateral entreaties emerge, we will be perceived as independent. This is a nonsense.

As a former US ambassador, director-general of ASIO, secretary of Defence and of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Dennis Richardson has a broader and deeper grasp of these issues than most. He told me recently on Sky News that Cheng’s threats were “blunt, unnecessary and foolish” and the government had a “legitimate interest” along with the rest of the world in a proper inquiry, which would happen only with “a lot of behind-the-scenes activity”. He said we were “not an outwardly patriotic country” but when threatened we were “pretty determined” and “Australia is not going to be intimidated by threats of that kind”. Let us hope he is right.

The previous month I interviewed former Labor foreign minister Bob Carr who, to be fair, backed some sort of inquiry but he quickly segued to America. “I think there are lessons to be learned all over, I mean at the very start of this, when we knew what it was, we were dealing with a virus, Fox News, a vital media outlet in the US, was saying this was a conspiracy and we had … a US President who was getting up in his very entertaining press conferences saying it was no more dangerous than the seasonal flu.”

This was a bizarre attempt to draw equivalence between China’s dastardly denials — allowing a virus to spread around the world for at least a month before issuing alerts — and the US which, like many countries, was caught short, underestimating the seriousness of the pandemic, partly because of Beijing’s deceptions. Such diversions serve no purpose other than to ease pressure on China. Thankfully, the Australian Workers Union is speaking sense, writing to the Prime Minister urging him to resist Beijing’s bullying. This unusually useful union intervention seems to have injected a bit of titanium into the spines of some Labor MPs, while creating internal divisions.

Beijing will be pleased at some aspects of our debate: the US alliance raised as a bargaining chip; Labor and the unions splitting; big business cleaving away from the Coalition; and the states taunting Canberra. It is not too much to ask for all our politicians to readily argue a pro-Australian case.

“The fault here is with Beijing and the Chinese government,” says Australian Strategic Policy Institute analyst Michael Shoebridge. “China repressed information, prevented action and didn’t ask for international help and they inflicted suffering and death on their own people and the rest of the world — that’s why they don’t want this inquiry. But that’s exactly why the Prime Minister was right to call for it.”

The China debate is playing out through a tired and lazy cultural cringe that infects our politics, particularly on the left, and is based on an unwarranted inferiority complex that is deeply embedded in our cultural life. This makes it all too easy for some to slip into a kowtowing posture.