Budgets reflect government values and spending priorities, short and long term, within the amount of revenue available.

Of course, fiscal quantity and quality matter, but right now more spending on social programs and subsidies will stoke consumer demand, while supply-side expansion will take years to make a difference.

The Treasurer is right about the free-for-all Greens and their cavalier approach to promising the earth but never having to balance a budget in office.

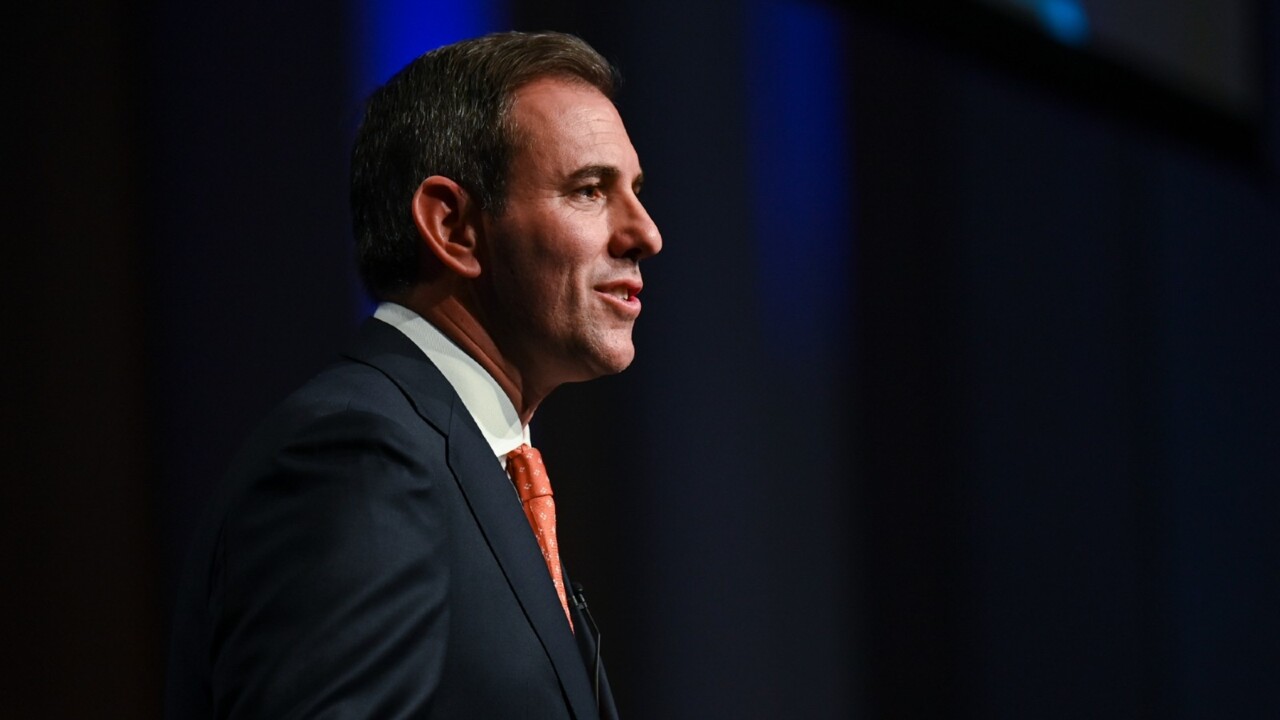

Yet he’s built a seasonal straw man by describing as “scorched earth austerity” calls for fiscal restraint at a moment when inflation remains too high and the budget is in underlying deficit for at least a decade.

Yes, as Finance Minister Katy Gallagher claims, some costs are “unavoidable” – like the pension in an ageing society and national defence in an era of geostrategic threats and realignment – but routine housekeeping expenses for IT upgrades and the like should not be used as cover for plain old fiscal backsliding.

After all, this is Jim and Katy’s third rodeo and they cleared out the stables in 2022.

Canberra’s footprint got much bigger during the Covid-19 health and economic emergency and it’s clear that the size of government is now larger than it was before the pandemic, and growing.

Federal spending as a proportion of the economy was just under 25 per cent in the decades leading up to the crisis, and it looks like settling at just over 26 per cent in the years ahead, because of the rising cost of the National Disability Insurance Scheme, health, aged-care, defence and debt interest.

That’s an extra $25-30bn of costs in today’s dollars.

What to do?

First, go for something strong, like imposing clear fiscal rules on a government in executive drift, rather than simply belting out the chorus line that the “budget is in better nick”.

That’s a cyclical quirk; it won’t last or escape the notice of global credit scrutineers.

In June 2022, a few weeks after the Albanese government was elected, Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy explained the long-run challenges facing the budget: spending was growing robustly, as was the burden of personal income tax, while productivity growth was stagnant.

Funding Labor’s future priorities in spending, Kennedy said, would come by either cutting existing programs or raising taxes, both of which require skill and voter assent.

The vast majority of government expenditure is subject to legislation, existing commitments or contracts, he said, so it’s critical to ensure existing and new programs on the government’s priority list are cost-effective.

In its first budget, the Albanese government cleared away some of the junk the Coalition had accumulated during its nine years in office.

But Labor has been on a mid-season bender, baking in forever spending programs in a whole range of areas off the back of the one-off boom in revenue.

With a federal election due this time next year, it’s reasonably safe to assume that even more spending is coming down the line for Labor’s signature Future Made in Australia foray and more generous social programs.

Again, that loose approach won’t help Michele Bullock and the Reserve Bank board to suppress homegrown inflation, which is running at 5 per cent compared with imported inflation at 1 per cent.

It will now take longer than necessary to bring inflation back to the 2 to 3 per cent target band, so interest rate cuts before the election are a fading hope.

The budget’s spending side is not only expanding in ambition but current programs are flabby.

Reining in the NDIS depends on luck, goodwill of the states and an accounting fudge for cost control over the medium term.

In its latest economic outlook, the OECD highlighted spending pressures from disability services as a clear and present danger to fiscal sustainability.

It requires wholesale reform.

Just as important is the long-term health of the budget.

What if our export prices, relative to import prices, tumbled back to where they were two decades ago?

Economist Chris Richardson doesn’t think that will happen, but estimates revenues would then be lower by around $100bn.

It’s what Canberra spends on defence, education and housing. It’s more than the GST take.

“It’s a reminder of the fragility of the budget over the long haul,” the astute budget watcher says.

And a sign of the fragility of Labor’s economic strategy.

Budgets are about choices and Jim Chalmers risks making some unhealthy ones next Tuesday that will put pressure on inflation and saddle the nation with forever costs, dud projects and higher debt.