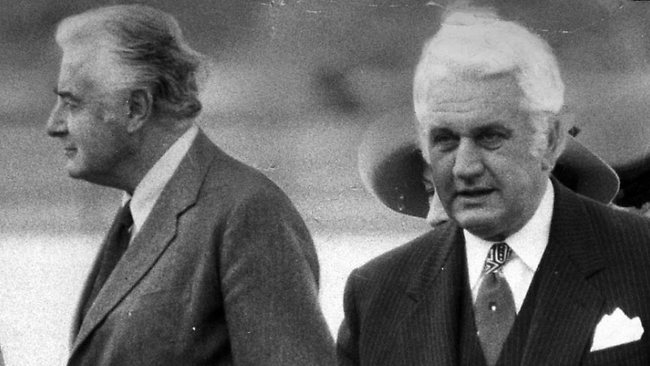

Kerr's second crisis

THE dismissal could have unravelled on the afternoon of November 11.

SIX days after the dismissal of the Whitlam government on Remembrance Day 1975, the secretary of the Attorney-General's Department, Clarence Harders, told John Kerr that his dismissal of Gough Whitlam was not justified.

Kerr convened a meeting at Government House on November 17 to revisit his dismissal of the government and the dissolution of parliament for an election. Joining Kerr and Harders at the meeting were caretaker attorney-general Ivor Greenwood and solicitor-general Maurice Byers.

According to Kerr's record of the meeting, Harders agreed "the reserve power of the Crown existed", but he also "thought a forced dissolution could only be precipitated in extreme circumstances and he said frankly that he did not himself believe that the circumstances in which I had acted were serious enough".

Kerr was agitated. The head of the Attorney-General's Department was telling him that he had made a mistake. The friction was obvious between the governor-general and one of the nation's most senior legal figures. Kerr went on the offensive.

"I said to him," Kerr writes, "I had to take the responsibility for exercising the discretion which only I possessed and the fact that there might be difference of opinion about circumstances in which it might be exercised was something about which I did not ask his advice or the advice of the law officers of the Crown."

Kerr knew that Harders and Byers had what he termed "grave doubt" about the existence and use of the reserve powers. At this meeting he tried to lock them into acquiescence of his dismissal decision.

Ironically, Harders's department had prepared a document on the governor-general's powers dated October 10, 1975. Marked in pen across the top are the words: "An important note". This paper concluded that in the event of supply being blocked, "examination of the possibilities would certainly not appear to be any ground for dismissal".

At the meeting on November 17, Kerr told Harders: "The law officers may argue (that) the reserve power of the Crown no longer exists." However, "I don't agree myself," he said, "and accordingly if that opinion came forward I certainly would not regard myself as bound by it."

Kerr tried to pressure Harders and Byers by referring to their advice on the afternoon of November 11, when they told him he could continue to exercise the reserve powers and accept Malcolm Fraser's advice to dissolve parliament for an election.

Kerr reveals that he asked why Harders was now arguing it was wrong to exercise the reserve powers whereas on November 11 he had only questioned it. "Harders then said," Kerr recalls, "he had not meant to be expressing approval of what I had done in the morning, as his own view was that things were not serious enough on 11 November for the exercise of the reserve power, but as I had done it I ought to go on to the end."

Kerr and Greenwood then turned up the pressure. They asked Byers and Harders "why, if they believed that the power to force a dissolution no longer existed, they had not said so on the afternoon of 11 November". Harders, according to Kerr's note, said "the power did exist" but again questioned "the seriousness of the situation". Byers said that the reserve power existed but expressed doubt over its use regarding "forced dissolutions".

This exchange revealed the extent of tensions engulfing the government after the dismissal, with the senior legal officers, Harders and Byers, convinced that the governor-general had misused his powers. It is also an insight into events on the afternoon of November 11 when there was, in effect, a second crisis.

The point is that Kerr's dismissal of Whitlam could have quickly unravelled. At the heart of the second crisis was Kerr's unfinished business: to ensure that Fraser fulfilled the terms of his commission to pass the supply bills and to advise that parliament be dissolved for an election.

Kerr was alert to the danger he faced. If supply was not secured and parliament was not dissolved, then his dismissal of Whitlam would be threatened. The governor-general wanted advice that afternoon to ensure his actions had authority and legitimacy.

The second crisis also exposes Whitlam's misguided response to the dismissal. If Whitlam had immediately turned his attention to denying Fraser supply, then Kerr's strategy could have been at risk.

Fraser was also aware of his vulnerability. That afternoon, as Fraser pressured the public service to prepare the legal instruments to dissolve parliament, Harders told him there was a question over the legitimacy of Kerr's strategy.

The trigger for the second crisis was the House of Representatives' no-confidence resolution in Fraser as prime minister. After Whitlam was dismissed at 1.10pm, he retired to the Lodge to eat a steak and consult with colleagues. There, he drafted a motion of no-confidence in Fraser.

At 2pm, the house resumed. There was no immediate mention of dismissal and Fraser did not announce that he was prime minister until 2.34pm. At 3pm, Whitlam moved a motion of no confidence in Fraser. At 3.14pm, the motion passed by 64-54 votes.

Kerr writes in a note that Whitlam phoned him. "He said that as supply had been granted (the Senate had voted to pass supply at 2.24pm) I should terminate the Prime Minister's commission and recommission him. He wanted to attend upon me to put this point of view." Whitlam said, "You saw Fraser before, so I suppose you will see me." Kerr told Whitlam that he would have to secure Fraser's approval for such a meeting. "I said I would speak to him and let Mr Whitlam know the position." The meeting never happened.

On the other side of the parliament, the Senate resumed at 2pm without the government leader, Ken Wriedt, or the manager of government business, Doug McClelland, knowing about the dismissal.

The opposition senators, however, did know.

A "note for file" prepared by the parliamentary liaison officer, MJ Hanson, described the pervading sense of "confusion" in the Senate.

At 2.20pm, Wriedt reintroduced the supply bills. In just four minutes they had passed with the support of both sides of the chamber. The Senate was then suspended.

Hanson's contemporaneous note outlines how Kerr's dismissal action could have been thwarted. He writes: "Had Senator Wriedt not proceeded with his motion and had the initiative for passing the bills been left to the Liberal-National Country Party senators, then it may have been possible for the Labor Senate to have delayed passage of the bills until the following day."

"This is because," Hanson explains, "the restoration of the bills would have been denied to the Liberal-National Country Party senators as they would not have had an absolute majority in the Senate (assuming that Senators Steele Hall and [Cleaver] Bunton would have continued to vote with the Labor senators)." In this situation, "The Speaker could then have informed the governor-general not only of the want of confidence motion in the new prime minister but also the fact that supply had not been granted."

But Whitlam never saw this critical point. He focused his attention on the house, believing that Fraser could not continue to govern without its consent. Critically, no senators were present at the Lodge to discuss strategy nor were any informed of the dismissal before the Senate resuming at 2pm.

The secretary of the Prime Minister's Department, John Menadue, had been called to the Lodge at 1.20pm by Whitlam.

According to a "note for file" prepared by Menadue, he was contacted at the Lodge by Fraser's office and told that the new prime minister wanted to see him "urgently". He left and arrived at Fraser's office at 1.50pm.

Menadue writes: "He (Fraser) informed me that he had been sworn as prime minister, and that he proposed to obtain passage of the appropriation bills through the Senate as quickly as possible, their presentation for royal assent in order that the parliament could be dissolved." Fraser, like Kerr, was focused on the supply bills in the Senate and the need to dissolve parliament quickly.

On returning to his department, Menadue was told by officials "that the normal procedures took about two days" to prepare bills for assent. But they did not have two days; they had two hours. Fraser was edgy, impatient and insistent. Soon after Menadue arrived back at his department, "Fraser rang and enquired about progress". He writes: "There were several urgent calls from Mr Fraser" within that two-hour period. Fraser told Menadue "it was essential" that all documents be with him by 3.40pm, in time for Kerr's signature at 4pm.

Harders arrived at Fraser's office at about 3.45pm and the papers were presented to Fraser. Fraser took Harders into an adjoining room. "He said that it was possible," Harders wrote in his note, "that the governor-general would wish to have advice regarding the resolution that had been adopted by the House of Representatives earlier in the afternoon expressing want of confidence in Mr Fraser." Fraser knew this could be a problem.

Byers had not yet arrived at Parliament House. But Fraser could not wait. He had to leave to meet Kerr. Harders went with him. They rushed through the corridors of Parliament House and outside to a waiting car. "The crowd was pressing around the car and the driver drove off immediately," Harders recalls.

He then indicated to Fraser that Kerr faced another delicate decision. Harders's note says: "On the journey to Government House I spoke to the prime minister about the point he had raised with me. I said that it appeared that the governor-general had acted on the basis that he had a reserve power, that the governor-general had previously exercised a discretion that he regarded as residing in him and that the question whether he should change his decision in the light of the resolution adopted that afternoon by the House of Representatives was one for the governor-general to consider, in the exercise of his discretion."

In short, Harders was telling Fraser that the transition of power was not yet a done deal. He was querying whether Kerr "should change his decision" given these events in parliament.

Arriving at Government House, Fraser went in to see Kerr alone while Harders made several calls, including to Byers. They discussed the impact of the house resolution and the "question" it raised for Kerr.

Meeting Kerr and Fraser, Harders reiterated his view to the governor-general and noted that Byers agreed with him.

But Kerr, from his notes, was firm in his own mind. He said that having exercised the reserve power to dismiss Whitlam, he was entitled to continue to exercise the reserve power "to sustain Mr Fraser in office and to get an election".

"I had a prime minister," Kerr said, "who did not have the confidence of the house but who was prepared in accordance with convention to recommend an election. This was pursuant to his earlier undertaking and I was prepared to accept this advice."

At 4pm, Kerr signed the proclamation dissolving parliament.

Kerr drew a strong lesson from this encounter - his scepticism about the law officers only deepened and he was convinced that his seeking advice from the High Court had been prudent and necessary.

"I believe that what happened in the afternoon of 11 November," Kerr concluded, "together with my other experiences of the law officers of the Crown, confirmed that it had been wise to get the Chief Justice's advice on 10 (November) as he was prepared to give it."

But Kerr was constantly seeking reassurance for his actions. In the afternoon of November 11, Kerr called Anthony Mason and told him the Speaker was waiting to see him to inform him of the motion of no-confidence passed by the house. According to Mason, he told Kerr to hold his nerve: "I said that the resolution was irrelevant as he had commissioned Mr Fraser to form a caretaker government for limited purposes to hold a general election."

Here was the "keystone" in what Kerr termed the "arch of advice" giving him the reassurance that he sought.

When Harders returned to his office later on the afternoon of November 11, the phone rang. It was Kerr. He rang through directly himself. "He referred to the resolution that had been passed by the House of Representatives," Harders wrote. "The reason for the call was not clear to me. So far as I could sense, however, the call was made for the purpose of asking me to recapitulate the advice I had given to him earlier in the afternoon at Government House."

In summary, Kerr's papers reveal the advice Harders gave on the afternoon of November 11 was that "as I had exercised the reserve power in the morning I could continue to exercise it". But Kerr was in error to believe that this meant Harders and Byers were endorsing the dismissal of Whitlam. They were not. And at the November 17 meeting, Harders told the governor-general to his face he believed the dismissal was unjustified at the time.