Julia Gillard: The prime of her life

Post-politics, Julia Gillard made a decision. The result is a model former prime minister of dignity and grace who has only risen in public esteem.

What Gillard decided not to do was incessantly propagate her own legacy, settle scores with former colleagues or become a self-righteous critic of her predecessors or successors. This would not be good for the nation or for her. It is a different strategy than that adopted by those who departed the nation’s top job after her.

The result is that Gillard is a model former prime minister of dignity and grace, generosity and courtesy, who has only risen in the esteem in which she is held by Australians, even among those who did not vote for her. Some of her erstwhile political opponents, including within Labor, admire the way she has conducted herself in post-political life.

“I did think carefully in the period after I left office about what I wanted to do, how I wanted to still contribute on the issues that mattered to me,” Gillard says in an exclusive interview.

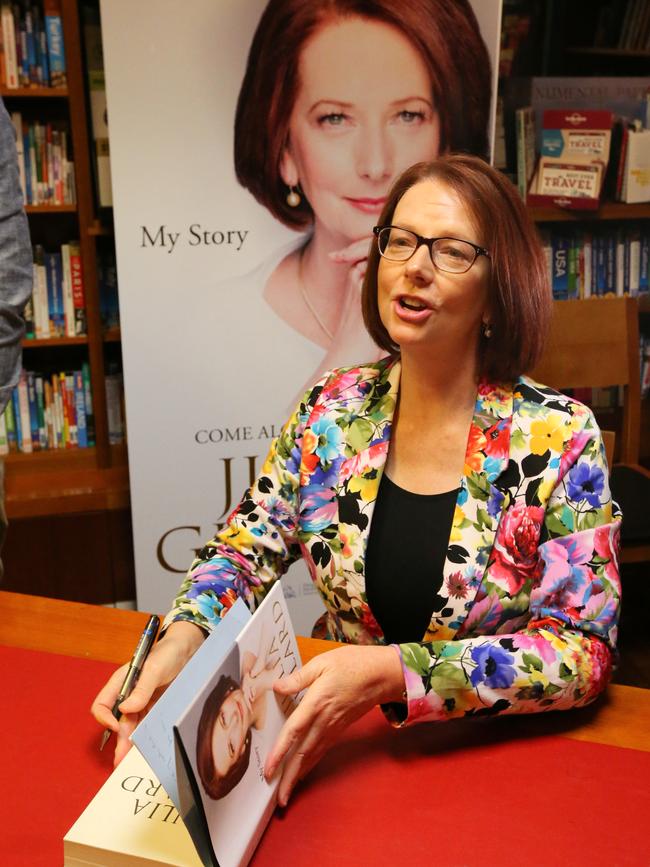

“I did want to have my say on the times that had been, and I did that predominantly through my book, and having had that say I didn’t want to be involved in day-to-day political affairs. I have been very rigorous about that.

“It has been good for my own sense of self and how I enjoy the world, not to be looking back and grinding my teeth or carrying on about something in the newspapers or something said in parliament. I don’t worry about all of that. I think that’s a better approach. It means I get more enjoyment out of my life. It gives me more space to do things that I care about. I think it’s just a healthier strategy all-round.”

There is no how-to guide for members of the Ex-Prime Ministers Club, a term Gillard laughs at. “There is no cubbyhouse. There is no secret handshake. There is no uniform or badge,” she says.

Sure, there is a pension and travel allowance, and an office with a few staff. But there is no US-style presidential library. Corporate, educational, community or other government roles are not always forthcoming. They don’t keep the title, unlike US presidents. What they do is, well, up to them. It is legitimate for former prime ministers to preserve their legacy. While their memoirs are of an uneven quality, they are nevertheless a welcome contribution to the historical record. Their thoughtful engagement in policy debates should be encouraged. They deserve respect and appreciation for their public service.

But when they become regular knockers, fault-finders and denigrators, they diminish themselves and the nation, and their interventions have less impact.

Rarely a day goes by without Kevin Rudd slamming Scott Morrison. Tony Abbott was often at odds with Malcolm Turnbull. Both Rudd and Abbott undermined their successors while they were in parliament. (Abbott has largely shunned the limelight since the election last year.) Turnbull has lashed the Morrison government on energy policy, climate change and its response to the bushfires this summer.

John Howard and Paul Keating do not seek the spotlight. They do not use social media to attack their successors. They seldom write letters to newspapers. They decline more requests for interviews than they accept, along with invitations to give speeches. They choose their contributions carefully. They have defended their periods in office and occasionally made harsh observations, but they are not dial-a-quote former politicians.

Gillard’s exemplary behaviour as a former PM does not exempt her from critical appraisals of her prime ministership. I always admired her resilience and empathy, kindness towards staff and colleagues, her superior administrative talents, her parliamentary debating and negotiation skills, and her trailblazing status as the first female prime minister. However, I was often a critic of her political strategy and policy decisions. She was a polarising and often unpopular prime minister who lacked authority. This has been well catalogued.

It is also true, as I wrote at the time, that Gillard faced an unremitting campaign from Rudd to wrest back the prime ministership that ultimately succeeded. Those who live by the sword die by the sword, his supporters would say.

Gillard also had to navigate a minority parliament. She dealt with an often hostile press gallery. She faced sexism from some quarters.

Her government can claim achievements such as implementing the National Disability Insurance Scheme, landmark reforms to school education, a major health funding agreement with state governments, an apology to those affected by forced adoptions, and the royal commission into child sex abuse in institutions. She excelled in foreign policy and strengthened relations with the US, China and India.

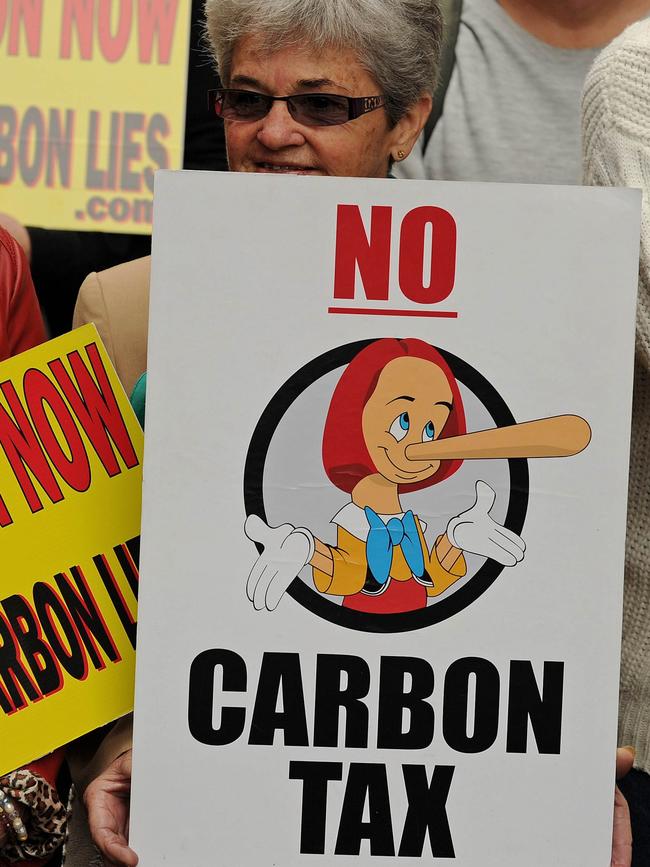

On the other side of the ledger, the carbon price and mining tax did not survive, the budget did not return to surplus, and immigration and asylum-seeker policy was a mess. How Gillard won and lost the prime ministership, and the near electoral defeat in August 2010, will all form part of history’s verdict.

But how people view the past is often revised. We tend to view history through the prism of the present, which reflects changing values and attitudes. New material can come to light. Who precedes and succeeds a prime minister matters. The upshot is that reputations can improve and decline. Yet as memories of issues and events fade, character is seldom forgotten.

Gillard is a fundamentally decent person. This matters. She occupies leadership positions with a range of organisations: chairwoman of the Global Partnership for Education; patron of the Campaign for Female Education; chairwoman of Beyond Blue; and chairwoman of the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership at Kings College in London. She is also a distinguished fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, honorary professor at the University of Adelaide and patron of the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library.

“I meet a lot of people who want to talk to me about my time as prime minister and I’m happy to do that and share what I’ve learned, and I particularly have a lot of young women who want to talk to me about those things,” Gillard says. “But when I came out of the prime ministership I knew I didn’t want to endlessly be a raconteur about what was a limited period of my life. I wanted to be exposed to new people, new thinking and new ideas. And with the organisations that I deal with and things that I do, I get that kind of nourishment.”

It is approaching 10 years since Gillard became prime minister in June 2010. It was the beginning of a decade marked by brutality as four prime ministers were felled by their colleagues. In the five decades before, from 1960 to 2010, only two prime ministers were removed from office by their parties: John Gorton and Bob Hawke. Leadership churn has accelerated. Gillard is the longest serving prime minister since Howard.

The day Gillard vacated the prime ministership, she took a call from Keating. He offered consolation and encouragement. And he tried to put it into perspective. “We all get taken out in a box, love,” he told her. “But there is always tomorrow.”

It was one of several things that prompted sober reflection about how she would distinguish herself in the next phase of her life. “There are precious few prime ministers who go out of office on their own terms,” Gillard acknowledges. “So, if you take it on, then you take it on in the full expectation that it is going to be like that. The important thing is not the fall; the important thing is how you land.”

When Julia Gillard exited the prime ministership in June 2013, she took time to think about what kind of ex-PM she would be. She still wanted to contribute to public policy, drawing on the skills she had gained and the lessons she had learned. She would deploy them for the national, and international, public good. It would be service of another kind.