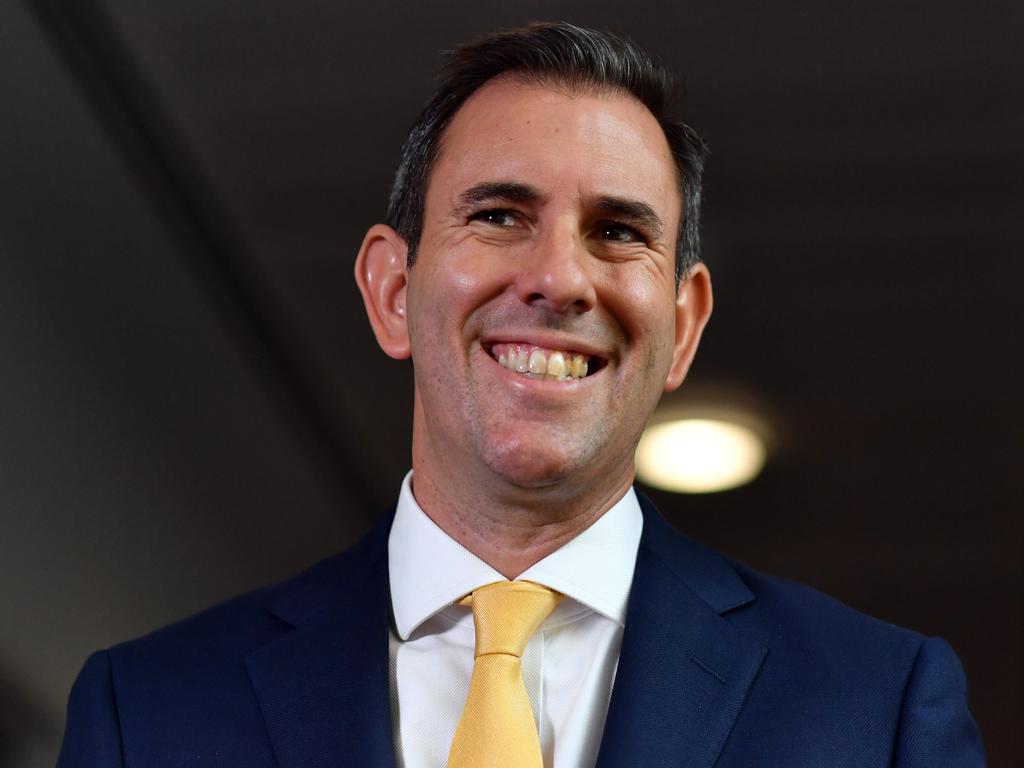

Jim Chalmers: Architect of New Labor has a clear vision for the future

The ALP’s money man Jim Chalmers won’t rest until be becomes treasurer.

It is all part of a rebranded party engaged in barnacle-stripping ahead of an election that will probably be under way in seven or eight months time. It is about Anthony Albanese burying Bill Shorten’s policy and political strategy that crashed and burned at the last election. Labor wants the focus to be on the Coalition this time.

“The Australian people understand that no election is entirely a rerun of the one before and the decisions that we have taken on those tax issues reflect that reality,” Labor’s opposition Treasury spokesman tells Inquirer.

“There are higher priorities for an incoming government in terms of managing the pandemic and building the economy for the future. We are an ambitious opposition and will be an ambitious government.

“You can’t change government policy from opposition. I refuse to spend my entire political career in opposition changing nothing and I think people understand that. We need to better prioritise, focus and sequence our policies, and that is what we are doing.”

The Coalition’s election campaign team is sifting through the many interviews where senior Labor figures advocated and defended the policies that are now for the scrap heap. It is an embarrassment of riches. Just weeks ago, Chalmers was railing against the inequity of the income tax cuts that have already been legislated.

The ranks of Labor’s true believers – the rusted-on party members and supporters, the trade unions, the well-meaning social welfare lobby and the progressive self-righteous think tanks – are not happy. Labor’s policy shift is motivated by political pragmatism rather than policy purity, and for that Albanese and Chalmers make no apology.

“Our supporters are sick of us losing elections,” Chalmers, 43, says. “They understand that we need to be more focused, we need to be more disciplined, we need to have restraint and we need to recognise that many of the problems that we would inherit as an incoming government cannot be solved overnight.

“My message to the true believers is we will be a government in the best traditions of Labor, we will make decisions in the interests of middle Australia, we will be forward-looking and optimistic – and if we get the opportunity, we will be a government the true believers can be proud of.”

It has been a time of soul-searching for Labor since losing the last election. Chalmers was never overly optimistic of Labor’s chances of winning. But the defeat came as a shock for many in the party. It left the party demoralised and contemplating the lessons that had to be learnt.

In June 2019, after stepping from the opposition finance portfolio to the opposition Treasury portfolio, Chalmers recognised the need to rebuild the party’s economic credibility and rejected the politics of envy and class warfare. In his “light on the hill” address a few months later, he argued that Labor had to move back to the centre ground of politics and prize aspiration, opportunity and growth.

“Our policy agenda is all about middle Australia,” Chalmers says. “I take as my guiding light the issues that people talk about around kitchen tables in middle Australia – and that is wages, it is childcare, it is more secure work. These are the issues that are a high priority for us.”

At the last election, Labor did poorly in suburban and regional Australia. Many seats that Labor thought it could win were lost. And many other seats that Labor held came with large swings against the party. Chalmers says he would place the concerns of suburban and regional Australians – which he defines as middle Australia – above others.

“If I become the treasurer, I want it to be in a government of the suburbs by the suburbs and for the suburbs,” he insists.

“Nobody in the opposition spends more time in the boardrooms of Sydney and Melbourne than I do. But if we are to grow the economy strongly, sustainably and inclusively, we need to make our regions and our suburbs a much bigger part of the story.”

So, after the last election, Chalmers hit the road. Over four days, he visited 10 towns in regional Queensland with senator Anthony Chisholm. They clocked about 3000km by road. In this parliamentary term, Chalmers says he has made 39 visits to 21 regional towns in Queensland. They include Cairns, Bundaberg, Mackay, Townsville and Maryborough.

He has studied the fortunes of centre-left parties around the world. He wrote a PhD on Paul Keating. He worked for the party’s national secretariat, and as an adviser to state and federal Labor governments.

He recently sought out Tony Blair, who led British Labour to three election victories and presided over a reforming government, but also blundered by supporting the invasion of Iraq.

Chalmers thinks centre-left parties around the world have things to learn from Blair, and he is right about that. In July last year, Chalmers had a video call with Blair. He logged in to Microsoft Teams from his Logan electorate office wearing a business shirt and tie, while Blair logged in from his home in locked-down London wearing a tracksuit. Blair has long argued that parties of the centre-left must change, or they will die.

What did Blair tell Chalmers? First, to be forward-looking and positive in outlining an agenda that is future-focused. And second, understand and harness the benefits of the tech revolution to build connectivity and fashion policies that deliver a better and more equal society.

In the dead of night last September, Chalmers presented to the Global Progress New Leadership Network, a group of centre-left next-generation leaders, via Zoom. He argued that the GFC exposed flaws in neoliberal economics that contributed to the rise of right-wing populism. He said the answer was not to return to big-state socialism or embrace technocratic centrism.

Instead, Chalmers offered three insights: refocus on jobs and incomes, and do not try to solve every public policy problem quickly; restructure the political contest so it is about competing visions for the future; and redefine risk so that the weaknesses and insecurities of the pre-Covid economy are not seen as solutions for the present.

This has guided his approach to the formulation of economic policy in Australia. But the pandemic has made the task of repositioning Labor especially challenging. Labor has often struggled to find the right balance between keeping the government accountable, critiquing their policies and offering bipartisanship at a time of crisis greater than any other since World War II.

“The government has not got everything wrong, but they certainly have not got everything right,” Chalmers says.

“There have been good ideas badly implemented, and wage subsidies are the best example of that. We said all along the recovery is hostage to vaccines and purpose-built quarantine, so we hope that things get a lot better, but we can’t get ahead of ourselves until those problems are fixed.”

The man who could be Australia’s next treasurer – the sixth in nine years – is thinking about how he would make his mark on the second most important job in government. He would commission a review of the Reserve Bank and its role in monetary and fiscal policy. And he would build up the Treasury’s institutional capacity to improve how it measures and uses economic data.

Chalmers has been impressed with Treasury’s work during the pandemic and he would advise Albanese to keep Steven Kennedy as Treasury secretary if Labor is returned to government.

“Steven Kennedy has served and is serving governments of both political persuasions with distinction,” Chalmers says. “The Treasury has a lot to be proud of over the past few years.”

The recent Intergenerational Report showed Labor would preside over an economy growing slower, with weak wage and productivity growth, and burdened by debt and deficits for the next 40 years. Chalmers argues it would be the worst budget position any treasurer has inherited in the post-war period.

“The virus had a diabolical impact on the economy but if you look at those last national accounts in 2019, we had below-average growth, weak wages growth, weak business investment, and weak productivity – so the economy was remarkably soft going into the pandemic,” he says.

Labor has drawn inspiration from Australia’s post-war experience and proposed a National Reconstruction Fund that will focus on advanced manufacturing, revitalising regions, creating sustainable jobs and lifting wages.

“Australians have a right to expect that we do better rather than just go back to the stagnation that we saw for much of the eight years of this government, even before we had heard of coronavirus,” Chalmers says.

“We need to ensure the economy is stronger, more inclusive, and more sustainable after Covid than it was before Covid.”

Crafting an economic policy agenda during a pandemic and after is difficult enough. And there are plenty of other potential risks to the economy: trade wars, regional security threats, cyber-espionage, and the longer-term impact of climate change.

“One of the things I’m determined to do if I become treasurer is to be prepared for the kinds of uncertainties that we could see,” he says. “I think we were unprepared for the pandemic.”

For now, though, the shaping of a different Labor Party is taking place. Will it be enough? Has Labor really learnt the lessons of its third election defeat in a row? Can it win back the trust of working- and middle-class voters? Will the politics of the pandemic swing back in the Coalition’s favour once the vaccination rates reach 70-80 per cent? Time will tell.

“When parties of the centre left win elections, there are three criteria: when we represent safe change; when our policies and priorities are grounded in people’s real lives in real communities; and when we are optimistic and forward-looking and embrace the future,” Chalmers says.

“So my effort in economic policy is to understand and to reflect those three things.”

Jim Chalmers has a lot of explaining to do. Labor has performed a gold medal-worthy triple backflip from a standing start. The plan to curb negative gearing and capital gains tax deductions has been dumped. Opposition to the stage three income tax cuts has been discarded. And the policy of abolishing franking credits has been kicked to the kerb.