The fifth Intergenerational Report (IGR) released on Monday by Treasurer Josh Frydenberg – looking at the trends in demography, productivity and spending – suggests Australia will stay a caring society but experience a declining social and economic trajectory in its future compared with its past.

The rate of increase in our living standards will fall, perhaps sharply. The anti-reform gridlock in our political system, now more than a decade old with no sign of respite, is going to punish this country and its people on a mammoth scale. That’s obvious from the IGR.

For those who see Australia as a young, growing, dynamic, competitive country, this IGR report should arrive with a thunderclap. In his cautious but frank assessment on Monday Frydenberg recalled Peter Costello telling him last month that IGRs “always deliver sober news”. The Treasurer said the 2021 version “is no exception.”

That’s right. But this report, filled with warning lights, is actually a project in heroic optimism. First, our relative decline is apparent. Real gross national income per person will fall from an average annual rate of 1.8 per cent over the past 40 years to 1.3 per cent over the next 40 years. That’s a sharp decline in our living standards trajectory. People may not notice much year to year, but the lost potential over the decades is huge. It equates to an Australian locked-in underperformance.

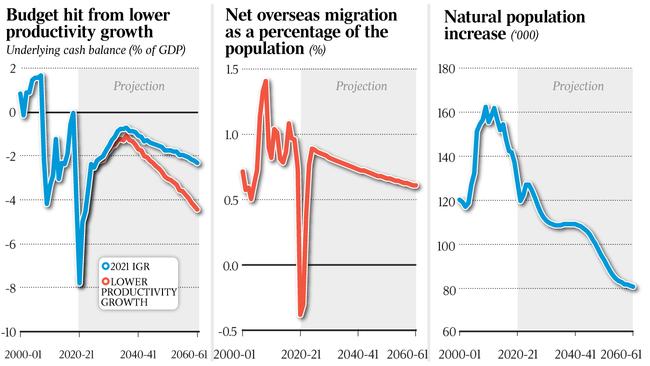

As for the budget, it will be in deficit for the next 40 years. That deficit will be growing in 2060-61 while gross debt is projected to be 40.8 per cent of GDP at this time, and increasing after reaching a low of 36.8 per cent of GDP in 2047-48. This report puts a long-range lens on the real budget outlook looking far beyond the four years of forward estimates.

The fiscal story smashes the Liberal and Labor orthodoxies. The big trends impact like an aircraft carrier that cannot turn easily or quickly – the direction is set. “The message in this IGR is that at some stage we will need a combination of tax increases and spending cuts,” Deloitte Access Economics partner Chris Richardson says. “You will need a combination of both.” The deficit problem is too big for a one-way solution.

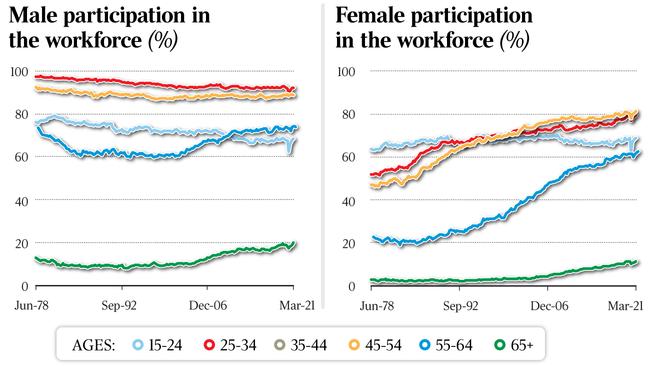

Second, the IGR’s assumption about productivity growth over the next 40 years verges on the untenable. That means its conclusion about living standards verges on the untenable. Yet this is the single most important assumption in the report. It says that labour productivity contributes more than 80 per cent of growth in real gross national income per person – that is, productivity essentially determines our living standards, not population or participation.

Frydenberg acknowledges this. He quotes the famous line from US economist Paul Krugman that productivity “isn’t everything, but in the long run it’s almost everything”. The IGR assumes a productivity growth rate of 1.5 per cent per year because this was the rate in the 30 years to 2018-19.

But there’s a problem – productivity growth over the six years from 2011-12 was only 1.2 per cent and over the past five years was only 0.5 per cent. Slight problem? No, big problem. The report assumes that over the coming decade the productivity rate undergoes “convergence” back to the long-run 1.5 per cent rate. How convenient.

Former Productivity Commission chair Gary Banks in a speech earlier this month warns against this assumption. He doubts whether such productivity levels are “achievable at all under current policy”. If correct, this means future GDP, living standards, deficits and debt levels will all take a much bigger hit than projected by the IGR. Richardson agrees with Banks and brands as “too optimistic” not just the 1.5 per cent rate but the IGR fallback scenario of a 1.2 per cent productivity rate.

“There has been little public acknowledgment of the heightened productivity challenge now facing us and its reform imperatives,” Banks said. Richardson was scathing about the crisis within the political system that has virtually killed off any significant productivity gains.

“Australia did well managing the Covid crisis,” he said. “But you wouldn’t back us in a reform crisis. It’s not governments that run Australia, its oppositions. What we have in politics is supposedly successful oppositions leading to dangerously weak governments.”

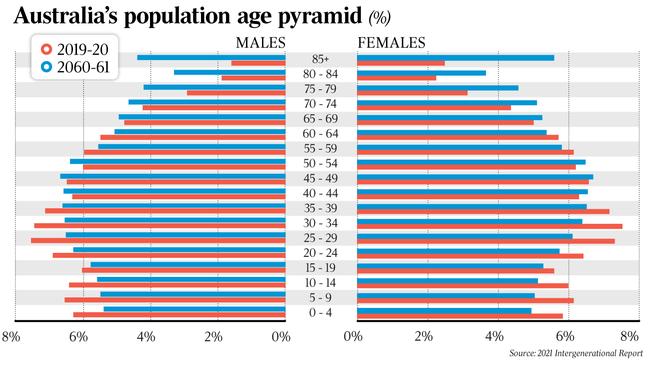

This is an acute summary of Australian politics over the past 15 years. While the government still assumes its tax ceiling of 23.9 per cent of GDP, the spending pressures documented by the IGR will almost certainly bust this ceiling. Spending as a proportion of GDP is projected to rise to a new plateau at 27.7 per cent of GDP at 2060-61, driven by an ageing population and the demands of health, aged care, the NDIS and individual payments.

Real spending per person will nearly double over 40 years to reach $38,680 per person by 2060-61. Spending looms large because the economy will be smaller than otherwise but social spending demands will be larger than ever. Social policy will dictate the budget and create huge difficulties for politicians seeking fiscal restraint.

Health is slated to increase from 4.6 per cent of GDP in 2021-22 to 6.2 per cent in 2060-61 due to rising incomes, population ageing, public hospital demands and medical technology. The report optimistically projects the NDIS to level out at 1.4 per cent of GDP, nearly 30 per cent higher than predicted by the 2015 IGR. The total projected cost of the age pension and superannuation tax concessions will increase from 4.5 per cent of GDP in 2020-21 to 5 per cent of GDP in 2060-61.

National security hawks have their best hopes punctured by the IGR. Defence spending is squeezed by these demographic forces to reach a modest 2.3 per cent of GDP in 2030-31. Anybody backing a radical lift in the defence budget must explain why social spending should be cut or advocate a China-threat tax surcharge.

In his speech, Frydenberg confronted the productivity challenge, saying: “Australia has no alternative other than to pursue economic reform, much of which is hard and contested. It is a national imperative. But the recipe for reforms is unlikely to be the same as in the past.” Too true.

The “big bang” reforms of the 1980s and 90s won’t be repeated. “Reform is likely to be more incremental,” Frydenberg said, listing the government’s current reforms – insolvency laws, superannuation changes, the new personal tax scales and the “patent box” to promote innovation. Scott Morrison and Frydenberg are pragmatists and won’t push reforms that face certain defeat in the parliament.

Australia’s economy will grow at a slower pace over the coming 40 years compared with the past 40 years – an annual 2.6 per cent compared with 3 per cent. Slower population growth is the main factor. We will be an older and smaller nation than previously expected with the ratio of working-age people to those over 65 years falling from 4.0 to 2.7 in the next 40 years.

The IGR is valuable because it assumes current policy but looks at the structural and demographic trends. The real debate the nation needs is about our future economic performance. “The size of the pie is what we should be talking about,” Richardson said. A bigger GDP makes the distribution debate easier to manage. The ultimate message from the report is that Australia shouldn’t be a passive player. It needs a strong, farsighted and activist policy agenda to exceed the outcomes suggested here. But does anybody think the country has the slightest interest in such a wake-up call?

Don’t be fooled by Australia’s startling V-shaped economic recovery. There is another bigger story coming – the grim and mounting long-run trends pointing to a nation of slower economic growth, higher spending, chronic deficits and debt, slower population growth and a political system almost certainly incapable of meeting the national challenge.