Intergenerational Report warns of economic disaster if we don’t act

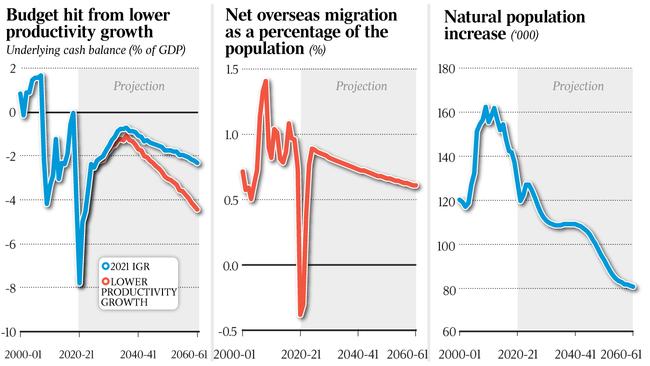

Australians’ average incomes are forecast to be $32,000 lower than projected and the federal deficit twice as large by 2061.

Australians’ average incomes will be $32,000 lower than projected and the federal deficit twice as large by 2061 if the country fails to reverse a decade of slumping productivity growth, the latest Intergenerational Report warns.

Josh Frydenberg has used the report to call on business leaders and all sides of politics to work together and respond to the challenges posed in the IGR.

The Treasurer on Monday said Australia had “received an urgent message: we need to pursue microeconomic reform, and it’s best done when it’s bipartisan”.

But business groups warned that tackling the task of lifting national productivity was impossible when borders were closed, industries were suffering severe labour shortages and the country was being hit by rolling lockdowns.

While consistent with the assumptions in previous IGRs, the challenge of returning to long-run levels of productivity growth has become more acute since 2015, with productivity in 2018-19 slowing to roughly a third of the projected long-run trend.

In a speech to the Committee for Economic Development of Australia on Monday, Mr Frydenberg said boosting productivity was a “national priority” as it was “the most vital ingredient in lifting our long-term living standards”.

“If we want to maintain our living standards, Australia has no alternative but to pursue economic reform,” the Treasurer said.

In the fifth version of a document designed to highlight the country’s long-term fiscal and economic challenges, Treasury assumes labour productivity growth will return to its 30-year average and contribute 1.5 per cent to annual real GDP growth over the coming four decades. Labour productivity growth peaked at 2.4 per cent in the 1990s, but averaged 1.2 per cent over the six years to 2017-18, the IGR shows.

As Mr Frydenberg invited Labor to work with the government in implementing reform, he also said business needed to act to take advantage of new technologies and ways of doing business.

“Reform “is a contested space (and) all industry bodies have a key role to play,” he said.

Deloitte Access Economics partner Chris Richardson warned that a deteriorating political environment had stymied reform and contributed to the recent “woeful” productivity performance.

“Governments don’t determine what happens in Australia – oppositions do,” he said. “Both sides of politics have brilliantly weaponised the politics of whingeing over the past two decades. The end result is that reforms cost too many votes for governments to even try to champion them.”

Innes Willox, chief executive of the Australian Industry Group, said while the pandemic had been costly, “the fact remains that most of the challenges identified in this report predate Covid. Hopefully, the need for action to maintain the Covid recovery will spur governments, businesses and the community more broadly to act more decisively on the numerous issues that have been clear for many years,” Mr Willox, who represents major employers, said.

Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry chief economist Ross Lambie said while there was no “silver bullet” for reform, there was a need for a “sustained commitment to policies across the suite of policy areas … so that the economy has the dynamism, resilience and competitiveness to deliver the sustainable economic growth we need”.

With a more problematic environment for consensus-building, Mr Frydenberg also warned that

the “recipe for reform” was unlikely to be as it was in the past, and that the “big bang” reforms of the previous era – such as reducing trade tariffs and deregulating the financial sector – could not be replicated. “You can’t float the dollar twice. Increasingly, reform is likely to be more incremental – taking each and every opportunity to boost productivity no matter how big or small,” he said.

He pointed to reforms such as the automatic mutual recognition of professional qualifications between states, the recent changes to make the superannuation system more efficient, insolvency reforms, and the funding committed to developing the digital economy.

Committee for Economic Development Australia chief executive Melinda Cilento said the IGR showed Australia could not afford another lost decade of reform.

“Lifting productivity growth … will require sharp policy focus and depend on more Australian businesses performing at or close to world’s best,” Ms Cilento said, noting the country had recorded its worst result in 25 years in a recent world competitiveness report.

Opposition Treasury spokesman Jim Chalmers said “getting productivity growing again in this country is all about cleaner and cheaper energy, and teaching and training our people to keep up with technological change”.

The latest Australian Chamber-Westpac survey of industrial trends – to be released on Tuesday – will show manufacturers struggling to increase production to meet climbing demand as they struggle with the most acute labour shortages since 2007.

The Treasury analysis in the IGR reveals that extending that lower rate of 1.2 per cent over the coming decades, rather than returning to 1.5 per cent as assumed, would have a massive impact on prosperity and the commonwealth’s bottom line. The economy, in real and nominal GDP terms, would be nearly 10 per cent smaller, while gross national income per person would be $32,000 lower than the baseline scenario.

By 2061, the deficit would roughly double – from 2.3 per cent of GDP to 4.5 per cent. Net debt as a percentage of GDP would be 23 points higher at 57 per cent.

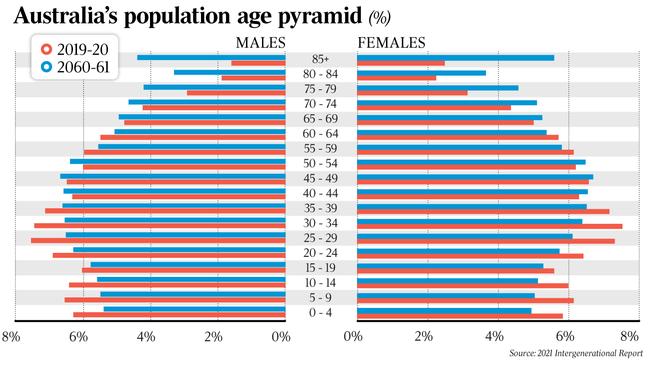

With the IGR revealing that productivity contributed more than 80 per cent of growth in real gross national income per person over the past 30 years, Mr Richardson said living standards depended “much more” on productivity than the other variables identified in the IGR, such as migration and birthrates.

The IGR says there is no single reason for declining productivity, which is a global

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout