There is not a lot in Tuesday’s budget papers that offers durable confidence that Chalmers will end up being right, other than an assumption that lowering energy bills won’t have a secondary inflationary impact.

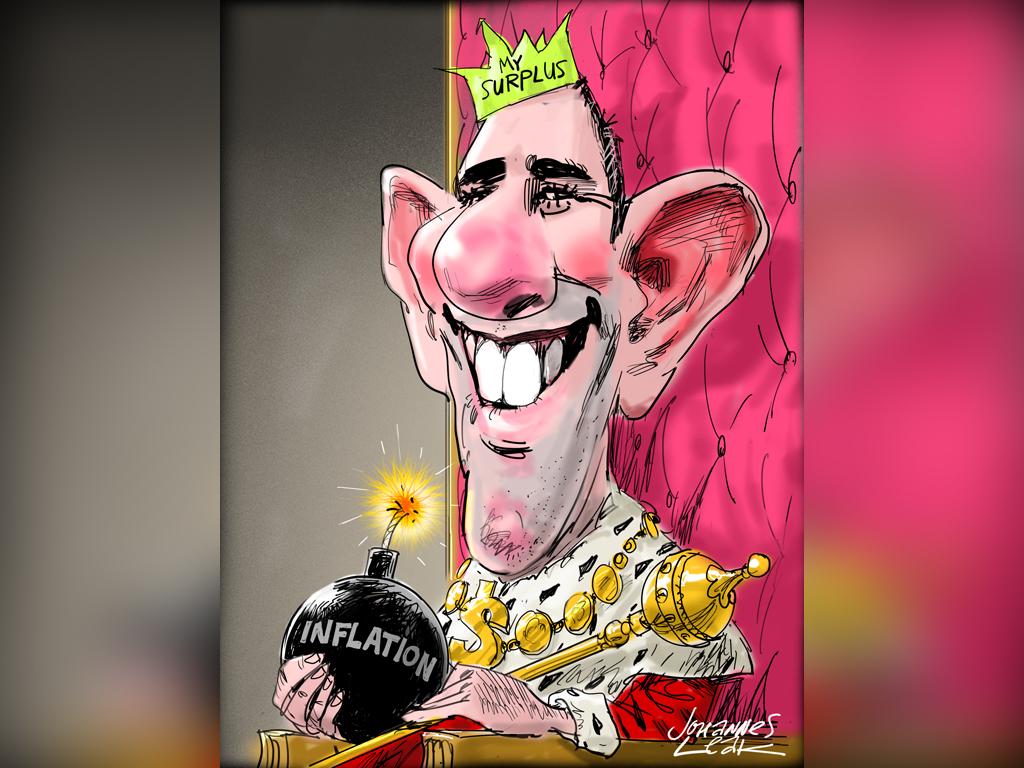

This is a huge political gamble considering the inflation risk as Chalmers seeks to deliver for Labor’s base. While the most vulnerable will welcome the cost-of-living relief, whether borrowers end up having to pay for it in the months ahead will be the key retrospective test of the budget.

In any other budget, Chalmers’ $20bn spending plans might be labelled a stimulus program.

Increases to JobSeeker payments, rent assistance, energy bill subsidies, cheaper medicines, and a boost to wages all have the effect of putting more money into people’s pockets.

The bulk of the spending programs are aimed at those on the lowest incomes and welfare recipients who are generally considered to be those more likely to spend every extra cent they get.

Few would argue such assistance isn’t warranted, giving the budget a moral dimension. But the last thing Chalmers wants to be seen to be doing in this economy with an inflation problem is trying to put out a fire with petrol.

Hence what might otherwise be called stimulus in other times has been rebranded by Treasury as inflation-busting policy.

Chalmers admits that this will be a contested claim.

“In this environment, inflation remains our primary economic challenge … which is why this budget is carefully calibrated to alleviate inflationary pressures, not add to them,” he says.

“Our policies to ease the pressure on households will take three quarters of a percentage point off inflation for 2023-24.”

The foundation for this claim is derived entirely from the energy subsidy, which is paid directly to energy companies to lower bills and the gas and coal price cap which, the Treasury documents say, combined will reduce CPI by 0.75 per cent.

Treasury has argued that the secondary inflationary impact of five million Australian households having in effect more money on the table from cheaper power bills will be less than the reduction in inflation from the policy.

Chalmers will find that many economists might disagree.

They might also argue that increasing JobSeeker payments by $40 a fortnight – which is $10 less than the Morrison government provided during the Covid-19 pandemic – is inherently inflationary as well.

Economist Chris Richardson uses a rough measure that to reduce interest rates by 0.25 per cent, the government would have to take $6bn out of the economy through fiscal measures.

The reverse is also relevant. For every $6bn spent, one could expect the central bank to whack another rate rise on home borrowers.

According to the budget papers, $12bn of the $20bn in spending measures over the next four years will roll out over the next 12 months – suggesting the budget is being frontloaded just at the wrong time.

Treasury counters that only about $4bn of that $12bn relates to the cost-of-living measures, half of which is made up of increased JobSeeker payments and the other half being energy subsidies.

Again, Treasury’s argument is that this will not have a substantial inflationary impact.

But the Treasurer may still have a tough time trying to maintain an argument that this budget won’t bring the RBA back into the picture with more interest rate rises in the coming months.

Chalmers and Albanese have clearly made a calculated decision that if this is the case, it will be a political price worth paying to deliver for Labor’s core constituencies. And it will always have the RBA to blame.

Chalmers’ first full budget has deep parallels to that of his mentor and former boss – the last Labor treasurer, Wayne Swan – before his future budgets were torpedoed by the global financial crisis.

Announcing a $55bn family support package to address the cost-of-living pressures, Swan claimed in his 2008 budget speech that he was delivering a “responsible budget” that strengthened “Australia’s economic foundations” amid international turbulence.

“A budget carefully designed to fight inflation and ensure we meet the uncertainties of the future from a position of strength,” Swan said.

Chalmers’s speech 15 years later is eerily similar in both language and intent, containing the same claim to be a fighting inflation manifesto: “These are the foundations on which our government is building a stronger economy and a fairer society, with greater security in a time of economic uncertainty.”

Jim Chalmers is asking middle Australia to take him at his word that Labor’s first full budget won’t add to the inflation problem and kick mortgage holders in the guts.