Foreigners face tougher security test to invest

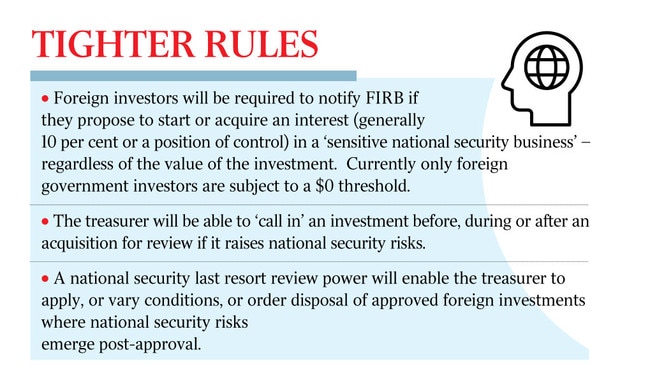

A new national security test will apply to all foreign bids for sensitive assets in the biggest shake-up of takeover laws in 45 years.

A new national security test will apply to all foreign investment bids for sensitive assets, including telecommunications, energy, and technology companies down to small-scale defence suppliers and service providers, in the biggest shake-up of foreign acquisition and takeover laws in 45 years.

The Treasurer will have “last-resort” powers to force assets to be sold or to impose conditions even after a sale is approved if national security is at risk.

The zero-dollar threshold for screening will apply to all foreign investments in any businesses with a national security profile, under the most comprehensive reforms to rules governing the independent Foreign Investment Review Board since it was established in 1975.

Josh Frydenberg said: “Through the introduction of a new national security test, stronger enforcement powers and enhanced compliance obligations, we will ensure that Australia can continue to benefit from foreign investment while safeguarding our national interest.

“The reforms will ensure that our foreign investment regime is able to respond to emerging risks and global developments.”

The clampdown and move to an “enforcement” footing have been driven by the government’s assessment of greater national security risks arising from cyber threats and the deterioration of the global strategic situation.

A government source said there had been a concerning and “significant” increase in investment in critical infrastructure where national security issues had become apparent.

The Northern Territory government’s controversial 2015 decision to approve a 99-year lease of the Port of Darwin to the Chinese-owned Landbridge Group, which has links to the Chinese Communist Party, would not have gone through if these laws had been in place, government sources claimed.

Under the present regime, the Treasurer’s powers when trying to enforce compliance with investment conditions are limited in seeking civil or criminal prosecution of breaches of investment conditions.

The government’s inability to enforce compliance by foreign investors was exposed by the $280m takeover of a Tasmanian dairy farm in 2016 by Chinese businessman Xianfeng Lu when the company failed to meet conditions of the investment approval.

A Chinese bid for Ausgrid in 2016 was also overturned by Scott Morrison as treasurer over a number of national-security concerns raised at the last minute during the sale of the electricity grid by the NSW government.

The proposed legal framework would give the Treasury and Australian Taxation Office powers in line with other corporate regulators to raid offices and ensure compliance by foreign investors.

The ATO would have direct powers of enforcement, which now can only be sought through lengthy court proceedings.

The new laws would apply to any business or asset, regardless of value, including critical infrastructure such as energy and telecommunications but also a second category for smaller businesses involved in the supply of defence services and technology or any business with a “vulnerability”.

National security hawks in government have been pushing for a tightening of the net to prevent a repeat of the Port of Darwin lease to Chinese interests and growing concerns over state and territory government asset sales that could have national security implications.

The new laws would mirror moves by Australian allies in the Five Eyes intelligence network, including the US, UK and Canada, which have all moved to a more defensive posture on foreign investment in critical infrastructure.

The government last month imposed temporary emergency powers that reduced dollar thresholds to zero on all foreign investment in response to concerns that Australian assets were vulnerable to foreign raids during the COVID-19 economic shutdown. The new laws, which have been in the pipeline for 18 months, would make those regulations permanent for investments that raised national security concerns while extending the current zero threshold beyond just foreign government investments to all proposed acquisitions.

To address concerns that the new laws could discourage foreign investment into Australia as the government seeks to revive the economy post-coronavirus, the FIRB process would be streamlined for bids that did not have national security implications. To ensure the flow of foreign capital, entities with less than 20 per cent “passive” ownership from a single foreign government would be excluded from triggering FIRB approval.

Other broader exemptions from FIRB approval would also be expanded.

While the new investment framework would be applied through an “indiscriminate” policy applying to all source countries, it comes at a time of turbulent relations between Canberra and Beijing over China’s trade retaliations after Australia’s push for the global inquiry into the coronavirus and controversy surrounding the Victorian government’s Belt and Road contract.

While the US is still the largest source of foreign investment in Australia, followed by Canada, Singapore and Japan, China has emerged as the biggest investor year on year over the past five years and is ranked fifth with $13bn of investments in 2018-19.

Government sources said the laws as they stood had “huge gaps” which allowed foreign bidders to get around FIRB approval on investments under $275m or less than $1.2bn for countries that had free trade agreements with Australia. There has been increasing concern that many investments with national security implications were not being “picked up”.

“The Morrison government’s reforms to Australia’s foreign investment regime represent the most significant changes since its introduction in 1975,” the Treasurer said.

“It is vital that the government have the ability to ‘call in’ an investment before, during or after acquisition for review if it raises national security concerns. Australia has an enviable track record when it comes to welcoming foreign investment from around the world. These reforms will not change that.”

FIRB chairman David Irvine, who has also served as ASIO chief and ambassador to China, backed the changes.

“This is a significant package of reforms that will put Australia’s foreign investment review framework on a stronger and more sustainable footing,” Mr Irvine said.

“The package appropriately addresses increasing risks to the national interest whilst ensuring Australia remains welcoming and open to foreign investment.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout