Coronavirus: Universities graduating from pandemic with a heck of debt

Ratings agencies and economists warn that the cost of debt was increasing for the higher education sector as the pandemic halted the lucrative international student market.

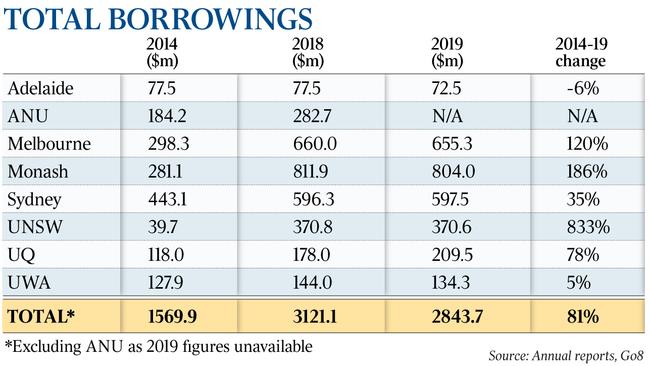

The nation’s most prestigious universities have binged on debt in the lead-up to the coronavirus crisis, almost doubling their level of borrowings in the past five years to $2.8bn in a building spree to cater for international students and replace ageing infrastructure.

Ratings agencies and economists are warning that the cost of debt was increasing for the sector as the COVID-19 pandemic halted the lucrative international student market and left smaller institutions struggling to slash costs.

Monash University has the highest level of debt of the Group of Eight institutions, with borrowings surging from $281m in 2014 to $804m last year, according to its annual report released on Tuesday. The University of NSW has also recorded a rapid increase in borrowings, from $39m in 2014 to $371m.

The University of Queensland, according to its annual report, has borrowed $91m more in that period, taking its total borrowings to $209m.

Last year, it arranged a $251m loan facility with the Queensland Treasury Corporation as it launched an aggressive building program that included buying a Brisbane CBD building known as The Chambers. The university organised a separate $87.1m QTC loan for a solar farm in Warwick.

Group of Eight chief executive Vicki Thomson said the increased debt was used to upgrade “decaying” infrastructure.

“Our universities do not have the flexibility to raise capital, as is typically undertaken by the corporate sector,” she said.

“Our universities have only relatively recently begun to borrow, largely to fund increased capital requirements to ensure we don’t have decaying infrastructure … to have the best educational facilities for our 400,000 students and to ensure our research capacity, which in and of itself is a contributor to the economy.”

Joyce Yu, a Commonwealth Bank credit analyst, said investors were pricing in “higher risk for default for university debt” compared with banks and governments. “The cost of borrowing for universities compared to the bank bill swap rate, which measures the rate at which prime banks can lend to each other, has increased by 50 basis points to 60bp in the last two months,” she said.

“But absolute funding costs for the unis are little changed if not lower, given swap rates are much lower now than where they were before the COVID crisis.”

Macquarie University issued a $150m, 20-year bond last month with an interest rate of 3.05 per cent, three times the rate paid by the CBA for its borrowings.

The debt figures emerge amid a standoff between Education Minister Dan Tehan and the universities, which have been excluded from the JobKeeper wage subsidy, over extra funding as the pandemic takes it toll.

Universities Australia forecasts the sector will lose up to $16bn over the next three years because of a lack of international students, impacting on staff and research.

Late last month, ratings agency S&P shifted its outlook for Australian universities, which are largely rated AA or AA+, to “negative”, citing a deeper recession in 2020 and increased uncertainty surrounding the return of international students after the pandemic eases.

“If one of the universities were to end up in financial stress, we assume the government would step in to bail them out,” said Anthony Walker, an analyst at S&P. “The Australian universities have increased their debt at a faster rate than their UK and Canadian peers but they are still relatively lowly geared.”

La Trobe University, which is not part of the Group of Eight, denied on Thursday that it was going broke, after it approached the major banks for a new debt facility.

“The university is in productive and ongoing discussions with its three banks for increased facilities that we believe will meet our funding requirements in the short term,” La Trobe vice-chancellor John Dewar said.

Ms Thomson said that the universities had “undertaken the borrowing from a position of strong management”.

“That is not to say that COVID-19 does not present real financial challenges — it does, and will continue to do so,” she said.

The University of Sydney, one of the largest in the country, has $597m in borrowings, according to financial information published at the end of last month. A spokeswoman said it still had $300m in undrawn lines of credit.

“One of our priorities has been to create a place where our students can thrive and our researchers have the facilities they need to do their critical work — that’s why over the last six years we have invested more than $1.6bn on a major capital works program,” she said.

The university has put on hold building upgrades worth $35m a year, and a new construction worth $22m.

“All future capital works are also on hold,” she said.

A University of Queensland spokeswoman said a planned health and recreation centre project had been postponed.

However, she said, the student accommodation project had begun last year “to provide competitively priced on-campus accommodation, including those from rural and remote areas”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout