Federal budget 2023: History shows the road to surplus heaven is paved with good interventions

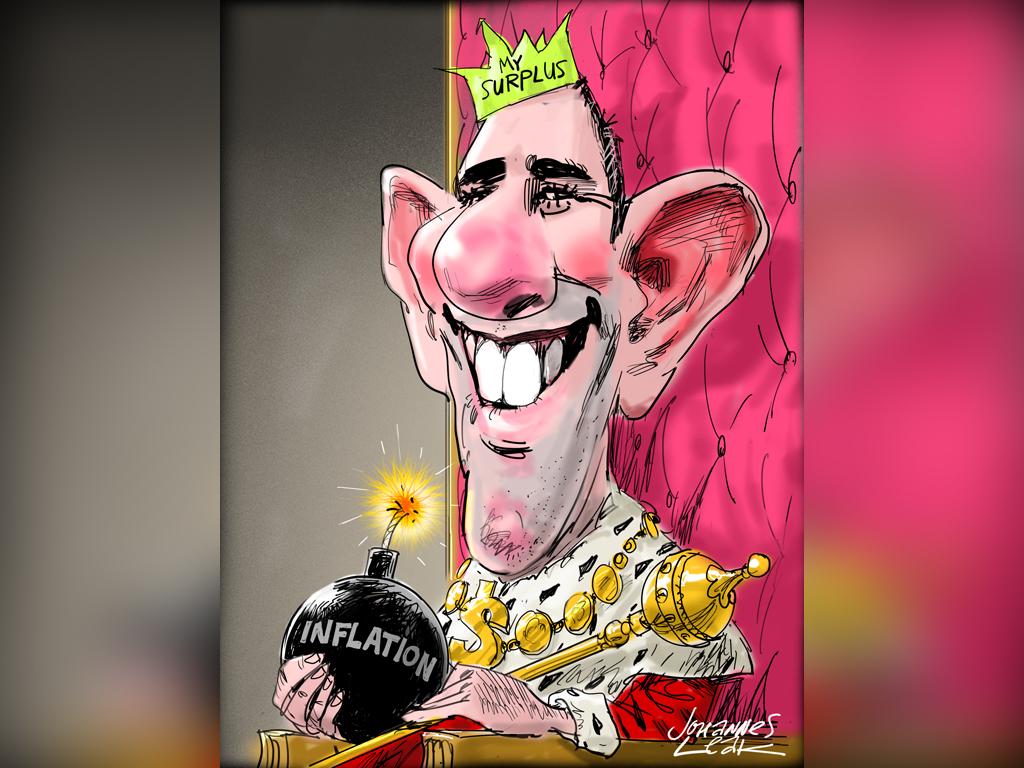

Jim Chalmers, hit by a revenue rainbow, is one of the lucky few.

When debt gets away from custodians and the budget carries flab, consolidation is the cure. Otherwise the road to ruin is fast and downhill.

We’re now at a critical point. The past offers a road map.

When Paul Keating became treasurer in 1983, Australia was coming out of recession and drought and the budget was in an awful mess. The then-Treasury secretary’s advice was blunt: “The magnitude of the fiscal imbalance is unprecedented in Australia during peacetime, as is the level of government spending.”

The way back would be slow, with the Hawke government navigating a dollar devaluation, a current account crisis and entrenched high unemployment. Bold election promises were immediately dumped. In 1986, Keating detonated the “Banana republic” truth bomb, as the world closed in on us and the currency was in free fall.

Labor hacked away at spending, tightened means testing for welfare, kept up its deregulation program and reformed the tax system. Eventually, through the muscular austerity of former finance minister Peter Walsh, the budget returned to surplus in 1987-88, and stayed there until the Reserve Bank ended the 80s debt-and-spending binge with its brutal monetary assault. Another deep recession battered the budget.

John Howard won the 1996 election on a “relaxed and comfortable” vibe, promising tax cuts and no new imposts. Fiscal reality quickly set in, with a hefty deficit amid falling revenue in an economy doing well. Treasurer Peter Costello’s first budget included swingeing spending cuts – including to tertiary education and the ABC – and a few billion in new taxes. Funds from Telstra’s partial privatisation would go to reducing debt and borrowing costs.

Costello introduced a new charter of budget honesty, moved the annual fiscal pageant to May, and in his second outing he boldly claimed a return to surplus for 1998-99. A strong economy helped the Coalition achieve that a year ahead of schedule.

The GST was introduced in 2000 and personal income taxes were cut. Strong growth and a mining boom that swelled Canberra’s coffers kept the budget in rude health, even as Howard splashed the proceeds back to key voter groups in tax cuts and social services spending.

“Kevin07” Rudd ended Howard’s almost dozen years in office. Labor inherited an underlying cash surplus of almost $20bn (akin to double that in today’s dollars).

Wayne Swan’s first budget in May 2008 was a nation-building extravaganza, with new funds for infrastructure and health expansion, and another it inherited for education. But the global financial crisis later that year saw the government following the then-Treasury chief’s advice to “go hard, go early and go households” in its fiscal stimulus responses to keep the economy afloat and unclog financial arteries.

The turnaround in the bottom line was swift, as social support and public works spending soared and revenue plummeted. In his 2009 budget speech, Swan could not bring himself to utter the word “deficit”. The former treasurer kept a light on the porch for a return to surplus, plotting and planning, tweaking and trimming, as cheery rhetoric parted with harsh reality.

This reached its forlorn climax in May 2012, when the former deputy prime minister said in his budget speech: “The four years of surpluses I announce tonight are a powerful endorsement of the strength of our economy, resilience of our people, and success of our policies.”

A little over a year later, Julia Gillard was cut down by Kevin 2.0, who promptly lost an election to Tony Abbott.

The new government had said the transition would be pain-free, with no cuts to key programs, although there was a hint from the incoming custodian that the “age of entitlement is over”.

A commission of audit reported on unsustainable trends in spending, as the deficit bulged out to 3 per cent of the economy.

The tough medicine in Joe Hockey’s 2014 budget seemed to voters to come out of nowhere and the political backlash to proposed spending cuts and co-payments for GP visits stunned the Coalition. It would take years of steady cost control by former finance minister Mathias Cormann to get the budget back into balance, if not quite “back in black” as Josh Frydenberg boasted ahead of the 2019 election.

Of course, bracket creep – when wage inflation causes workers to pay an increasing proportion of their income in tax, even though tax settings may not have changed – figures in this fiscal redemption story. It’s the lazy way to budget repair and mucks up the tax system

“Bracket creep has played an important role in fiscal consolidation after major downturns in the past,” the Parliamentary Budget Office says.

“For example, both the average tax rate and total tax revenue as a percentage of GDP were relatively low after the 1990s recession and the global financial crisis, but bracket creep allowed both measures to gradually increase, improving the budget position.”

Scott Morrison declared war on this “thief in the night” in 2018, setting off a three-stage process of tax relief to return excess revenue. The pandemic changed everything – except some of the tax cuts were juiced up and government spending hit a record 31.6 per cent of GDP at the height of the Covid-19 health and economic emergency response.

But ageing of the population, a growing debt bill, a new security environment, the spread of big government and a sub-optimal tax system have combined to put the budget in structural deficit for the coming decade and beyond. The sugar hits of high commodity prices are not a solution.

Just after last year’s election, Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy reminded the political class and voters that given the nation faces an economic downturn roughly every 10 years, “Australia needs to rebuild fiscal buffers to ensure the government can respond effectively to future crises”. When the economy grows faster than interest payments, the debt burden decreases. But over our history, Kennedy said budget surpluses had played the key role in reducing debt, with “favourable growth and interest rate dynamics assisting or being neutral”.

“The current projected reduction in debt to GDP is unusual in that it is relying solely on favourable growth and interest rate dynamics to reduce the ratio,” he told a gathering of economists.

“A more prudent course would be for the budget to assist more over time. This would especially be the case if growth and interest rate dynamics become less favourable over time.”

That’s where we’re at right now: spectacular good fortune for a brief moment and a burst of revenue for Canberra. But rusted-on spending commitments that will keep growing for decades means there’s a chronic burden on young workers and those still at school.

Lucky Jim, in his second budget, has stumbled into surplus. But with “loose as a goose” rules, and little effort to contain spending, the Treasurer is taking only baby steps on the path to fiscal repair.

It’s a leap of faith, rather than a coherent strategy. An unorthodox way to get to budget heaven.

Some treasurers get lucky on the hunt for a surplus. Others are lazy and lean on bracket creep. One or two become so obsessed with the white whale of budgeting, they lose their political mind.