Bob Hawke obituary: farewell the people’s prime minister

There has never been a politician like Bob Hawke. His rise was powered by a sense of destiny.

Labor prime minister 1983-91. ACTU president 1970-80. Born Bordertown, South Australia, December 9, 1929. Died Sydney, New South Wales, May 16, 2019, aged 89.

There has never been a politician like Bob Hawke. His rise to the prime ministership was powered by a sense of destiny, personal ambition and his determination to turn the country in a new direction. His tools were consensus leadership, a belief that ignorance was the enemy of good policy and a unique bond with Australians.

No prime minister has been more popular — his approval rating reached 75 per cent in 1984 — and he sustained above average ratings for most of his almost nine years in government. He is Labor’s longest-serving prime minister, and the third longest overall, and he led the party to an unmatched four election victories in a row.

The Hawke government fundamentally changed the economic, social and environmental policy settings of Australia.

The economic reforms were groundbreaking: the float of the dollar, deregulating the financial system, slashing tariffs, introducing universal superannuation, overhauling the tax system with big reductions in company and personal tax rates, and privatising assets. These changes laid the basis for three decades of economic growth. The budget was structurally repaired, and spending cut in real terms, which produced four surpluses — the first since the 1950s. An Accord with unions moderated wage claims in return for social wage benefits.

The social policies were also transformative. The reintroduction universal health care — Medicare — is now sacrosanct. Welfare spending was better targeted and those Australians in the lowest socio-economic cohorts saw living standards improve. School retention rates more than doubled. The university and college sectors rapidly expanded.

Hawke was particularly proud of his government’s environmental achievements, which included establishing Landcare, stopping the Franklin Dam in Tasmania, saving the Daintree in Queensland and prohibiting mining in Antarctica. These green credentials paid an electoral dividend in 1987 and 1990 with vital preference votes from minor parties.

He wanted Australia to be a creative middle power punching above its weight on the world stage. He forged good relations with Ronald Reagan and George Bush — having no truck with anti-American sentiment that still existed within some sections of the Labor Party — and strengthened the ANZUS alliance. He enthusiastically supported the First Gulf War (1990-91) and sent military forces.

Hawke was one of the last Cold War leaders. He used the Commonwealth to press South Africa to abolish apartheid, often infuriating Margaret Thatcher, and advocated for Nelson Mandela’s release from jail. He met Mikhail Gorbachev in Russia. Having made the Asia-Pacific a focus of his foreign policy, he personally led the establishment of the APEC multilateral trade forum. He was an enthusiast for the “opening up” of China and publicly wept after the Tiananmen Square massacre.

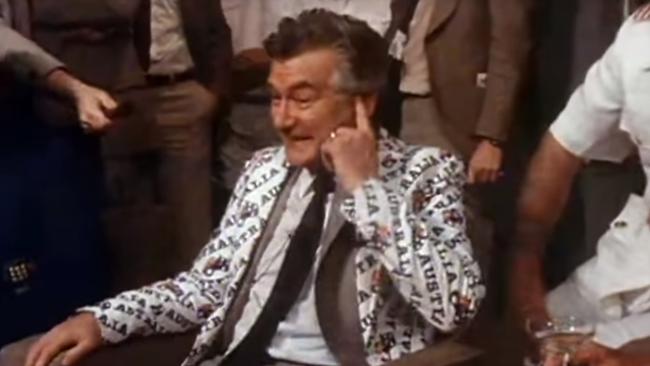

Hawke embodied a mix contradictions and contrasts, but he was an authentic political leader. While ACTU president (1970-80), he gained a reputation for being a drinker and a womaniser — traits that would disqualify any budding politician today. His emotions, whether revealed by tears or a temper, were often in technicolor display. But he never hid who he was or tried to be something that he was not.

He was a larrikin, down-to-earth, sports-loving union leader and prime minister who was also an Oxford Rhodes Scholar with a commanding intellect. He aroused strong feelings in the 1970s — some Australians loathed him while others saw him as a political messiah. He gave up the booze and moderated his behaviour to become prime minister.

Hawke’s rise to power took place outside the political system. He was appointed the ACTU’s research officer and advocate in 1958, and within a few years enjoyed a national profile. But it was not until 1980 that he was elected to parliament. Just over two years later he was Labor leader and then prime minister. Although he had been Labor’s national president (1973-78), he was seen as somewhat above politics.

Earning respect for his ability to resolve industrial disputes in the 1970s, Hawke made conciliation the centrepiece of his pitch for the prime ministership. He wanted to heal the divisions that marked Malcolm Fraser’s Coalition government (1975-83). Hawke’s vision for Australia was a more competitive economy and compassionate society at home, and be an independent and respected nation abroad.

The Hawke government (1983-91) was more pragmatic than ideological and many of its policies were crafted by necessity rather than design. But seared into Hawke’s mind was Singapore prime minister Lee Kuan Yew’s admonition that Australia would be the “poor white trash of Asia” if it did not change its economy and society.

As longstanding policy pillars tumbled, and Labor agonised over the slaying of sacred cows such as privatisation and tariff cuts, it was rarely smooth sailing. Cabinet and party disputes were frequent but Hawke managed to steer Labor to victory after victory at the polls. He placed a premium on political persuasion, whether by logic, reason or passion.

Hawke was able to skilfully lead a party and a government through period of profound change at home and abroad while retaining the support of voters. But in 1991, he became the first Labor prime minister to be felled by his party room.

A recession, partly caused by misreading an overheating economy, had taken the shine well and truly off Hawke. His ambitious deputy, Treasurer Paul Keating, had long eyed the party leadership. A majority of voters wanted him to continue but a majority of his colleagues felt he could not win another election, and he lost a party room ballot and therefore the prime ministership.

* * *

Robert James Lee Hawke was born in the small country town of Bordertown, South Australia, on December 9, 1929. His father, Clem, was a congregational minister. His mother, Ellie, was a schoolteacher.

His older brother, Neil, was at boarding school during much of Hawke’s youth. Neil contracted meningitis at a local swimming pool and died in 1939. This had the effect of intensifying Clem and Ellie’s love for young Robert.

In 1935, the family moved to Maitland on the Yorke Peninsular. Hawke was often sick as a child and his mother thought a high-fibre diet would help. This gave Hawke a distinctive thick curly mane of hair that remained full until his death.

Ellie was a prominent member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and enlisted Robert into its youth wing, the Band of Hope. He broke his mother’s heart when he took a strong liking to the amber ale after tasting it for the first time when at a University of Western Australia law faculty dinner in 1949.

Hawke’s political ascendancy was, he was told, a matter of destiny. While he had spoken of being a farmer or doctor as a child, Ellie believed her son would lead the nation one day. Hawke was showered with love by both parents and made to believe that he was special.

While he did not see the divine hand of God in his journey from Bordertown to The Lodge, he did feel that he was being favoured with some kind of “guidance”. When a motorcycle accident nearly killed him at age 17, he felt his life had been spared for a reason and he was going to make the most of it. This was a turning point.

After graduating from Perth Modern, Hawke joined the Labor Party in 1947 while studying at the University of Western Australia. Albert Hawke, his uncle, later became premier (1953-59) and was particularly influential. He won election as president of the Student Representative Council. He graduated with law and arts degrees.

Hawke was also deeply religious in these years and joined the Congregational Youth Fellowship. But he lost the faith on a student trip to India in 1952 where he witnessed widespread poverty.

He immensely enjoyed his time at Oxford on a Rhodes scholarship (1953-55), where he gained a Bachelor of Letters for writing a thesis on wage fixation. While there, Hawke broke a record for drinking a tankard of beer (2½ pints) in 11 seconds, a feat that he said endeared him to the Australian people as much as anything else he ever achieved.

After Oxford, Hawke spent two years at the Australian National University working on a PhD and teaching. He also began assisting the ACTU with wage cases and secured a full-time position in 1958. His victory for the unions in the basic wage case in 1959 earned him public admiration and his star began to rise.

He won a ballot for the ACTU presidency in 1969, defeating Harold Souter by 399 to 350 votes, with the support of left-wing unions. He joined Labor’s federal executive in 1971, gained a seat on the International Labour Organisation’s Governing Body in 1972 and was appointed to the Reserve Bank Board in 1973.

No other person has been talked about as a future prime minister more than Hawke. The idea was being written about in the 1960s. But the full gamut of Hawke’s emotions — tears and temper — were so often on display that journalists frequently wrote that he had “blown it”. Yet, he always recovered and another wave of “when will Hawke go to Canberra” stories would come around.

In 1963, Hawke stood as the Labor candidate for the Victorian seat of Corio and lost to the Liberal’s Hubert Opperman, a former Olympic cyclist. “That was the best thing that ever happened to me,” Hawke later recalled. While Labor remained in opposition, Hawke’s star continued to rise in the industrial and political labour movement. He was made a Companion of the Order of Australia in 1979.

After the 1975 election drubbing, Gough Whitlam urged Hawke to come into the parliament and immediately lead the party. The plan leaked, and although Hawke was lukewarm on the idea, it was in any event killed. “It was a chalice that I was quite happy to see pass by,” Hawke reflected.

Hawke eventually took the plunge and won the Victorian seat of Wills in 1980. But he was reluctant to give up the ACTU presidency, then often described as “the second most important job in Australia”. He began stalking Bill Hayden’s leadership of the Labor Party in earnest.

But he knew he had to change. Hawke identified with John Curtin, who had overcome his own inner demons to lead the nation during wartime. “We had in common that we both used to drink too much and gave it up,” he said. Still, Hawke’s parliamentary colleagues were not all persuaded that his talents outweighed his flaws, and he lost a leadership challenge in 1982.

Hawke, like Hayden and Keating, had learned lessons from the Whitlam government, which tried to do too much too soon and was often plagued by division and dysfunction. Whitlam, though, was not always helped by Hawke, who repeatedly clashed with the government as ACTU leader. Hayden helped restore Labor’s policy credibility, recruited new candidates and remade the front bench.

In early 1983, Hayden was persuaded to make way for Hawke. “It wasn’t as though he’d done a bad job, but the question was very debatable as to whether he could win the election,” Hawke recalled. Hayden’s resentment lingered but he had a good relationship with Hawke as foreign minister, and appreciated his later appointment as governor-general.

Fraser called an election on the same day that Labor swapped Hayden for Hawke. The new Labor leader promised to “bring Australians together” with consensus-style leadership. Labor won a 25-seat majority in March 1983 — it’s greatest electoral triumph since Curtin’s election win in 1943.

Hawke fit into the prime ministership with ease. He maintained his larrikin style but was more “presidential” than any other, and the government traded on Hawke’s standing with voters. Occasional flashes of vanity and arrogance, or tears over his daughter’s drug addiction in 1984, never seemed to do lasting damage.

Ministers remember Hawke as a good chair of cabinet. He let ministers do their job while he worked hard to stay across cabinet business. He gave the government overall direction and insisted on unity and discipline. He managed caucus well, aided by faction leaders, and insisted upon frank advice from his staff and public servants.

Hawke was supremely confident but secure enough in himself that he could share power. The critical partnership was with Keating as Treasurer. There was a rivalry between them, which later spectacularly exploded, but there was also affection for one another.

Keating often provided the locomotive drive to the Hawke government. Their styles — Hawke more collegiate, Keating more combative — complemented each other. They were almost always united on policy and political strategy.

Keating, however, grew impatient with Hawke who in 1988 had promised to hand over the leadership of the party after the 1990 election. When Hawke reneged, Keating was determined to blast Hawke out of office. A leadership challenge in June 1991 failed but a second narrowly succeeded in December 1991.

The bond between Hawke and Keating, which sometimes fractured when they were both out of office as they battled for their respective places in history, was repaired in recent years and remained strong until the end.

Although he was named Father of the Year in 1971, Hawke recognised that Hazel Hawke was both mother and father. She stood by him, even when he continued his philandering before, during and after the prime ministership. They married in 1956 in Perth and had four children: Susan (1957), Stephen (1959), Rosslyn (1960) and Robert (1963) who died after being born premature. The dissolution of their marriage in 1995 hurt Hazel deeply. But he always respected Hazel, and was with her when she died in 2013.

Hawke had numerous affairs, the most prominent with journalist Blanche d’Alpuget. She wrote a tell-all biography of Hawke that was published in 1982 and they married in 1995.

They had first met in Jakarta, Indonesia, in 1970 and were both married at the time. Hawke promised to divorce Hazel and marry Blanche in 1978, but later backed out when he thought it might damage his political career. The affair was renewed in the mid-1980s. Hawke, who openly admitted his infidelity, said Blanche gave him the happiest years of his life.

* * *

There were three areas of achievement that Hawke most wanted to be remembered for.

First, he nominated the National Economic Summit in 1983 that provided the springboard for the major economic reforms of that decade. Second, he named school and higher education changes which provided greater equality of opportunity. Third, he identified his role in ending apartheid in South Africa. Hawke had been one of the leaders for racial equality in South Africa since the 1970s. As prime minister, he worked with other Commonwealth leaders to implement trade and investment sanctions.

Hawke acknowledged that his government misread the economy in the late 1980s and apologised for the recession in 1990-91. His other major regret was not doing more to advance land rights for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. He blamed Brian Burke, the West Australian Labor premier, who warned of an electoral backlash.

During Hawke’s final press conference as prime minister, he said that he wanted to be remembered as a “dinky-di Australian” who “loved his country” and “loves Australians”. Hawke believed that his bond with Australians was what sustained him in public life, motivated him to try to change the economy and society, and gave him faith in the essential decency of the people who lived in the greatest country on earth.

This is the key to understanding Hawke’s life. His “special relationship” often attracted sneers from colleagues and opponents, but it was inexorably linked with who Hawke was as a person and political figure. No other politician has come close to emulating this mutual affection, which transcends generations, and was the bedrock of his success.

“The genuine love and respect I had for the Australian people was warmly reciprocated,” Hawke said in a previously unpublished interview. “I think this is the basic point: that with a lot of politicians they look at them and say, ‘They’re just using us. but Hawkey really is one of us’.”

Hawke is survived by his second wife, Blanche, his daughters Susan and Rosslyn, and his son, Stephen.

Troy Bramston is writing a biography of Bob Hawke that will be published by Penguin Random House.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout