Balancing restraint, help: Jim Chalmers details what to expect from 2023 federal budget

Hard decisions made, Jim Chalmers flags increased support payments targeted to the vulnerable, with forecasts to show a ‘substantial slowing in the economy’ but not a recession.

“Budgets are a series of hard decisions and some of these hard decisions had been neglected for too long,” Jim Chalmers tells Inquirer in an exclusive interview.

“We had to find room to fund programs that didn’t have ongoing funding. We had to find room to make a big investment in our national security at the same time as we provide cost-of-living relief, and do all of the other things that we need to do to lay the foundations for growth.”

When the printers started rolling on the budget papers on Friday night, the Treasurer admitted to feeling “mostly relief”. The decisions have been made. The figures have been finalised. And now, over the weekend, he will turn his mind to finalising the speech before it goes to print on Sunday night.

The 2023-24 budget to be delivered next Tuesday night is Chalmers’ second (the first was last October) but it is his first full financial year blueprint. Speaking in his Parliament House office, where he has spent most days in recent months, he says there were “more good ideas than we could fund” but emphasises that it is only one building block in the government’s economic strategy.

“Budgets aren’t moments in time, they are staging points for progress,” he says.

“October was about bedding down our commitments and aligning the budget with economic conditions. May will be about cost-of-living relief and setting us up for the future … there will be another budget next May for us to build on what I think is already a substantial amount of progress.”

Chalmers inherited a budget deep in the red with a structural deficit of about $50bn, and federal government debt forecast to surpass $1 trillion. He has had to deal with a cost-of-living and inflation crisis as mortgage interest rates and rents rise rapidly. And there are huge demands on future expenditure with AUKUS and the Defence Strategic Review, and the runaway cost of the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

While the Reserve Bank is focused on the demand side of the economy, trying to slow consumption by lifting interest rates, the government is focused on the supply side by investing in advanced manufacturing with the National Reconstruction Fund and boosting workplace participation by improving access to and affordability of childcare.

Chalmers believes fiscal and monetary policy are aligned. “Our job is to try and find as much room as we can to help people through a difficult period but also show sufficient restraint so that we are not making the job of the Reserve Bank that much harder,” he says. “So that’s the difficult balance that we are trying to strike. We will be able to provide some cost-of-living relief in a way that doesn’t add substantially to inflation.”

There have been calls from Labor backbenchers and the crossbench to increase the rate of JobSeeker, boost rent assistance and reintroduce the parenting payment for single women with children over age eight.

Chalmers flags increased support payments that go beyond energy bills, lower childcare costs and cheaper medicines, but it will be targeted to the vulnerable.

The budget forecasts will show a “substantial slowing in the economy” but not a recession. This is a consequence of interest rate rises and a weaker global outlook, and Chalmers acknowledges it will have implications for unemployment, which is currently at the low level of 3.5 per cent. He is optimistic about the economy, though, given inflation has peaked, wages are growing and the high commodity prices for exports.

No treasurer has delivered a surplus budget since Peter Costello in 2007-08. Understandably coy about the bottom line, Chalmers says the repair work will continue. Much of the upward revisions to revenue will be used to pay down the deficit and debt. “There will be a decent improvement this year and a bit of an improvement next year,” he says. “But our pressures in the budget are intensifying rather than easing.”

Anthony Albanese and Chalmers were born on the same day but 15 years apart (Chalmers is 45). They are different generations, come from different states and backgrounds, but see the economic and budget challenges through the same lens. The Treasurer sits directly opposite the Prime Minister in cabinet meetings, and alongside Finance Minister Katy Gallagher and Leader of the House Tony Burke.

“We don’t have an exactly identical view about everything but our values and our approach to some of these key challenges are very similar,” Chalmers says. “When he says that he wants to let ministers do their jobs, he means it … I try to use the cabinet to give people a sense of where the economy’s headed, where our agenda is headed, and to try and brief them broadly and frequently.”

The Treasurer says he has established effective relationships with Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy and Reserve Bank of Australia governor Philip Lowe but is making reforms to the institutions they both run, along with a renovation of the Productivity Commission, to ensure they remain “world’s best practice”.

He wants Treasury to measure wellbeing and improve the implementation and evaluation of policies. The Reserve Bank board is being split into two – one focused on governance and another on setting interest rates – in the biggest overhaul in decades. The latest Productivity Commission five-year report revealed productivity growth has averaged just 1.1 per cent a year, and Chalmers is overseeing a change in its “structure and remit” for the future.

“I want to leave behind institutions that are stronger than I found them,” he says.

“It’s a real obsession of mine because if you want to rebuild trust in politics and you want to strengthen the economy, you’ve got to strengthen the institutions that are central to both of those things.

“If we want to grow our economy in the next generation, it will be determined by how we manage technology, how we manage the shift to the care economy and how we get this energy transformation right. So, in order to do that, you need your best people, the strongest possible institutions and the most considered policies.”

On the eve of the federal election last year, The Weekend Australian revealed that an Albanese government would release a new Intergenerational Report every term rather than every five years, with the first in the second half of 2023. Chalmers confirms that timeline.

“I want to play the long game here,” he says. “I want to help people in the here and now, but I also want to set the country up for the future, and to do that we need to build the best, most robust understanding of where the place is headed and how we take maximum advantage of those trends and transitions in our economy and in our society. The IGR is absolutely central to that.”

Last summer, Chalmers wrote an essay for The Monthly calling for a new values-based capitalism. While he should have made more of his belief in the innovation, efficiency and productivity that comes from dynamic market-based economies, the response from right-wing critics was berserk. Chalmers has always believed in aspiration, opportunity and growth in economic policy.

“My point was how do we more closely align what we want in our communities with what we want in our economy?” he says.

“How do we better design and inform markets to do that? How do governments and businesses better collaborate on some of those goals? Because if our success in the next generation will be determined by how we use energy and how we adopt and adapt technology, then we need to think differently about how we approach that.”

Inquirer can reveal that Chalmers will use budget statement four to examine these longer-term structural shifts in the economy: climate change and decarbonisation; the impact and use of data and digital technology; and the expanding care and support economy. The Treasurer sees the energy transition as an especially crucial challenge for Australia.

“Cleaner and cheaper energy is obviously critical to getting people’s costs of living down and businesses’ running costs down, but it is more than that,” he says.

“This will be the biggest part of our growth prospects into the future. Whether we succeed in or fail in what will be a defining decade for this country will be largely determined by how we manage and maximise this energy transformation.”

Chalmers was born in Rochedale South and grew up in Springwood, outside Brisbane. His mother was a nurse and midwife, his father a courier driver. He was elected to parliament in 2013. He is not the first Treasurer with a PhD or the first from Queensland.

But no chief of staff to a treasurer has become treasurer before. Although he had never been a minister, his time working for Wayne Swan gave him a unique preparation in the role and responsibilities of treasurer.

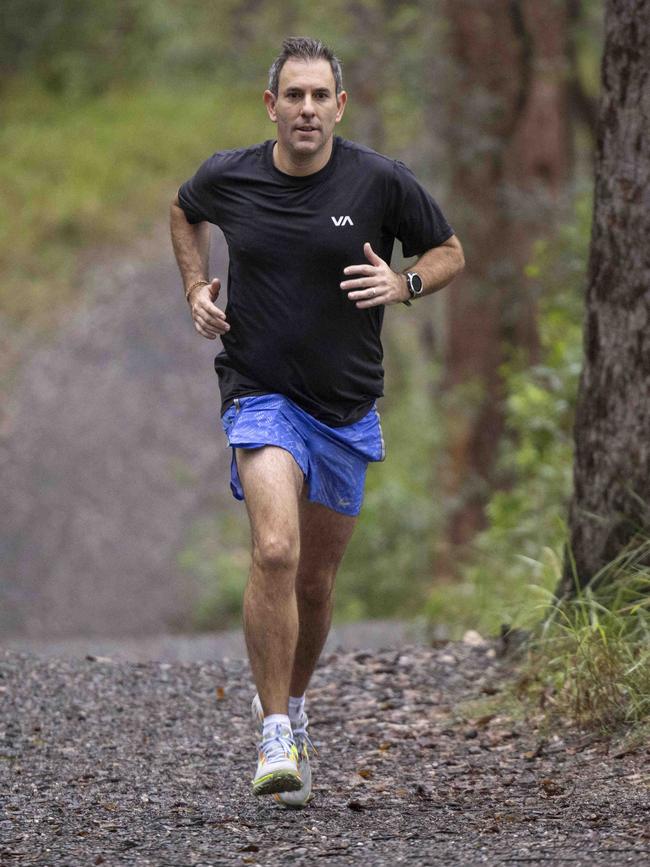

Although energised by the job and eager to be a long-term Treasurer, Chalmers admits to being more tired than he was a year ago. He still reads widely for work and recreation, and has started Jon Meacham’s biography of Abraham Lincoln, And There Was Light (2022). Once a big drinker, he gave it away completely. He has not had a drop in years. He jogs regularly. When he runs past Peter Corlett’s twin statue of John Curtin and Ben Chifley in the Parliamentary Triangle, he routinely pats one of them on the shoulder.

The only downside to the job, Chalmers says, is being away from home in Springwood and missing his wife, Laura, and their three children – Leo, 8; Annabel, 6; and Jack, 4. “You try and be the best dad you can when you’re around,” he says. “They have not actually known anything else because I’ve been a member of parliament for longer than I’ve been a dad.” He says seeing the kids recharges his batteries.

Looking ahead to next Tuesday’s budget, Chalmers says there have been several “50:50 calls” in meetings of the expenditure review committee of cabinet and the task was to find that difficult balance between the present and the future.

“One of my hopes for this budget is that people recognise our efforts in the near term on cost of living but also our efforts to lay the foundations for another generation of growth,” he says.

“So, we want to see people through and we want to set the country up, and those are the two jobs of the budget.”

Treasurers have to be focused on the short term and the long term, they must deal with the demands and necessities of the present while having a policy strategy for the future, and they must be responsive to economic and financial circumstances while seeking to shape those conditions. It is why every budget is a high-wire balancing act.