Australia sought autonomy for East Timor – its liberation was a surprise

The official history finds that Australia resisted East Timor’s independence – indeed the vote for it came as quite a surprise.

The official history of Australian operations in East Timor reveals that the drafting of this critical letter – one of the most important sent by a prime minister – was not shared with the Defence Department and senior military figures, and they were not aware it had been sent.

Yet, just nine months later, the Australian-led 22-nation International Force East Timor (INTERFET) was the largest Australian deployment since World War II.

It represented a significant policy reversal for Australia, a strategic risk, and the ADF was not fully prepared to carry out this critical mission.

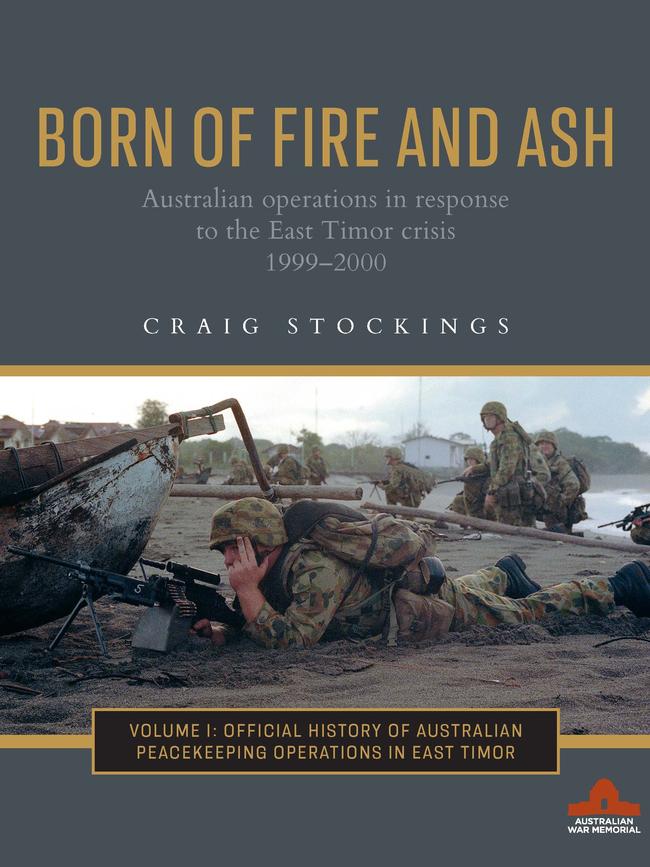

These are just some of the astonishing conclusions in Born of Fire and Ash by Craig Stockings, the official historian of Australian operations in Iraq, Afghanistan and East Timor. He is professor of history at UNSW Canberra and served as an infantry officer with INTERFET from 1999 to 2000.

It is the latest volume of official war histories sponsored by the Australian War Memorial. Stockings follows in the tradition of historians that began with Charles Bean and includes Robert O’Neill, Peter Edwards and David Horner. But there has been no official book launch, no government statement welcoming publication, and minimal media coverage.

The writing and researching of the book was enveloped in controversy. While Stockings and his team were given access to classified records and interviewed hundreds of people, it took three years for the Foreign Affairs Department to green light publication because of demands to change the text.

“We write from classified sources, and it is only proper for our product to be cleared for public release,” Stockings said. “What becomes ambiguous, however, is when real or substantive issues of information security end, and where official preferences and reputation management begins.”

The headline conclusion of this mammoth study will not make for comfortable reading for many who were involved at the highest levels of decision-making and implementation regarding Australia’s involvement in East Timor.

The official history finds that the Howard government resisted East Timor’s independence and, moreover, the intervention represented a reluctant reversal of policy consensus. “There was, to be blunt, a chasm between what the government wanted to achieve in East Timor in late 1998 and what was actually achieved by February 2000,” Stockings writes.

Australian policy since the Indonesian invasion of East Timor in 1975 was bipartisan. The relationship with Indonesia was seen as more important than the human rights and liberties of the East Timorese. Australia supported East Timor remaining part of Indonesia. This was realpolitik. Time and events forced a reversal of this policy.

“It was a policy continuity, however, increasingly out of step with the will of the Australian community,” Stockings says.

“Tens of thousands marched in Melbourne and Sydney in support of helping the plight of the East Timorese and for their right to self-determination, and thus in direct opposition to official policy.

“The dominant public narrative of Australian officialdom acting to ‘save’, ‘liberate’ or exercising a ‘duty to protect’ the East Timorese is simply not borne out by historical facts,” says Stockings. “Government policy was the precise opposite, until forced by circumstance and public outcry to reverse its course.”

Peter Varghese, head of the international division in the Prime Minister’s Department, and later secretary of the Foreign Affairs Department, says there has been “a post-event rewriting of history” about Australia being the “liberator” of East Timor. It was never the objective.

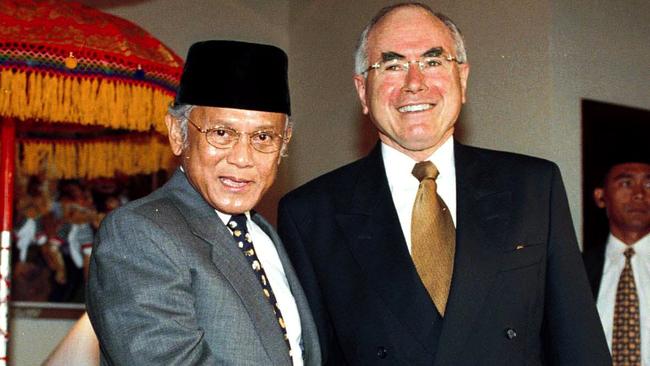

The Howard letter to Habibie was drafted with input from a small group of officials in the Prime Minister’s Office and Foreign Affairs Department, instigated by foreign minister Alexander Downer. Howard wrote that Habibie’s offer of autonomy was “bold” and provided an opportunity for “a peaceful settlement” on East Timor.

While Australia’s support for Indonesia’s sovereignty remained “unchanged,” Howard encouraged negotiations with East Timorese leaders and consideration of their demand for “an act of self-determination”. He noted the Matignon Accords which enabled a “political solution” for New Caledonia and deferred a referendum on the French colony’s “final status” for “many years”.

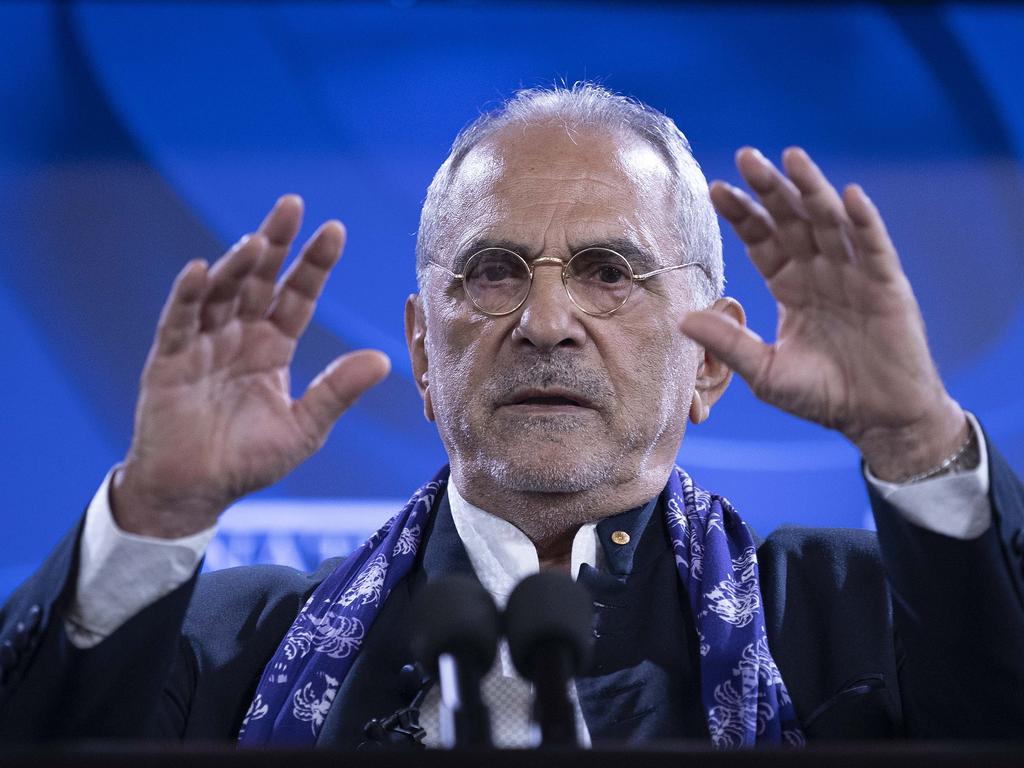

Habibie’s response shocked Australian policymakers. The president felt pressured and decided on a free vote on autonomy or independence overseen by the UN to take place in August 1999. East Timorese leaders Xanana Gusmao and Jose Ramos Horta thought up to 10 years of autonomy would be necessary to prepare for independence.

It was a time of economic turmoil and political transition in Indonesia. The Howard cabinet was concerned the IMF bailout following the Asian financial crisis was “detrimental to restoring international confidence in the Indonesian economy”. President Suharto was forced from office in May 1998, replaced by Habibie.

The Howard cabinet received reports of violence instigated by militia groups, aided by Indonesian military, in the lead-up to the vote. Howard raised with Habibie “the possible deployment of a UN peacekeeping force” in the event that a majority voted for independence. Habibie would not agree.

The Indonesian president resisted peacekeepers even as violence escalated when the vote result was announced. Following further pressure from Bill Clinton, INTERFET, led by Peter Cosgrove, deployed in September. A UN peacekeeping force took over in February 2000. Defence minister John Moore told cabinet that he favoured “an earlier transition”.

Stockings portrays Canberra as reluctant to deploy to East Timor, its hand forced by events beyond its control. He argues Australian officials “never sought” independence “until the choice was made for them”. He further writes: “Having spent much of (1999) trying to shape events in East Timor to ensure it did not have to deploy a peacekeeping force, or if it did to keep it as small as possible, Canberra was locked into its path by events in the province itself.”

The official history judges the ADF not adequately prepared, and the deployment exposed flaws in organisation and capability. But the overall mission was a huge success because the ADF was well-led and flexible, and met little resistance. While Cosgrove deserves the lion’s share of credit, it is argued others in key military roles have not been given the recognition they deserve.

Mission success came despite the ADF’s institutional weaknesses. The Defence Department had endured years of “efficiency” cutbacks and had become “hollow”, writes Stockings, “unsuited to a large-scale overseas operation” like INTERFET. As a result, “preparedness and force structures were found wanting” at the time of the rapid build-up in East Timor.

“When asked to deploy in numbers not seen since Vietnam, the ADF did its job and did it well,” says Stockings. “Yet it was a close-run thing, even in the context of a non-contested environment. That the deployment was successful was testament to the skill, professionalism and dedication of individuals.”

While veterans justifiably remain proud of their service in East Timor, Stockings writes that there is some lingering concern that they were working with elements of the Indonesian military which had perpetrated violence against East Timorese.

The book, at 921 pages, is comprehensive. A second volume on East Timor, covering 2000 to 2012, is in the process of being cleared for publication. The Australian government has allocated $17.6m for six volumes in this series, with the remainder to focus on operations in Afghanistan and Iraq.

While the clearance process was frustrating, Stockings insists he never threatened to resign – as reported – and did not surrender the integrity of the project for the sake of “reputation management” by “officialdom”.

But at one point, he thought the book might never be published. The Australian War Memorial sponsored the book and its logo is on the cover. However, it has done little to promote it.

A launch was scheduled and then postponed. Stockings has been invited only to a “conversation” event with new chair Kim Beazley in March, three months after publication. (The Australian War Memorial tells Inquirer they have “assisted” with promotion “where required”.)

Volumes of Australia’s official war history have often been launched with considerable publicity, support from ministers and departments, covered extensively by the media, and debated in think tanks, institutes and universities. Stockings says the lack of a launch or promotion by government is “curious” and “not consistent” with past practice.

Edwards is the official historian of Australia’s involvement in Southeast Asian conflicts from 1948 to 1975. He authored and co-authored multiple volumes that cover the Malayan Emergency (1948-1960), Indonesian-Malaysian Confrontation (1963-1966) and Vietnam War (1962-1972).

“Born of Fire and Ash is a superb piece of historical scholarship,” Edwards tells Inquirer. “Its independent and balanced assessments are based on extensive research in Australian official records and other sources. The Australian government should be as proud of this volume as previous governments have always been of supporting the five earlier series of official histories.”

John Howard tells Inquirer that he disagrees with some of the conclusions in the book. He acknowledges the longstanding bipartisan approach that existed towards East Timor and says he was not “agitating” for that to change when he became prime minister.

“Because of the continued anti-Indonesia activity in East Timor, and changes in international opinion, and very particularly the coming to power of Habibie, we decided over a period of months, and very particularly after the 1998 election, to change our policy,” he says. “I never proposed that independence be an option.

“In the lead-up to the vote, I had a meeting with Habibie in Bali where I proposed the insertion of peacekeepers, and he rejected that.

“I remember in the lead-up to the ballot I was criticised by some for not sending peacekeepers.

“If it is alleged that we opposed the deployment, or were reluctant, that is absurd. Once it became apparent after the decisive vote for independence that peacekeepers would be needed, I was determined to provide those peacekeepers. I made it very clear that we would expect to lead the peacekeeping force.”

Stockings recognises that former politicians, public servants and military figures may find this book challenging and have different perspectives.

“We must tell the truth as we find it, and we must go where the evidence leads,” he says. “We must be able to tell the bad with the good. To fail to do so, to take what might be an easier path, is to betray the 100-year tradition of official history in this country. It would be a betrayal, too, of veterans whose story this is. And it would be a failure to the public who have a right to know what happened – even if it is uncomfortable.”

Born of Fire and Ash: Australian Operations in Response to the East Timor Crisis 1999-2000 is published by UNSW Press.

When John Howard wrote to BJ Habibie in December 1998 offering Australian support for an autonomous East Timor within Indonesia, the president seized on the letter and weeks later announced that a vote on autonomy or full independence would take place. The letter was a catalyst for Indonesia’s change in policy towards East Timor.