Australia has changed. The Coalition’s existential problem is that, as a political party, it has failed to change with it.

This is not the country it was in the 1960s, or the ’80s. It is no longer even the Australia of the ’90s and early 2000s.

Something deeper at play has passed by the Coalition that, at a parliamentary and organisation level, it has failed to grasp, despite multiple warnings.

This is its worst defeat for the Liberal Party since its formation. The depth of the calamity cannot be overstated. But of all the mistakes that led to this result, one was fatal – the untested and superior assumption that Labor was out of touch and unaligned with the mainstream values of Australians. There can be no other interpretation than that this is fundamentally and evidently wrong.

The May 2022 election hinted at this mistaken course. Saturday’s election result confirmed it. It is the Coalition that is now out of touch with Middle Australia, while perhaps not entirely out of step with its values, but certainly its expectations. This is not only a problem of policy settings and political posture, but one of its foundational and organisational structures.

Its entire political operation collapsed at the weekend, weakened from its parliamentary and organisational leadership down to its membership, to the point that uncomfortable questions, not dissimilar to those Robert Menzies first posed in 1943, will need to be asked.

The party’s post-2022 review issued a warning that more than hinted at the structural problems. These went unheeded.

“An important element of the party identifying potential candidates is to ensure preselectors have a representative mix of the community to choose from,” its authors, Brian Loughnane and senator Jane Hume, wrote. “To successfully win seats, the party must reflect modern Australia.”

It noted that in 2022, the party lost nearly all of its inner-metropolitan seats. It lost 13 seats in total, with six to Labor, five to the teals, one to the Greens and another to a redistribution. That left the Coalition with just four. Of outer-metropolitan seats, it lost five, to leave it with 16.

After this election, in Melbourne for example, it is likely to end up with none. And this was meant to be the source of the Coalition’s revival.

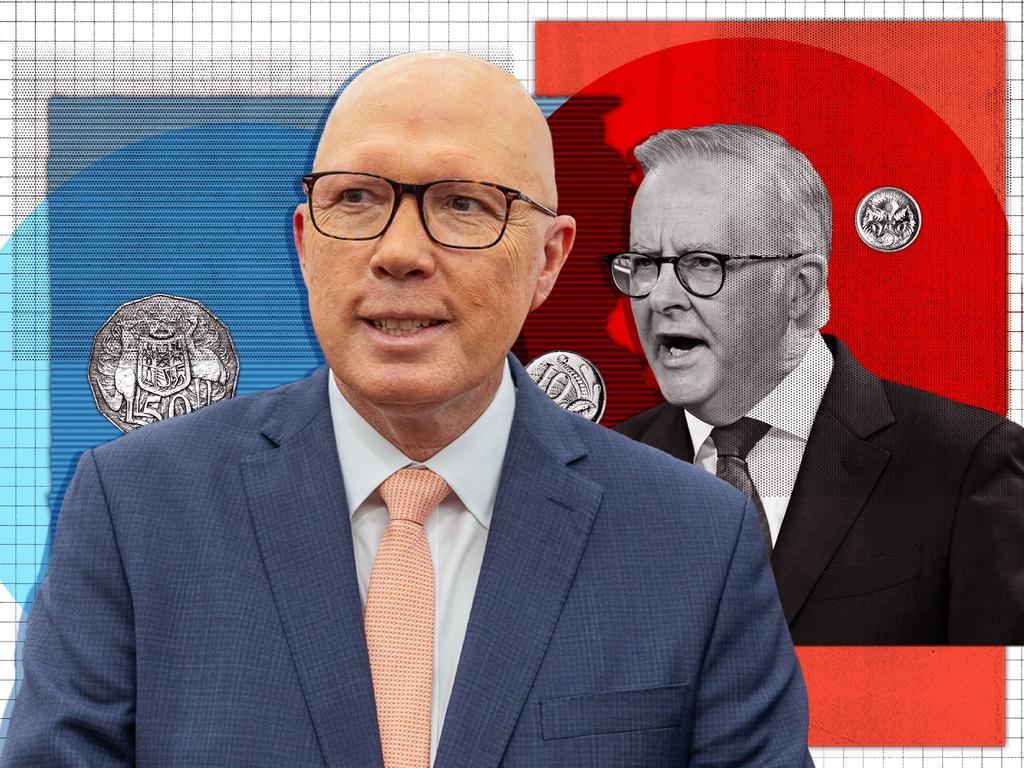

The temptation will be to make this all about Peter Dutton and blame it on him, as the party did with Scott Morrison and as Labor did with Bill Shorten.

And there are elements of that which remain true. Dutton wasn’t likeable. Labor made sure of that.

The Liberal Party ran a particularly poor campaign. Dutton was forced into error after error. And in the end it ran with the wrong policy settings, confusing economic management and ideology with the politics of the household economy. The decision to fall for Labor’s bluff on tax cuts was a fatal mistake in itself.

There will be endless debate about the technicalities of the campaign, the post-voice strategic direction and the absence of good policy development. Tactically, the Coalition has also been outplayed at every move since the beginning of the year, with Anthony Albanese having played error-free footy since January.

This was the most prolonged period for Labor of anything resembling competent management during the entirety of its term. It washed away many of the sins of the past.

People have been living in a cost-of-living crisis for two years. People are materially worse off than they were before Labor was elected. These should have been difficult conditions for an incumbent. But this only reinforces the point that the Coalition has also failed to wake up to deeper changes that have been occurring.

Opposition Treasury spokesman Angus Taylor recognised the cyclic nature of dependency on the state that developed post-Covid. The Coalition was bargaining that this cycle could be broken through an appeal to aspiration and self-determination. He would talk of a hand up rather than a handout. And in the past, this had been true enough.

On this occasion it wasn’t. The immunity card that Labor was offering to voters to ride out the cost-of-living trough – despite the longer term fiscal and economic consequences – remained the more attractive model for most Australians.

But the deeper problem lies with who the Liberal Party now appeals to. It’s most significant problem is with women. This cannot be put down to the Trump factor alone, and the success of Labor in drawing comparisons with Dutton politics and Coalition policy.

The Coalition also over-estimated the anti-woke movement, its breadth and depth in Australia. It exists, of that there is no question. But was it significant enough to make a difference? Clearly, not at all.

As Morrison once said of the culture wars and his reluctance to engage in them, they don’t put food on the table.

In the 2022 Liberal Party review, the party’s structural and policy settings in appealing to women was one of the more dramatic of the warnings about the challenges ahead. That and the drift from ethnic communities.

The report said: “The Liberal Party performed particularly poorly with female voters, continuing a trend that has been present since the election of 1996.

“The results from the 2022 campaign include: A majority of women preferred Labor in all age segments (18-34, 35-54 and 55+).”

This was a critical factor in the party’s defeat then, as it is now.

“The party, since inception, has prided itself on pioneering gender equality in its office bearer positions,” it said.

“However, the party has clearly fallen below this proud record in the number of women representing the party in parliament and in the number of women who are currently members, particularly young women. In recent years the party has not been attracting new members in the numbers necessary to campaign effectively in local communities, particularly members who are ethnically diverse, women and under 40 years old.

“Immediately following the election, a clear majority of Australians (across different electorates) agreed with the statement that ‘the Liberal Party has fallen behind the views of Middle Australia’.”

At a broader level, the report and the 2025 election result can be interpreted as suggesting it was the Coalition, rather than Labor, that is no longer aligned with modern Australia.

The Coalition is likely to focus on the campaign disaster, and the technicalities that led to it, as well as the branch-level decay that has continued to be left largely unaddressed.

But it will ignore the deeper problem of its relationship with mainstream Australia at its peril.