Aged care ‘a shocking tale of neglect’

‘Cruel and harmful’ aged care must be reformed, a royal commission has urged.

“Cruel and harmful” aged care must be reformed, a royal commission has urged, finding the system is in a shocking state of neglect that “diminishes Australia as a nation”.

The royal commissioners, who delivered their interim report on Thursday, called out three issues for urgent attention: more funding to be provided immediately for high-need, in-home care recipients; dealing with the use of chemical restraints in residential aged care; and getting 6000 young disabled people out of nursing homes as soon as possible.

READ MORE: Analysis — findings are enough to make you weep | Wake-up call a win for families | Drugs review urges role for psychiatrists | Abuse still haunts victim’s son | Deadly aged-care practices ignored | Royal Commission chair Richard Tracey dies | ‘No leadership’ on young people in aged care

Commissioners Lynelle Briggs and Richard Tracey, who has died since the interim report was finalised, were damning in their assessment.

“The neglect that we have found in this royal commission, to date, is far from the best that can be done,” the commissioners said.

“Rather, it is a sad and shocking system that diminishes Australia as a nation.”

In a brutal critique of the broader aged-care system after months of testimony from providers, experts and care recipients and their families, and thousands of submissions, the commission has highlighted systemic failures.

“It (the system) does not deliver uniformly safe and quality care, is unkind and uncaring towards older people and, in too many instances, it neglects them,” the commission concludes in its report, simply entitled “Neglect”.

“This cruel and harmful system must be changed. We owe it to our parents, our grandparents, our partners, our friends.

“We owe it to strangers. We owe it to future generations. Older people deserve so much more.”

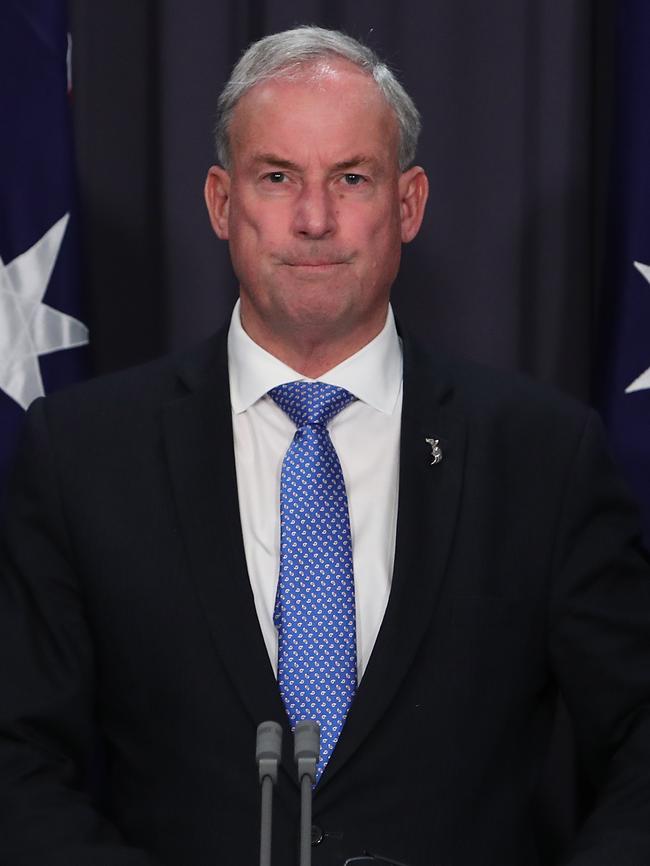

Federal Aged Care Minister Richard Colbeck said the government had been “shocked” by the extent of the issues uncovered by the commission to date, and the findings had put the government on notice.

“It’s done that in spades. It’s put the government on notice. It’s put the industry on notice. As importantly as anything, it’s put the community on notice,” Senator Colbeck said.

More than 1.2 million Australians accessed aged-care services from mainstream programs in 2017-18, including: about 850,000 receiving basic services under the Commonwealth Home Support Program; 120,000 who received a Home Care Package of more intensive supports and services; and 240,000 who received permanent residential aged care.

Thousands of others receive informal care from friends and family.

The commission’s report, tabled in federal parliament, highlighted a number of critical issues that had arisen through the nationwide hearings to date, including: difficulty in accessing all forms of aged-care services; the “dispiriting” nature of residential care; substandard care; and unsafe practices.

“And there is an underpaid, undervalued and insufficiently trained workforce,” the commissioners added.

Beyond government policy and industry neglect, the commission called out community attitudes to older people.

“As a nation, Australia has drifted into an ageist mindset that undervalues older people and limits their possibilities,” it said.

“Sadly, this failure to properly value and engage with older people as equal partners in our future has extended to apparent indifference towards aged-care services. Left out of sight and out of mind, these important services are floundering. With some admirable exceptions, they are poorly managed. All too often they are unsafe and seemingly uncaring. This must change.”

The commission said there had been too many examples of unacceptable practices in aged care, including inadequate wound and continence management.

“(There was) dreadful food, nutrition and hydration, and insufficient attention to oral health, leading to widespread malnutrition,” it said.

The commission also highlighted a high incidence of assaults by staff on residents and by residents on other residents and on staff.

“And there was widespread over-prescribing, often without clear consent, of drugs which sedate residents, rendering them drowsy and unresponsive to visiting family and removing their ability to interact with people,” it said.

“It is shameful that such a list can be produced in 21st-century Australia.”

The commission called out providers for labelling those in their care as “difficult” if they complained, leaving care recipients and their families fearful of receiving worse treatment.

“Some providers of aged care have appeared before the royal commission to be defensive and occasionally belligerent in their ignorance of what is happening in the facilities for which they are responsible,” the report says.

“Providers were reluctant to take responsibility for poor care on their watch. Some providers have shown an unwillingness to accept that they could have, and should have, done better.”

The commission said the regulatory regime that was supposed to be ensuring aged-care services were being delivered safely and with high quality was “unfit for purpose” and didn’t adequately deter poor practice, or in many cases even detect them.

Workforce issues had been a constant theme for witnesses at the commission, it said. “Workloads are heavy. Pay and conditions are poor, signalling that working in aged care is not a valued occupation. Innovation is stymied. Education and training are patchy and there is not defined career path for staff. Leadership is lacking. Major change is necessary to deliver the certainty and working environment that staff need to deliver great quality care.”

Sarah Holland-Batt, who appeared at the commission’s Brisbane hearings in March to speak of her father Anthony’s experiences of abuse in a Gold Coast nursing home and her frustration with the ACCC’s subsequent investigation, said she was far from shocked at the interim findings.

“I saw the Aged Care Minister say he was shocked,” she said. “I’m not shocked, because there have been 20 or so similar reports or inquiries in the last two decades that all made similar findings and recommendations — they haven’t been implemented, and here we are again.” She said she was concerned about the government’s appetite for reform.

The commission’s interim report was developed from evidence up to July, with some elements of more recent hearings included. It will sit next year, and hand down a final report in November 2020.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout