After the fires, we’ll have combustive issues to resolve

Not much could have prevented this week’s fires, but we have combustive issues to resolve.

The politics of climate change touch most aspects of life. This trend will intensify, since the changing climate invades almost everything. It was inevitable the NSW government’s “catastrophic” rating of the fires would deepen the polarisation on this issue.

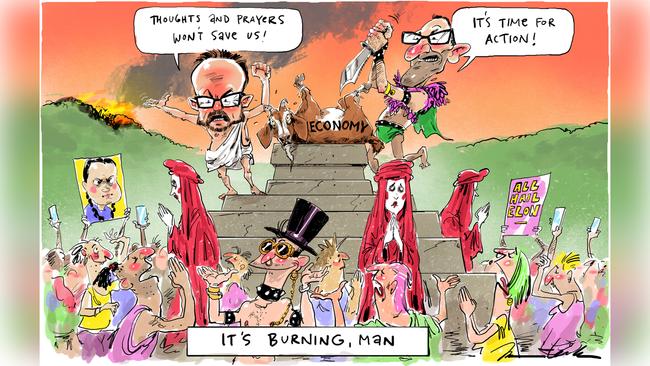

The Greens exist for the politics of climate change, so manipulating the destruction of lives and property in this cause is no surprise. It is their core business and belief set. If people find it loathsome, the Greens will live with that. They ride an existential movement — the global lurch to extreme climate policy from the Green New Deal in the US to the Extinction Rebellion protesters in the cities of the West.

READ MORE: LIVE — Follow the latest on the bushfire crisis in our blog | Chris Kenny says the Left’s climate lunacy is dangerous, offensive | Days now weeks for exhausted heroes | Ill winds reignite menace | Relief as armageddon avoided | Military may be put in firing line | Another blow for face of bushfire crisis | ‘Obnoxious uncle’ Joyce under attack

The spat between senior Greens Richard Di Natale and Adam Bandt on one hand and Nationals leaders Michael McCormack and John Barilaro on the other is part of the battle for the political soul of regional Australia and how the nation should respond to the changing climate. This is about politics, not science. The science is used as a political weapon.

As the countryside burns, the Greens, defined by offensive opportunism, adhere to their business model of alarmism. The Nationals, split between the concerns of their constituents and their conservative base, betray their dilemma with McCormack branding his opponents as “raving inner-city lunatics”, a desperate effort in delegitimisation.

Contrary to the accusations of the Greens, Scott Morrison and McCormack cannot control the climate. The idea is absurd yet it underpins these hysterical exchanges. Di Natale said: “Just because we cannot tie any one individual fire to the climate emergency doesn’t mean that those who refuse to act are not responsible for these blazes.” He said the “root cause” of the fires was “the burning of fossil fuels”.

The accusation is obvious: the Morrison government is “responsible”. This is despicable — and nonsense. Climate change has not caused these fires. Its role, as many scientists argue, is to accentuate the threat and contribute to a fire season longer and more intense. But fires have long been part of the Australian story.

However, if one assumes a primary role for climate change, then that concedes the problem is global. As Ross Garnaut said of the climate change challenge: “The relevant mitigation is global.” These five words are the essence of climate change politics.

What the rest of the world does is infinitely more important than what Australia does. The global problem cannot be solved by Australia. We’re responsible for about 1.3 per cent of emissions, with the big emitters being China, India and the US. Accordingly, if you believe the fires are created or driven by climate change — as do many activists and Greens — it follows that Australia cannot solve the problem, only the global community can do that, and Morrison, sadly for your political propaganda, cannot be responsible.

If the Greens followed the science, they would ask the big emitters to do more, but that would miss their entire purpose — to play domestic politics.

Barnaby Joyce got it right when he attacked the Greens, saying: “There is nothing we have done in the Australian parliament that has brought about the absolute devastation on so many people’s lives. The only reason you are driving this agenda is for your own political purposes.” Joyce told the Greens the action that mattered would come from China, India and the US.

The point is that Australia’s action, while relevant to our own economy, is significant in terms of global warning only for our contribution to global mitigation. If you are alarmed about the impact of climate change on Australia, our landscape, our fires or the Great Barrier Reef, what matters is the extent of global mitigation.

The Economist magazine, pledged to urgent action, has still kept its head: “It is important to understand all the things that climate change is not. It is not the end of the world. Humankind is not poised teetering on the edge of extinction. The planet itself is not in peril. Earth is a tough old thing and will survive.”

If Morrison had changed policy, boosted the emission reduction targets or moved against the coal industry, nothing would be different in terms of bushfires. The Greens are selling a phony proposition but they have plenty to be guilty about. A decade ago they sank Kevin Rudd’s carbon pricing scheme, another example of their manic quest for product discrimination.

However, these are not arguments against Australia doing more. They are arguments against Australia doing more on the basis of false propositions. The certain story is that the politics of climate change will shift dramatically over the next three years and the policy Morrison took to the election in May will not suffice in 2022. That must be obvious to the Liberal and Nationals parties. If they fail to discern this, they will be lost in the political hurricane.

Assaulting the Greens will be the easiest part of the adjustment as the global climate change debate erupts into more radical dimensions; the resort to civil disobedience and violence testifies to frustration with the democratic system itself, while the campaign to decarbonise economies has generated a movement against capitalism in favour of a socialist economy. These trends will not help the cause. But its radicalism cannot disguise the ongoing momentum for government action.

Forget the historical statistics. The experience of the fires only deepens the public’s view that the climate is changing, a point frequently made by Morrison. The aspirational idea of net zero emissions by 2050 is taking off. It has been embraced by state Liberal governments and many major corporates, and appeals to the environmentally aware middle class. Moreover, by the 2022 election, targets beyond 2030 will be on the table.

Morrison cannot be left behind. His task will be to move to a new balance between his conservative base and the advocates for more direct and aspirational change. It is because he seeks to govern from the middle that he will need to make this adjustment. The context will be how Australia interprets its proportionate contribution to global mitigation.

Morrison has been prudent in focusing on the operational aspects while the fires are burning and refusing to discuss the politics. But he has built up expectations that he will talk afterwards — and that is essential. He will need to reframe his stance: that means stronger recognition of climate change reality and more comprehensive “on the ground” plans with the states and local councils to meet the fire threat that is now semi-permanent.

The longer-run issue will be climate change policy. In 2015, the Abbott government decided on an emissions reduction target of 26-28 per cent off 2005 levels by 2030 in the context of the Paris conference. That was at the distinctly lower end of pledges by industrialised nations but was significant in terms of per capita reductions.

The Abbott cabinet rejected any view that because Australia contributed only 1.3 per cent of global emissions it should make no contribution to the global effort. Its targets have been highly successful — backed by three prime ministers, Tony Abbott, Malcolm Turnbull and Morrison, they have broad internal support and have been taken to and endorsed at two elections.

Morrison’s immediate problem is not the target but the absence of a domestic policy geared to emission reductions, energy reliability and lower power prices.

Meanwhile, the argument for climate action is going to shift in a new direction. In his new book Superpower, Ross Garnaut argues that robust action will serve Australia’s national interest because the nation can evolve as a low-cost, renewable-energy superpower, a practical economic argument likely to get more traction than fears and scares.

It is an unfortunate truth that there is no silver bullet for politicians or firefighters to protect against raging bushfires — but such fires are now a political commodity in the transformed norms and values driven by climate change.