My 'arch of opinion'

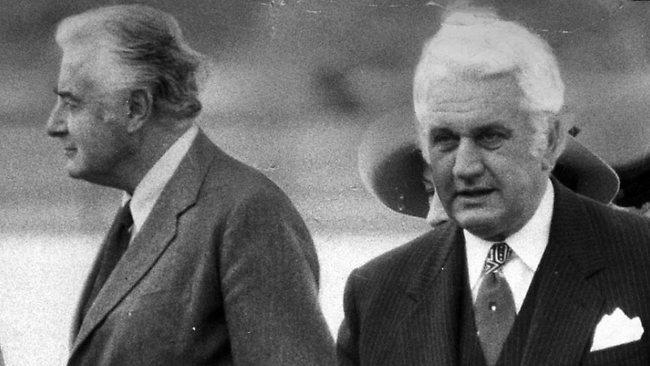

KERR reveals the men who reinforced his dismissal decision.

THE newly released personal papers of John Kerr reveal his concept of an "arch of opinion" among his old friends on the High Court and Sydney Bar from whom he drew emotional and intellectual backing in planning Gough Whitlam's dismissal.

The "keystone" in Kerr's "arch of opinion" was his friend and High Court judge Anthony Mason, later chief justice. New documents show Kerr relied on Mason to repudiate the advice of the prime minister, Whitlam, in the events leading to the 1975 dismissal of the Labor government.

The Kerr papers now released by the National Archives reveal that Mason at critical points of the crisis sustained Kerr in his defiance of Whitlam and in planning his dismissal.

Kerr nominates Mason, along with then chief justice Garfield Barwick, as integral to what he describes as the "arch of opinion" telling him the dismissal power did exist and could be used. He included in this group former solicitor-general RJ Ellicott, then an opposition frontbencher, whom he had known at the Sydney Bar.

But Mason was the pivotal figure. Kerr reveals he played an earlier role in having Mason appointed as solicitor-general when he advised then Liberal attorney-general Billy Snedden that "he could not go wrong with Mason".

Kerr's papers implicate the High Court in Whitlam's dismissal even beyond Mason and Barwick. He claims that another judge, and future governor-general, Ninian Stephen, was aware of the pending dismissal and did not dissent. Kerr says he lunched with Stephen on May 15, 1981, and "it is clear from my conversation with Stephen that he did not attempt to dissuade Barwick from giving the advice and my understanding of what he said was that he, as well as Mason, saw the draft he (Barwick) prepared that morning".

This contradicts Stephen's previous 1995 denial and statement that "I knew nothing until the news broke publicly". At this point Stephen's role remains contested.

The Kerr-Mason friendship and dialogue during the crisis, as revealed in Kerr's papers, offers an extraordinary insight into Whitlam's dismissal. While their versions contain significant disagreements, there is no denying the value Kerr placed on Mason's views, the extent of their discussions and Mason's role in fortifying Kerr's dismissal decision.

The previous knowledge of Mason's role -- namely, that he just endorsed the view expressed in Barwick's written advice to Kerr -- is now exposed as only a small part of Mason's involvement.

Kerr details Mason's role in two documents. The first is his personal note of October 21, 1975, after the first week of the crisis, triggered by the legal opinion from Ellicott. The second is another note written by Kerr in London in the first half of 1981, after a three-month holiday in Australia "during which I saw Mason several times".

Kerr says of Mason: "I regarded him, I still do, as a liberal-minded and progressive man and lawyer, of judgment and wisdom, as well as of learning and all-round intellectual quality, and believed that no one could better, by conversation, help me to sort out my own thoughts on the constitutional powers of the governor-general in the constitutional crisis of 1975.

"It is only the magnitude of the 1975 crisis itself which makes historically important what happened between Mason and myself. But it is truly relevant because my conversation with Mason helped me to fortify myself for the action I was to take."

Kerr says in his talks with Mason "the existence of the reserve powers was taken for granted". The Kerr papers document his barely concealed contempt for the view of the government's law officers and his reliance, instead, on his preferred "arch of opinion".

Nothing better illustrates this sentiment than Kerr's note on October 21 that "in the end, the final crunch, I have no escape from the duty to assert that the reserve powers of dismissal and dissolution still exist and can in extreme circumstances be exercised and a joint opinion of the law officers to the contrary would certainly not deter me if the moment arrives for action".

His alienation from the views of the law officers (attorney-general Kep Enderby and solicitor-general Maurice Byers) is pervasive.

Kerr writes he had a long private talk with Mason on October 12, a few days before the budget was blocked, that related to the reserve powers.

"It was a helpful conversation the main purpose of which was to enable me to talk aloud to a friend," he writes.

Mason, in his article of August 27 in The Sydney Morning Herald (his only statement on these events), says the first discussion with Kerr was earlier, in August, before their subsequent talk on or around October 12.

The governor-general writes that he and Mason "had a running conversation" during the crisis. Reflecting on his relations with Mason, he says "the intimacy of our friendship was maintained" after Kerr became governor-general and Mason went to the High Court.

At the Government House dinner on October 16 to honour Malaysia's prime minister Tun Abdul Razak, opposition leader Malcolm Fraser went out of his way to tell Kerr about the Ellicott opinion that argued Kerr should dismiss Whitlam. This opinion triggered a series of events and Kerr decided, as a result, he wanted a formal opinion from the law officers on the Ellicott memo.

On October 19, Kerr asked Whitlam if he could consult with Barwick on the crisis and Whitlam was emphatic: he told Kerr he could not speak to Barwick. But Kerr had an even better alternative: he spoke to Mason.

According to Kerr's October 21 note, he spoke to Mason the previous day, October 20. Kerr writes he told Mason that he had asked Whitlam for an opinion from the law officers on the Ellicott opinion and Mason agreed with this move. Kerr says he asked if Mason would give him his personal views on both the Ellicott opinion and the law officers' opinion (when it came) and says that Mason agreed. Indeed, Kerr writes that Mason is "prepared to allow publication if it were ever needed to enable me to defend my own integrity if it came under serious attack". Mason, by contrast, says that he did not agree to provide a written opinion.

Kerr writes he spoke to Mason again the next day, October 21, the very day he wrote this note, about relations between Ellicott and Barwick and "the desirability or otherwise of seeking Barwick's formal advice".

The governor-general, referring to both conversations, writes: "His (Mason's) assessment was that I should only do so, if I felt otherwise at liberty to take this step, if I had assessed (a) what advice I really needed and (b) what he (Barwick) would be likely to advise. Today he said he believed it to be possible that Barwick believed and would advise immediate radical action -- dismissal etc. He agreed with me that to get such advice would be disastrous at this stage."

The crisis was hardly a week old. Kerr continues: "In any event the Prime Minister had made it clear to me on several occasions over the months that he took the view that, contrary to (Paul) Hasluck's opinion and despite what Sir Samuel Griffith did early in the century, I was not entitled ever to ask for the advice of the Chief Justice."

In short, Whitlam was telling Kerr not to speak to Barwick, but Kerr in talks with Mason was canvassing the timing and tactics in deciding when Barwick should be engaged.

Writing of the Ellicott opinion, Kerr says: "If Ellicott were hoping that his document would influence me to act immediately or very soon after supply was blocked, it in fact had the opposite effect. I strongly felt that time should be allowed to pass and action, if needed at all, should await the last possible moment. Ellicott took the opposite view."

Kerr says that in his talks with Mason on October 20 and 21 about seeking Barwick's advice, they both felt it would be "disastrous" at that time and Kerr explained the reasons.

He feared that Barwick's advice would be the same as Ellicott's -- urging him to an immediate dismissal, a course he disagreed with because of timing, not substance. "His (Mason's) agreement with me was a comforting judgment," Kerr writes.

In summarising his talks with Mason, Kerr says: "I always said first what I thought." He writes that Mason "never had any difficulty in talking to me about my powers and discretions" and that he "never felt that his position on the court rendered that course of action undesirable or impossible".

Kerr says Mason was "ready" to offer his opinion on both the Ellicott memo and the law officers' reply. "He saw no difficulty in my consulting Sir Garfield Barwick except considerations of timing and tactics," he writes.

As the climax approached, Mason's SMH account says that he and Kerr met on November 9 at North Sydney, away from Admiralty House, because Kerr "did not want the Prime Minister to know of our meeting". Their accounts are the same -- Kerr begins by saying he had decided to dismiss Whitlam and commission Fraser as a caretaker to advise an election.

According to Kerr's account, Mason said: "I am glad of that. I thought that I might this afternoon have to urge that course upon you." Mason says that at the end of their conversation "I expressed my relief that Sir John had made a final decision to resolve the crisis by dismissing the prime minister because I thought that the crisis should be resolved by a general election to be held before the summer vacation and any further delay could lead to instability".

Mason says his remark "was not and should not" be seen as encouraging Kerr to dismiss Whitlam. It is, however, almost impossible to draw any other conclusion. The accounts of Kerr and Mason agree that at this meeting Mason offered his views on the "draft" opinion from the law officers. Kerr says he told Mason he felt the Byers opinion was "quite wrong" in that Byers said the reserve powers "existed" but "might have fallen into desuetude". Kerr says he believed the reserve powers "still existed and could be used". He says Mason agreed.

This is consistent with Mason's version. "I don't agree with it," he said of the law officers' opinion according to his own account.

They discussed obtaining Barwick's opinion.

Kerr writes: "I did not want Barwick's views on what I should do but only on what I could do. He (Mason) said I would have to make that clear."

Kerr says he felt Barwick's view on the existence of the dismissal power would be important.

He writes: "Mason did not dissent and did not urge any argument that, if Barwick gave such advice, it would damage the court. He did not seek to dissuade me from talking to Barwick. Indeed, he encouraged me to do this. I rang Barwick in Mason's presence and he agreed to see me the next day." According to Mason the two men and their wives dined that night.

Mason says he repeated his earlier warning to Kerr that he should give Whitlam the chance to go to an election as prime minister, a point that does not appear in the Kerr papers. That is hardly a surprise.

Mason says that, in response to Kerr's request, he drafted a dismissal letter, a draft that Kerr evidently did not use. He rejects Kerr's claim that Mason provided material for the governor-general's statement explaining his dismissal decision.

When Barwick, unaware of the previous Kerr-Mason dialogue, showed to Mason his letter of advice to the governor-general approving the dismissal, Mason replied: "It's OK." Kerr had manoeuvred successfully to have both judges with him.

In his papers Kerr says he wanted Mason's full role to have been revealed during Kerr's lifetime. But that did not happen. "He (Mason) would be happier for the sake of the court if history never came to know of his role," Kerr writes.

But Kerr was determined to have it revealed. This is the reason he wrote such an elaborate note on Mason's role as the keystone in the "arch of opinion".