The government has signed up to a plan that is so extreme and unworkable it will galvanise the No case by ignoring the problems that have come to light since a preliminary version was unveiled last July.

Instead of fixing those problems in order to split the No vote, the government of Anthony Albanese has appeased the extremists within its own Indigenous working group on the referendum.

Reasonable people who were waiting to see the final form of the proposed constitutional amendment have just been given the green light to vote no.

Explicit constitutional recognition of Indigenous people was a late addition to this project – and it shows. It seems the real goal has always been to establish an institution of state that would turn back the clock to the days when racial privilege dictated public policy.

Instead of standing up for the egalitarian principles of modern Australian democracy, the government has adopted a proposal that would entrench racial privilege by exposing ministers and public servants to the risk of legal liability.

The executive branch of government would be subjected to a new system of accountability in which real power – the power to sue – would be vested in a race-based institution whose members would not necessarily be elected by anyone.

Worst of all, the government knows this proposal is flawed.

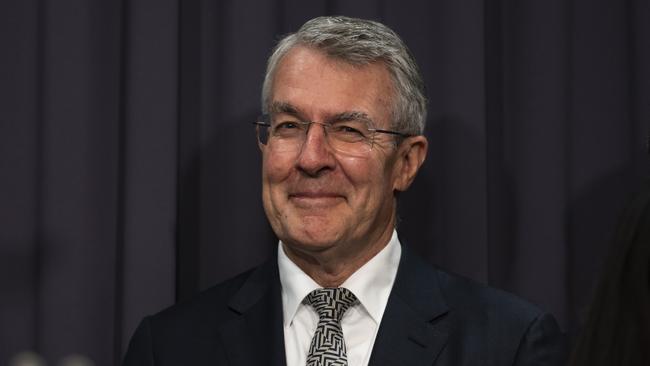

Days ago, Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus tried to persuade the referendum working group to change the provision that would establish the voice and give it authority to make representations not just to parliament but to the executive branch as well.

Yes, there is a legitimate argument that Indigenous people should be heard before parliament makes special laws about them under the Constitution’s race power in section 51 (26) but there is no case for extending the reach of the voice into the executive or to matters that go beyond special laws under section 51 (26).

When working group members chastised Dreyfus for suggesting a change that could affect the voice’s impact on the executive, the government went to water. In an extraordinary display of audacity, Albanese is now pretending everything is wonderful. It’s not. And Dreyfus’s own actions show that.

Unless the voice’s reach into the executive is eliminated, it will be too late to address this problem by statute if the referendum succeeds. The High Court would then be responsible for determining the legal effect of the voice’s representations to ministers and public servants, just as it is responsible for determining the legal effect of other parts of the Constitution.

If the court decides there is a constitutional implication that ministers and public servants should consider the voice’s advice, or inform the voice before making decisions, the consequences would be disastrous.

Public administration would slow, the bureaucracy would need to expand and decision-makers would be at risk of legal liability.

Taxpayers’ money that would be better spent addressing Indigenous disadvantage would finish up in the hands of litigators.

If this referendum succeeds, every federal minister and every decision-maker in the federal public service could be at risk unless they inform the voice before making decisions, provide information about matters awaiting decision, wait for a response from the voice and generate a paper trail showing the views of the voice have been considered.

This is ludicrous. How much information will ministers and public servants be required to give the voice about decisions they propose to make?

How long would ministers and public servants need to wait while the voice considers its position?

The great tragedy for Indigenous people is that most of their fellow citizens would probably endorse a reasonable form of constitutional recognition, but the change proposed by the government is not modest nor is it symbolic.

It is wrong in practice and in principle.

It would destroy the doctrine of equality of citizenship by introducing a permanent system of racial preference when it comes to federal lawmaking and administrative decisions.

It would give Indigenous Australians a second method of influencing public policy that goes beyond the benefits of representative democracy that are already enjoyed by all citizens regardless of race.

The measures associated with the voice would be permanent and would persist forever.

That means the Prime Minister was pushing things when he asserted on Thursday that his proposed change would enhance Australia’s international standing.

Right from the beginning, when the Prime Minister unveiled his preliminary model for an Indigenous voice, it was clear that equality of citizenship – the bedrock of egalitarian Australia – would be destroyed unless big changes were made.

Yet behind closed doors, the Albanese government has decided to water down the principles of egalitarian democracy to mollify one special interest group.

Chris Merritt is vice-president of the Rule of Law Institute of Australia

What we have just witnessed in Canberra is a masterclass on how to cripple the cause of constitutional recognition of Indigenous people.