The professor, the petition, and a passion for history

The sequence of events that would lead historian Clare Wright to track down the long lost fourth Bark Petition began during the lockdown years.

The sequence of events that would lead historian Clare Wright to track down the long lost fourth Bark Petition began in Melbourne during the lockdown years.

Professor Wright – who had previously written books about the Eureka Stockade and Australia’s women’s suffrage movement – had turned her focus to the historic petitions, which had marked the start of the Indigenous land rights movement.

The petitions, written in both English and traditional languages and framed by traditional bark art, were sent to Canberra in 1963, calling for consultation with the local Yolngu clans before bauxite mining began in the area.

Professor Wright, from La Trobe University, saw a book on the Bark Petitions as the logical next pillar in her series on the history of Australia’s democracy. The petitions, she says, were to Indigenous land rights what the Eureka Stockade was to workers’ rights, and the suffrage movement was to women’s rights, and they deserved to be recognised among Australia’s founding documents.

“They were the first petitions ever put to an Australian parliament that led directly to a parliamentary inquiry, and that inquiry and its findings very much laid the path for the land rights movement in Australia,” she told The Australian.

She was trying to find Jim Wells, the son of missionaries Edgar and Ann, who were both instrumental in helping the Yolngu people of northeastern Arnhem Land with the petitions all those years ago.

She started cold-calling across the country in an attempt to find the man who had been just a boy when the petitions were compiled. When she eventually found him, he was living just a 20-minute drive from her in Melbourne and had a garage and a spare bedroom full of old documents and records to share with her.

The cache was a historian’s dream, but the Covid lockdowns of the time meant it would be many months before she could get her hands on it.

Finally diving through those records, she found confirmation not only that a fourth petition existed, but that it had been given to Stan Davey, the secretary of the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement at the time – in recognition of his assistance in getting the petitions down to Canberra.

He had long since died in 2010, so Professor Wright began trying to find his first wife, Joan McKie.

She was surprised to eventually find the 91-year-old active on Facebook. Communicating over the social media platform, Ms McKie confirmed not only that she knew the whereabouts of the missing petition, but that it was hanging in the hallway of her home in Derby, in Western Australia’s north.

Ms McKie told Professor Wright she wanted to see the petition returned to Yirrkala and it was formally handed over in November 2022, with the petition then spending months in the hands of conservators in Adelaide.

For Yananymul Mununggurr – the daughter of the last surviving signatory to the petition, Dhunngala Mununggurr – the discovery of the lost petition triggered a range of emotions.

“When I first heard they had found it, I was a bit emotional,” she told The Australian.

“I was a bit sad for the family, as they’d had it in their hands for a long time, but I was glad that they had approved for the petition to come home.”

She said the petitions were a crucial “stepping stone” for the advancement of Indigenous land rights in the decades that followed. “It was the driving force behind the Mabo case, the Aboriginal land rights act, the Native Title act, it was the driving force behind the homelands movement,” she said.

In December, the fourth petition was formally returned to Yirrkala, where it will be on permanent display at the Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre.

Two of the petitions are displayed in Parliament House, and a third is in the National Museum of Australia.

Among the hundreds of people in attendance for the lost petition’s return to Yirrkala was Mr Wells, who was returning to the community for the first time since the eventful aftermath of the petitions.

Dr Wright said Edgar and Ann were disciplined by the church over their role in the Petitions.

“The church headquarters in Sydney had done a deal with the federal government and the mining companies to excise a portion of the Arnhem Land reserve and to award mining leases to a multinational mining company,” she said. “The missionaries on the ground there hadn’t been told about it and didn’t know anything was going on until they saw all these survey pegs outside the mission boundary.”

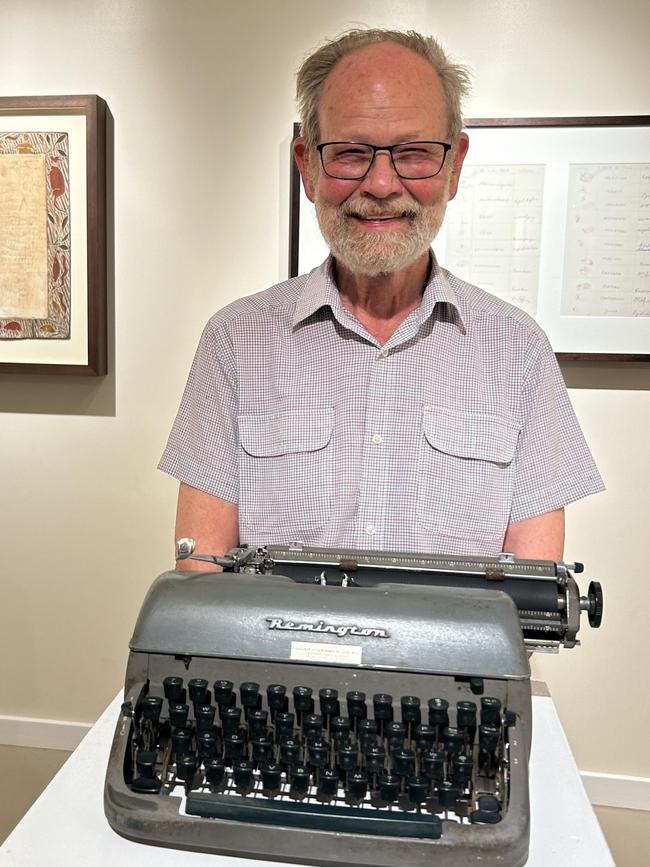

The typewriter that Ann Wells used to type up the petitions has also been gifted by Mr Wells and will be displayed alongside the petition in Yirrkala.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout