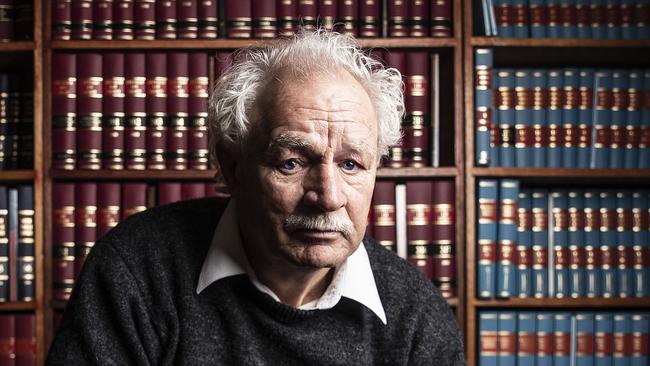

Senate seats ‘better than a voice’, says Indigenous leader Michael Mansell

Tasmanian Aboriginal leader Michael Mansell will campaign against the ‘assimilationist’ voice to parliament and is instead urging the allocation of six Indigenous-elected Senate seats.

Tasmanian Aboriginal leader Michael Mansell will campaign against the “assimilationist” voice to parliament and is instead urging the allocation of six Indigenous-elected Senate seats.

The veteran activist told The Australian the voice was a “second-grade” option and “completely counter-productive”, as it enshrined an advisory-only body in the Constitution, rather than actual power for Indigenous Australians.

“The voice is purely assimilationist and it’s a second-grade model,” said Mr Mansell, chairman of the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania.

The lawyer and attendee of the Uluru gathering that led to the Statement from the Heart said had the voice proposal been put forward by non-Indigenous people it would be have been widely condemned as “racist”.

“This has come from a very conservative section of the Aboriginal community itself so they can get away with it,” Mr Mansell said.

“It can’t force government to negotiate. Whereas, six Aboriginal delegates out of 76 in the Senate can actually vote on legislation, speak openly about Aboriginal rights and can use their voting power to negotiate deals for the Aboriginal community.”

He would not support the voice, believing it was a distraction. “Uluru was about sovereignty, truth telling and the voice – the only thing we’re hearing about is the voice,” he said.

Enshrining in the Constitution an advisory body – rather than representation in parliament – was “completely counter-productive”. “I’ll be campaigning against it (the voice),” he said.

“To enshrine in the Constitution a limit on Aboriginal empowerment – in this case limiting it to advice only – would make us the only people in the country whose right under representative democracy is limited in the Constitution to advice only.”

Mr Mansell’s proposal would see one senator among the 12 from each state elected solely by the Indigenous population.

“If Australia is representative democracy, then the make-up of the parliament should reflect the people it governs,” he said.

This would not require constitutional change.

“All the federal government has to do is to amend the Electoral Act to say of the 12 seats that each state gets, one of them will be set aside for an elected Aboriginal,” Mr Mansell said.

Indigenous voters would be registered on a separate roll, similar to that used to elect the now defunct Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission.

To avoid “double dipping”, those Indigenous people so registered would not vote for the other, non-Indigenous-reserved Senate seats. “You either go on the general roll to vote for the other 11 senators or you vote for the Aboriginal (senator),” he said.

Some at the Uluru meeting backed the Statement but not the voice proposal, Mr Mansell said.

“Tasmania and Victoria in the meetings in the lead up to Uluru voted against the voice,” he said.

“The Tasmanian and Victorian delegates, and a lot of other people, were against the voice.

“But you had to vote for the whole document or vote against it and people didn’t want to vote against it.

“I think the (voice) referendum will have a great deal of trouble in NSW, Victoria and Tasmania.”

Mr Mansell has previously proposed Indigenous representation in Tasmania’s lower-house assembly. Premier Jeremy Rockliff said he was “cool” on the idea, believing it difficult to apply to that chamber’s multi-member voting system.

However, Mr Mansell suggested the Aboriginal community might accept dedicated seats in the state’s single-member electorate upper house Legislative Council.

“If the government … said we’ll give you two seats in the Legislative Council, I don’t think the Aboriginal community would walk away,” Mr Mansell said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout