Prison population high as crime falls

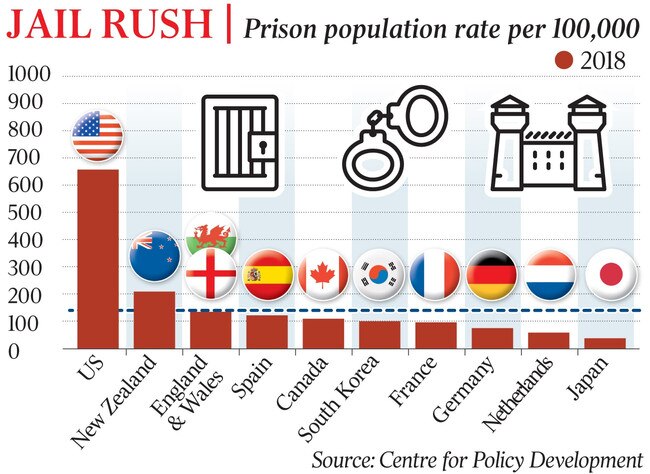

Australia imprisons people at a higher rate than at any time since Federation, requiring a burgeoning criminal justice system despite falling crime rates.

Australia imprisons people at a higher rate than at any time since Federation, requiring a burgeoning criminal justice system despite falling crime rates.

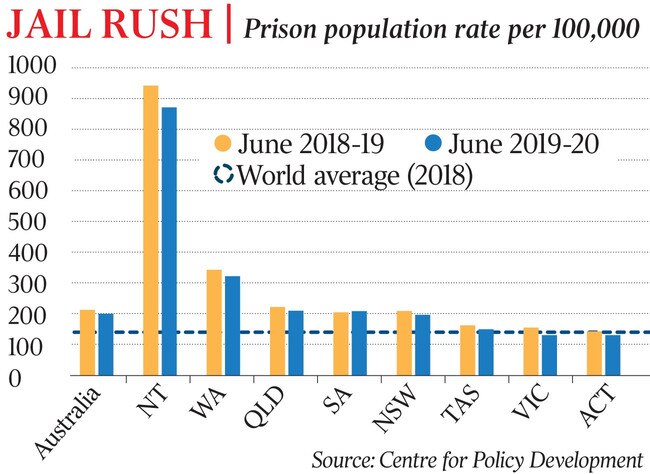

Research by the Melbourne-based Centre for Policy Development found imprisonment rates were higher than the global average in every Australian state and territory except the ACT.

The Partners in Crime report, to be published on Thursday, argues that Australia’s criminal justice system costs the taxpayer $4bn a year but steers the most disadvantaged towards, rather than away from, more offending and more jail time. Getting off the criminal justice “conveyor belt” is the exception rather than the rule: 55 per cent of prisoners return to jail within two years.

The report cites a survey of prisoners in which more than a third said they were homeless in the month before prison, but more than half expected to be homeless on release. More than half were unemployed in the 30 days before prison, yet less than a quarter had employment organised on release.

“Rising incarceration rates have been locking more and more of Australia’s most vulnerable people into cyclical and intergenerational disadvantage, at enormous and escalating costs to taxpayers with hugely negative outcomes for individuals, families and communities,” said the Centre for Policy Development’s chief executive, Travers McLeod.

The report finds a devastating impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Indigenous Australians comprised about 2 er cent of the population but accounted for 28 per cent of the adult prison population. More than half of all young people in detention were Indigenous.

“This is not about being soft on crime. We acknowledge prisons and custodial sentences are necessary to protect the public, deter crime and facilitate rehabilitation,” the report states.

“Yet Australia’s prison boom has occurred during an extended period of falling crime and the largest falls have been for the most serious offences.

“Despite this, each stage of the criminal justice conveyor belt increasingly points to jail.”

The report cites North Carolina’s Justice Reinvestment Act of 2011, which led to noticeable change within three years. The prison population fell by 8 per cent, 10 prisons were closed and an estimated $US560m in prisons spending had been saved or avoided. Over the same period, more probation officer positions were funded, more prisoners received post-release supervision and revocations of probation fell. North Carolina’s crime rate fell by 11 per cent.

“We can reform our criminal justice systems, put fewer people in jail and make Australian communities safer and healthier,” the report states.

Partners in Crime urges governments to do “community deals” that put resources where there is a concentration of disadvantaged people, ensure changes are supported by evidence and co-ordinate policy reforms to make them coherent.

In Perth, Noongar man Mervyn Eades knows the path from disadvantage to jail well. He beams when his four-year-old son, Mervyn junior, sings the alphabet. The 50-year-old community worker is determined his son will have the education and stability he did not get. Mr Eades was illiterate through primary school in the far south of Western Australia and spent his high-school years between juvenile detention and government-run children’s homes before graduating to adult prison.

He was 31 when he broke free from a cycle of jail, poverty and drug abuse that was alarmingly common among his peers. Mr Eades now helps recently released Aboriginal men find work. He is proud that 10 are currently buying their own homes. But Mr Eades said it was tragic that on prison visits he often saw the men he was in jail with as a teenager.

“Our old people had nothing to leave us because they worked for free, and we were born into poverty,” Mr Eades said.

“The consequences of that are still being felt today.”