Why work is so much better than welfare in remote communities

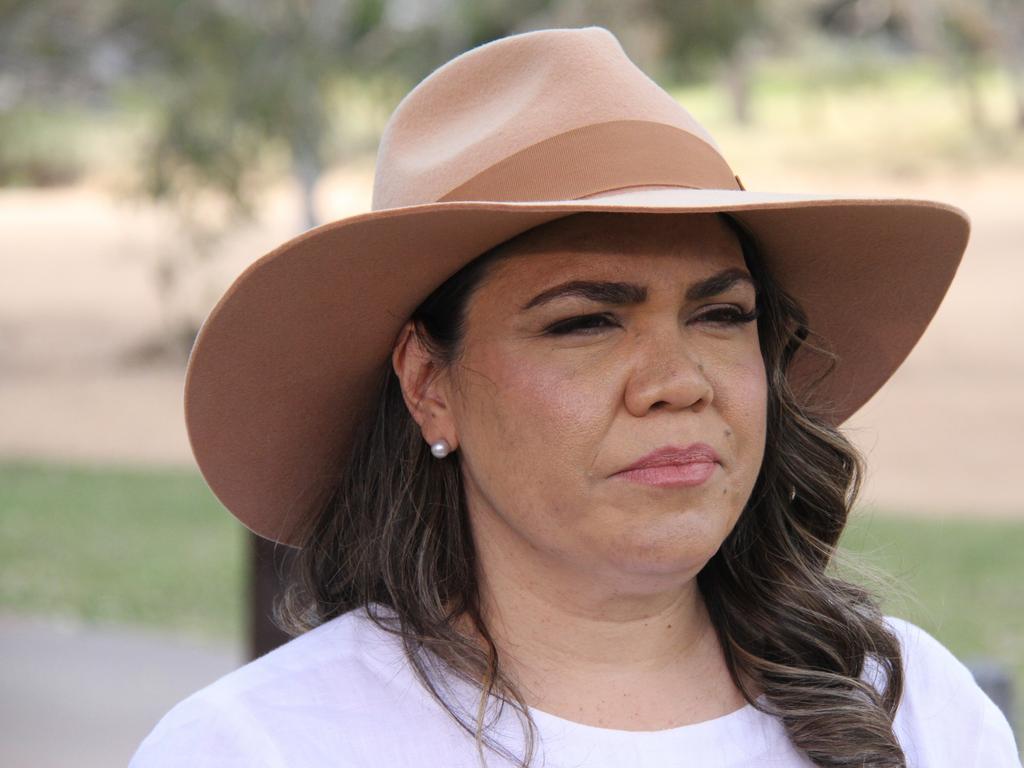

Buoyed by her own experiences under the Community Development Program, Malarndirri McCarthy is hoping to return dignity to the workplace.

A young Malarndirri McCarthy was employed at her home community of Borroloola in the work-for-the-dole scheme that both sides of politics supported for decades.

The Community Development Program, or CDEP, started small in 1977 and helped Aboriginal people establish and sustain communities in the post-mission era.

The future Indigenous Australians minister was 23 and living at home in the Northern Territory gulf country when the local Aboriginal organisation that was in charge of the CDEP program there hired her.

“I wanted to give something back. The local Aboriginal organisation employed me with some ideas and concepts I had,” Senator McCarthy told Inquirer this week.

“I was on the CDEP program and set up the first local community radio station while I was on it.

“And then that went on and I ran a training school to teach numeracy and literacy … there were four language groups, so I took two students from each on the advice of each of those language groups to show fairness so there wasn’t any conflict amongst the different groups and I taught them reading and writing (and numeracy), but also involved them in broadcasting the arts, and a couple of them went on to run the radio station and the others went on to run festivals.”

McCarthy’s good experience of the remote work-for-the-dole scheme in the 1990s is common. Back then, Indigenous community organisations received and pooled CDEP money and moved participants around from task to task as needed.

Remote communities liked the autonomy, they liked being nimble and they especially liked not having to apply for a grant each time they wanted to do something new, like run a night patrol. They had an Aboriginal workforce on hand and a reliable income that allowed them to make plans.

On the Ngaanyatjarra lands, Indigenous organisations in each of the 10 communities in the region used CDEP money to employ local Aboriginal maintenance crews, to employ additional Aboriginal education workers in classrooms, to run a community safety program helping victims of family violence, and to run the Warburton Arts Centre famous for its glass works.

McCarthy says of her time in the old work-for-the-dole scheme: “It was very busy. People had things to do. They felt proud. There was dignity in the workplace.”

Her Indigenous platform for the coming federal election is “jobs, jobs, jobs” and she says she wants to bring back the dignity of work.

First, Labor will fund 3000 remote Indigenous jobs in remote locations within three years. These will be jobs with regular working hours, proper wages, superannuation and holidays. So far, 200 Indigenous people are employed in trials of that scheme.

Others will start soon, working for employers who have been awarded grants since December.

Second, Labor intends to replace a failed iteration of the work-for-the-dole scheme that has been in place for the past 10 years.

Since 2017, successive governments have been promising to overhaul or scrap it.

Following consultations around the country, that scheme is scheduled to become a remote employment service on July 1 to “support people who are not job-ready, or who are unable to be placed in a job right away, with the skills and resources they need”.

McCarthy has been taking advice from an Indigenous working group on how that service will work.

Local Aboriginal organisations will identify work to be done in their communities such as caring for the elderly or road maintenance. There will be support and training for private enterprise.

“I absolutely see our communities across Australia thriving. I absolutely see that their potential is still untapped,” she said.

For some, the former CDEP work-for-the-dole scheme is the gold standard because it sustained remote Indigenous communities.

Sceptics including Damian McLean – shire president of the Ngaanyatjarra lands that stretch from the Rawlinson Range to the Gibson Desert – says that is what made CDEP a target.

McLean believes that conservative forces wanted to get rid of it because they hoped this would result in the closure of remote communities that were otherwise unsustainable.

However, serious thinkers in Indigenous policy had concerns about the old scheme before the Howard government began to dismantle it in 2007.

Marcia Langton, now University of Melbourne associate provost, had called the scheme a poverty trap. Cape York leader Noel Pearson said it should be redesigned “to add value to the community while never becoming an unemployment trap, including a trap for community organisations who derive most of their service funding from the program”.

The CDEP was seen as a destination rather than a stepping stone. And there was disbelief when the scheme moved to urban areas in the 1980s.

Was working part-time for below minimum wage really the only realistic option for Indigenous Australians living in the mainstream economy?

The Central Land Council’s general manager, Mischa Cartwright, told Inquirer this week: “The CDEP wasn’t perfect, but we fondly remember it as one of the biggest and most influential programs in the Aboriginal affairs portfolio. It employed many thousands and helped to grow the most successful employment sector in remote communities – Aboriginal ranger programs and art centres”.

At its peak in 2002-03, the original work-for-the-dole scheme employed a quarter of the nation’s entire Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforce: 35,200 Indigenous people in 272 communities.

When an overarching replacement for CDEP eventually came in 2015, it was called something similar – the Community Development Program, or CDP. This almost identical abbreviation, without the ‘e’, began appearing in government communications.

However, the new scheme was almost unrecognisable in practice. It was administered centrally by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, with all payments controlled by Centrelink. The commonwealth invited private companies in as employment service providers. And it introduced hard consequences for those who did not do the work.

Payments were turned off and people began to go hungry in places like Warburton where few had reliable access to a mobile phone, reliable internet or the English skills to comply with the new scheme’s reporting requirements.

As problems with the CDP made headlines in 2016, Tony Abbott told The Australian: “Abolishing CDEP was a well-intentioned mistake and CDP is our attempt to atone for it.

“I wouldn’t for a moment suggest that it (CDP) can’t be improved, but ending consequences for not turning up would be disastrous,” he added.

Meanwhile, in Warburton McLean spent untold hours on the phone to Centrelink’s Adelaide call centre helping traditional desert people get their CDP payments reinstated.

The case of then 34-year-old Aboriginal man Joshua Dawson was typical. He left his home community of Warburton to go to a funeral in Wiluna but had not sought an exemption from CDP duties. He asked McLean for help when someone on the phone at Centrelink said he must talk to a “complaints trained officer class 6 or above”.

Dawson did not understand.

“Yeah I knew what that meant, unfortunately,” McLean told Inquirer.

“You go to the participation solutions line and you get made a ‘complex participation failure’. That then morphs into more mindless gibberish and eventually you are told you need a social worker – but there is none available. I had complex participation failure cases that went on for days.”

McLean said quite a few locals left their communities on the lands for Kalgoorlie, where they could walk into a Centrelink office and literally wait for money.

These people eventually came home, he said, but often after falling into weeks or months of drinking.

When they got back to the dry communities of the Ngaanyatjarra lands, they had been registered by Centrelink as living in Kalgoorlie for the purposes of CDP and would inevitably be “breached” again for not showing up to assigned work or appointments in the goldfields city.

The abolition of the old scheme and years later the introduction of the more punitive CDP led to a big increase in poverty in remote communities, according to Francis Markham, a fellow at Australian National University’s Centre for Indigenous Policy Research.

“It wasn’t just the penalties and suspensions, or the people who found staying on Centrelink too difficult and fell through the holes in the safety net,” Markham said.

“It was that before, during the CDEP days, (Indigenous) organisations used to be able to earn money in the market using their CDEP labour force, and this meant that they could usually offer CDEP workers extra hours beyond those necessary to earn the equivalent of a social security payment.

“This meant that participants in the old scheme could earn ‘top-up’ income by working more – an average of about $100 per week. CDP meant no more top-up work and plummeting incomes.”

When the Ngaanyatjarra people went to the Federal Court in 2019 claiming the CDP was racist, the commonwealth saw the writing on the wall. It was administering a scheme designed for Indigenous Australians that had been shown to be more punitive than comparable schemes for mainly non-Indigenous Australians. Ultimately, a mediated court settlement included a $2m commonwealth grant to the Ngaanyatjarra people’s shire council for community infrastructure and arts projects and a commitment to design a better pilot project on Ngaanyatjarra lands.

That is the background to the Morrison government’s decision in May 2021 to make work optional in the CDP.

The scheme could no longer be called work for the dole. It is now simply welfare.

Due to the pandemic, the government had not been enforcing work obligations for CDP participants throughout most of 2020 and the first months of 2021. This means there has been no requirement to work in the remote work-for-the-dole scheme for five years.

Coalition Indigenous affairs spokeswoman Jacinta Nampijinpa Price says Labor should have fixed this long before now, except it was preoccupied with creating an Indigenous voice.

“The government needs to admit they put replacing the CDP on hold while they were distracted by the voice,” she said.

“The delay and inertia hurts our most marginalised the most. Ensuring there was a proper jobs and training program in place should have been a priority for this government, not a fourth quarter afterthought.”

The National Indigenous Australians Agency has told the government 15,000 of the 40,000 Aboriginal people receiving CDP payments are “job ready”, meaning they could move from welfare to work if an opportunity was identified or created.

In Central Australia, community leaders are particularly concerned about the job prospects of young Indigenous people in remote communities. Their engagement in education, training and employment is half that of their Indigenous peers in cities.

The Central Land Council, which represents 24,000 Aboriginal people from 15 language groups, is pleased that Labor is investing in 3000 jobs for Indigenous people in remote areas. It wants to see more of this.

“This is far more productive for communities and local economies than the failed CDP approach of keeping people on a treadmill of appointments, looking for non-existent remote jobs,” the council’s Mischa Cartwright said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout